The centennial issue of the journal Foreign Affairs captured the zeitgeist in its title: ‘The Age of Uncertainty’. The term ‘zeitgeist’ - a spirit of the times - emerged from the German Romantic philosophers of the 18th Century, Herder in particular, as Europe sought to grasp with its explosive metamorphosis from the old order of theology, feudality, and monarchy. Tossed in the tumultuous waves of a changing world, the concept of zeitgeist represented, at its core, a revolution of ideas.

This revolution had two related facets. There was the revolution of thought in the Enlightenment; of reason, rationality, conscience, and science, which gave birth to its centrifugal counterpart in the Romantic revolution of literature and art. And there was the revolution of social order in the birth of political systems - parliamentary democracy and republicanism - reflecting society as an association of individuals with agency and conscience, thus requiring boundaries on the roles of institutions.

Two themes appear to characterise much of anxious dialogue on the current zeitgeist. In one, we are now in a post-liberal, post-American world where the global order from 1945, characterised by multilateral institutions, internationalism, and globalisation, is an obsolete relic of the past. This view sees America’s catastrophic withdrawal from Kabul and defeat by the Taliban as the curtain call on a disastrous period of unipolar American hegemony since 1990, and a world where civil liberties have been globally declining every year for the past 15 years. Liberal democracy is fighting a rearguard action at home and abroad, and realism should attempt to established a limited order of like-minded nations, rather than seek a revived global order.

The other view acknowledges that the unipolar moment is over, that liberal democracy is in global decline, and that the post-Second World War institutional order has inherent design flaws. However, in this view Russia’s attempt to wipe Ukraine and her people from the map is evidence that the alternatives offered by Russia and China are a step back to imperialist autocracy. That the war in Ukraine is merely the most striking, compelling evidence on the back of a decade of Russian and Chinese aggression in which force is being used or threatened to change the global map. And this contrast provides a stark reminder that the pursuit, however challenging, of societies and political systems grounded in shared values of tolerance, openness, and individual rights, is a worthy struggle.

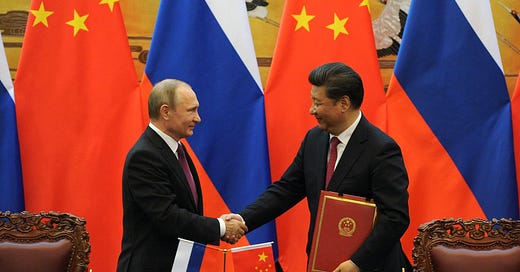

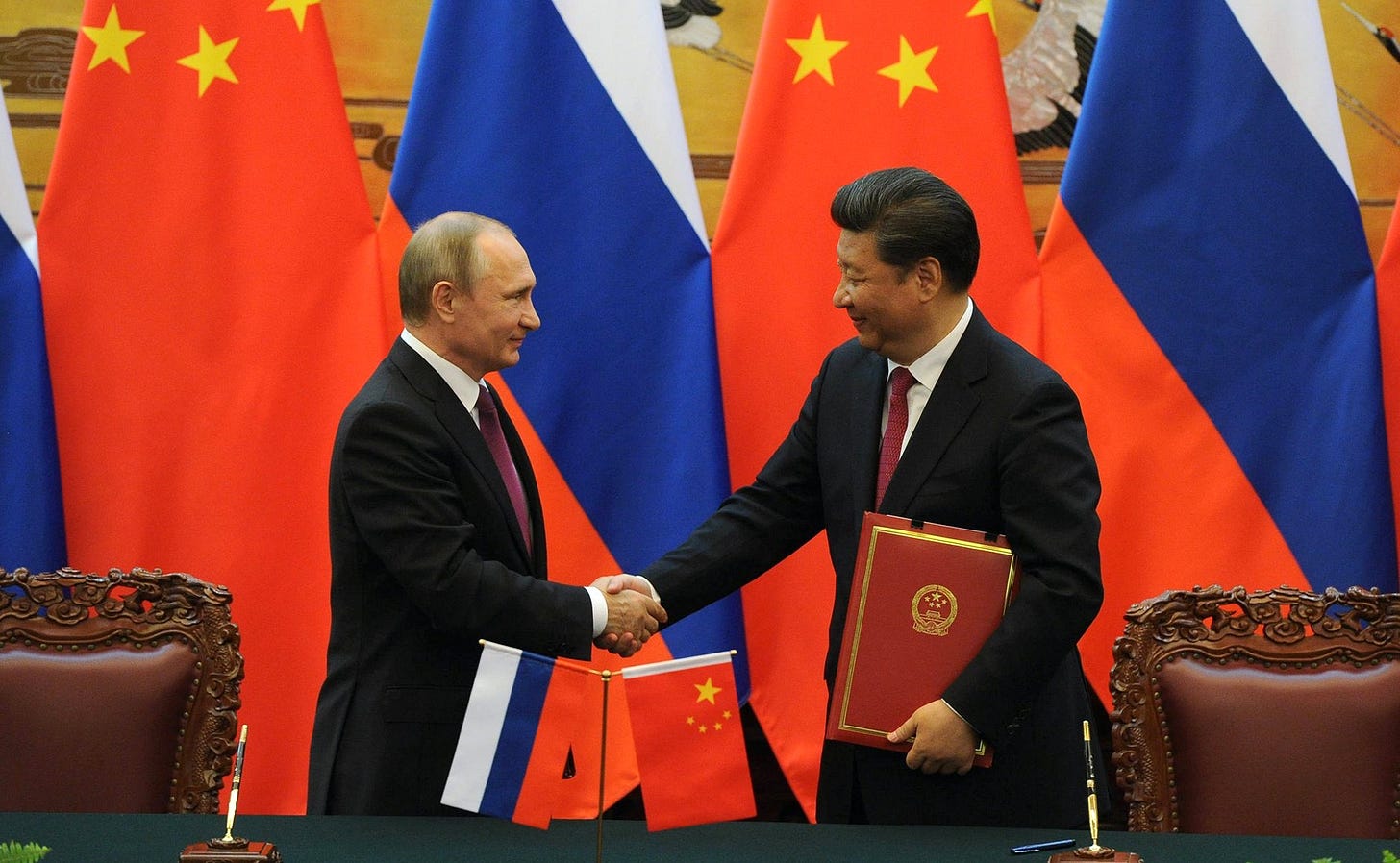

It is this latter view that is seeing with clarity. This clarity comes from the reality that for the first time since the Cold War, we have now returned to a struggle of ideas, a contest between two divergent views of how the world should work. On the 4th February last year, mere weeks before Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin issued a joint declaration that China and Russia’s partnership would have “no limits”. The Russian worldview is a project of imperialist revisionism, with Russia deeming itself entitled to “spheres of influence” in a world where the strong do as they like and the weak suffer what they must. China’s worldview increasingly reflects the ideology of Xi, a form of Marxist-Leninist nationalism, with increasingly centralised political and economic State control coupled with a weaponised nationalist foreign policy, viewed through the Marxist lens of historical determinism that sees China as the inevitable victor with history on its side. This is a battle of ideas that we didn’t see coming until these ideas erupted into overt conflict in Ukraine.

At its core, the concept broadly known as “liberal democracy” is an idea. It is powered by ideas; ideas that extend from how we conceptualise the individual to society as a whole. However, as Francis Fukuyama has written, the virtues of liberal democracy are also its most vulnerable weakness; open, diverse societies are challenging to make work. Liberal societies by definition are not tight-knit societies in a way that more homogenous societies are, particular if those societies are bound by religious and/or ethno-nationalist ties, or homogeneity is enforced through autocracy. Freedom comes with many paradoxes, not least the need for reciprocal responsibility between individuals and institutions that comprise the social order. And we now stand at a historical moment where two resurgent, revisionist powers want to offer an alternative idea to liberal democracy.

This moment arrives when we have seemingly run out of road; we have neither the faith in our systems and societies, the appetite to consider our current societies and freedoms worth struggling for, nor the vision to think about a better future to improve those systems. We have no concept of our ontological roots; we are unmoored from the historical context of our own evolution. Within the zeitgeist of our Age of Uncertainty is our own uncertainty about the viability of our societies, this imperfect project of liberal democracy. And the ongoing denigration of this project by Right/conservatives and Left/liberals alike is a dangerous game of being careless with what we are wishing for. In a zeitgeist such as ours, a reminder of our ontological roots is mission critical.

The revolution of ideas that gave birth to liberal democracy not occur in a vacuum; it required a long gestational period of history from the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Concepts of the individual as possessing innate moral equality and freedom of conscience were owed to Christian theology in the 12-14th Centuries. The very basis of secular society was derived from the theological recognition that if the individual was born with moral agency, this acknowledgement entailed consequences for the relationship between the individual and institutions of power in the Church and the State. This distinction also provided the basis for the recognition of individual natural rights, to be enshrined in law and protected by the State. This evolution in theology and philosophy was the genesis for a society where the fundamental unit was the individual, an evolution that saw the necessity for separation of Church and State, of the need for religious pluralism and tolerance, and of the necessity for separation of powers.

This radical ontological revolution in thought and society did not occur with ease; it was soaked in the bloodshed of the Reformation, the Thirty Years wars of religion, the French Revolution, the expansion of European imperialism, and two World Wars. It required a Cold War to finish the 20th Century struggle of ideologies. These organisational principles, centred around the individual, natural rights, the rule of law, secular and pluralist societies, have always required struggling, and at times in history, fighting for. And it has been imperfect, because it is a human endeavour. Modern Left-liberals who disparage “the West” emphasise, for example, that this project also included imperialism and slavery. What they refuse to see, because it undermines their own political project, is that liberal democracies have the capacity to self-correct.

No other socio-political system in history has exhibited this design feature of error-correcting capability, because several key ingredients are required: a society sufficiently open to express dissenting views from the status quo; a press free enough to disseminate those views; a judiciary independent from political power accessible to individuals to challenge political power, and adjudicate on issues against government policy if required; an economy free enough to generate progress and, if required, develop alternatives. And while the course of error-correction may be long, these design features allowed our societies to correct a crime against humanity like slavery, while in contrast the Trans-Saharan slave trade operated by Arab merchants continued long after the abolition of the Transatlantic trafficking in human life.

An understanding of our shared ontological framework for society, and of how difficult and imperfect a struggle this project has been, is crucial to acknowledging both that it will continue to be a struggle and that the reward of pluralist, open societies is worthy of that struggle. This acknowledgment is crucial because problems do abound; the threat of planetary disaster, both from the climate and other potential man-made catastrophic risks; a failed neoliberal economic model with seemingly no alternatives except doubling-down like deluded gamblers; and the erosion of our belief that the pursuit of liberal democracy is worthwhile.

Nevertheless, the rise of illiberal autocratic nations in Russia and China and should make the contrast in alternatives clear; such actors throughout history have always gambled on the inherent self-doubt of liberal democracies and our willingness to defend our ideas. To quote Timothy Snyder, for 30 years we have taken for granted:

“that democracy was something that someone else did—or rather, that something else did: history by ending, alternatives by disappearing, capitalism by some inexplicable magic...But democracy demands “earnest struggle,” as the American abolitionist Frederick Douglass said. Ukrainian resistance to what appeared to be overwhelming force reminded the world that democracy is not about accepting the apparent verdict of history. It is about making history; striving toward human values despite the weight of empire, oligarchy, and propaganda; and, in so doing, revealing previously unseen possibilities.”

If liberal democracy is, at its core, an idea that requires earnest struggle, then we need conservatives and liberals alike to start producing ideas again. Snyder’s point about liberal democracy being something that “something else did” is a comment on the post-Cold War order, where the hubris of the disintegration of the Soviet Union created an incurious, incubated echo-chamber of Western thought that assumed that the emergence of liberal democracy in conjunction with free markets had become an inevitability. Ironically for the fact that this school of thought was dominated by centre-Right thinking, this was in fact a very Marxist view of historical determinism. This period also holds another bloodstained lesson for the future liberal democracy; that ideas can also be dangerous in the absence of checks and balances, because those ideas can easily morph into ideology; hubris into nemesis.

The neoconservative movement in America serves us that lesson; the certitude and arrogance that conceived of itself as riding on an inevitable wave of history, Bible in one hand and Marine Corps in the other, the vanguard of good and democracy in a dichotomised world of evil and enemies. The world suffered, America continues to suffer, and liberal democracy served up the perfect example of hypocrisy for illiberal actors to mobilise in their favour. No doubt, hypocritical conduct such as the invasion of Iraq and the Bush-Obama torture program have undermined any moral claims of legitimacy. These should be fully addressed and acknowledged in the context of the capacity of liberal democracies to self-correct. But let us be clear about the difference: liberal democracies can self-correct; Russia and China have no such capacities, meaning their destinies are implosion, revolution, or inexorable decline.

Nevertheless, at the very least conservatism appears to be willing to learn from its foreign policy mistakes, and even acknowledge that free market fundamentalism needs a rethink. Left-liberals, however, remain mired in a view of foreign policy that amounts to little more than “the ‘anti-imperlialism’ of idiots”. This ‘anti-imperialism’ of idiots views imperialism as a purely “Western” pathology, attributable only to the U.S. and former imperial powers like the UK. As a result, ‘anti-imperial’ idiots gave their support to Assad’s murderous regime in Syria, blamed NATO expansion for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and excuse Iran’s militant path as an justifiable response to U.S. power.

Because many Leftists view politics as an expression of personal morality, details are secondary; this naivety leads them to support hideous regimes and ideas because they see the world in terms of moral polarity, in which “the West” is always bad. Ironically for a movement that sees itself are inclusive and representative, its concept of “the West” always excludes democracies like South Korea and Taiwan, crucial to the maintenance of an international bulwark of liberal democracy, and views “imperialism” only, to quote Leila Al-Shami, “...through the prism of what it means for westerners – only white men have the power to make history.”

Thus, we need some renewed vigour in our ideas of ourselves, of liberal democracy and its promise. Centre-Right conservatism needs to cast off its post-Cold War hubris and avoid the temptation of retrenchment and isolation against the rising illiberal tide; Left-liberalism needs to jettison the anti-imperial idiots and realise that liberal democracy provides the best opportunity for a more just society, and that at some point action is required rather than theorising and pontificating. The uncomfortable reality for both movements is that intervention may be necessary in order to counter powers like Russia and China, who will operate on the basis that might makes right. And others may follow; consider that at a vote in April 2022 to expel Russia from the UN Human Rights Council, 24 countries, primarily from the Global South, voted against the resolution. Russia provides more than half of the military arms to Africa, while China extends its reach and influence in economic terms through the Belt and Road Initiative. Consider also that in 2020, China issued a list of 14 demands to the Australian government that included Australia remaining silent on China's human rights abuses.

This is the rising illiberal world order. Of course, there is a signal of optimism in the noise of illiberalism. Australia rebuked China, and there has been an increase in limited multilateral cooperation in Asia between South Korea, Japan, Australia, India, and the U.S., aimed at curbing China’s aggression and expansion. And it is the small democracies of Eastern Europe and Scandinavia that have shamed the lynchpin of Europe, Germany, into eventually agreeing to provide Leopard II tanks to Ukraine. Of course, Ukraine has also demonstrated in no uncertain terms why we need America, because as Robert Kagan has said, we are part of a never-ending power struggle, whether we like it or not. That struggle is, once again, a struggle of ideas, of competing views of how the world should work. On offer is revisionist imperial expansion and the denigration of human rights, dignity, and life, proudly brought to you by the Sino-Russian worldview. We should remind ourselves of the ontological roots of liberal democracy, and how despite its flaws, the in-built error-correcting capacity means that we, at least, have a chance to calibrate the system toward a more just social order.

Few are able to express the complexity of world while fairly criticising "left" and "right" political perspectives.

So well put.. Feels like I could, and should, share this, over and over again..