In the aftermath of the 2016 election of Donald Trump as president, the Washington Post adopted the slogan, “Democracy Dies in Darkness.” While evocative and somewhat quaint, it is historically illiterate.

The Rise and Progressive Decline of Democracy

Democracies are not born in darkness, nor do they die in darkness. While democracy in a country like the UK or US may trace a longer lineage, democracy in many European countries was born, extinguished, and reborn between successive World Wars in the 20th Century. This was full catastrophe democratic emergence, for which living memory is sadly now scarce.

But many alive today would remember the “third wave” of democratic emergence which swept through Spain, Portugal, and Greece, during the 1970's, Latin America in the 1980's, and Eastern Europe in the 1990's. In the former East Germany, the ‘Monday Demonstrations’ drew hundreds of thousands into the streets chanting “Wir sind das Volk!” (“We are the people!”). The Polish trade union, Solidarity, became a movement which drove the end of Communism in Poland, through mass civil resistance and protest.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of the Soviet Union gave birth to what policy analysts came to term the “unipolar moment”, with the United States as the only standing global economic and military superpower. Some, in particular Francis Fukayama, infamously declared that we had arrived at the “end of history”, a delusion that the combination of democracy and free market economics were now the only game in town. Fukayama et al. have had the epistemic humility to recognise that their analysis at the time was shortsighted. But then again, hindsight is always a wonderful benefactor to the lens of history.

Barely 30 years after the emergence of democracy in Poland, the Law and Justice (PiS) party has strangled democratic function, removed independent electoral oversight, breachedseparation of powers to meddle with the judiciary, taken over control of the media, centralised power, choked off potential challenge from other parties, and espouses a poisonous, religiously-motivated rhetoric in relation to race, immigration, and sexual orientation. They could have taken inspiration for all of this from the Republican Party in the US.

Unlike the “third wave” of democracy, the more recent attempts at democratic emergence have not born fruit. The Arab Spring, for all its promise, ended in a winter of increasingly intolerant regimes, repressions, and violence. Democracy has been extinguished in Hong Kong only 23 years after “one country, two systems” began, in a haze of rubber bullets, tear gas, and a brand new security law already in action to dismantle pro-democracy media and arrest would-be dissenters. None of this happened in darkness. It happened in full view, with no one paying attention, distracted no doubt by some furious outrage at J.K Rowling, and with the so-called “international community” rendered as the impotent vessel of empty rhetoric that it is.

Democratic Backsliding

The term “democratic backsliding” has become the euphemism for the process of state-led dismantling, erosion, or elimination, of the institutions and systems which sustain existing democracy. It is crucial to note within the definition that this is a state-led process, where the very institutions of democracy are the channels through which important aspects of democratic function are attacked and eroded. This concept may also be referred to as ‘autocratisation’, i.e., the reverse of democratisation, characterised by a decline of various aspects of democratic function.

Before considering the characteristics of democratic backsliding, however, it is important to consider the characteristics of democracy itself. Unfortunately, for most of our generation, “democracy” simply means having a vote to use (or not, for those under 30) in an election. But a democracy is not merely defined by having elections. If it was, Belarus would be considered a ‘democracy’. The following figure is from the 2018 report by Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), the largest global database of democratic indictors, and succinctly illustrates the various components of democracy.

While this figure provides a neat synopsis of the core aspects of a full and free democracy, it is important to note that any number of indicators may fall within these concepts. As a non-exhaustive list, for example, these may include:

The independent oversight and implementation of electoral laws and frameworks;

The right to organise in different political bodies and parties;

A system which does not place barriers in the way of any such body or party competing in the political arena;

Full extension of the franchise to specific population groups (in particular women, minority ethnic groups, and groups defined by sexual orientation);

Safeguards against corruption;

The executive operating with openness and transparency;

Free and independent media;

Academic freedom with academic institutions from from indoctrinating ideologies;

Freedom of assembly and the right to protest;

An independent judiciary;

Personal autonomy;

Political inclusion irrespective of socio-economic status.

On the right-hand side under ‘Liberal Component Index’, constraints on the executive by the judiciary and legislature represents a concept known as “separation of powers”, where the main institutions of state - the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary - retain independence from each other. As a crude definition, the legislature holds the power to make new law and change existing law; the executive (i.e., the elected government) holds the power to implement law and decide on policy (domestic and foreign); and the judiciary holds the power to apply the law and make judgments in relation to the law and, of particular importance, provide access for citizens to dispute government actions.

Thus, the executive is responsible to the legislature (e.g., executive acts may require approval from Parliament) and accountable to the judiciary (which may find acts of the executive to be illegal, or in breach of a constitution if the country has one). Parliament in the UK is the legislature, and the government as the executive is expected to govern within limits placed on it by Parliament and the judiciary. Where the government exceeds its legal boundaries, the judiciary may provide a remedy.

To hammer this point home: having elections does not a democracy make. The integrity of these other core aspects of democracy is required to make elections meaningful. In the absence of integrity in these characteristics, merely casting a ballot in a box may amount to little more than a Pyrrhic act for citizens.

Characteristics of Democratic Backsliding

Democratic backsliding appears to have a number of characteristics, and different scholars may emphasise the relative importance of particular factors. Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman have emphasised the process of the democratically elected executive beginning to undermine the integrity of the electoral process, evade checks on executive power, particularly from the judiciary and legislature, and restrict civil liberties and rights.

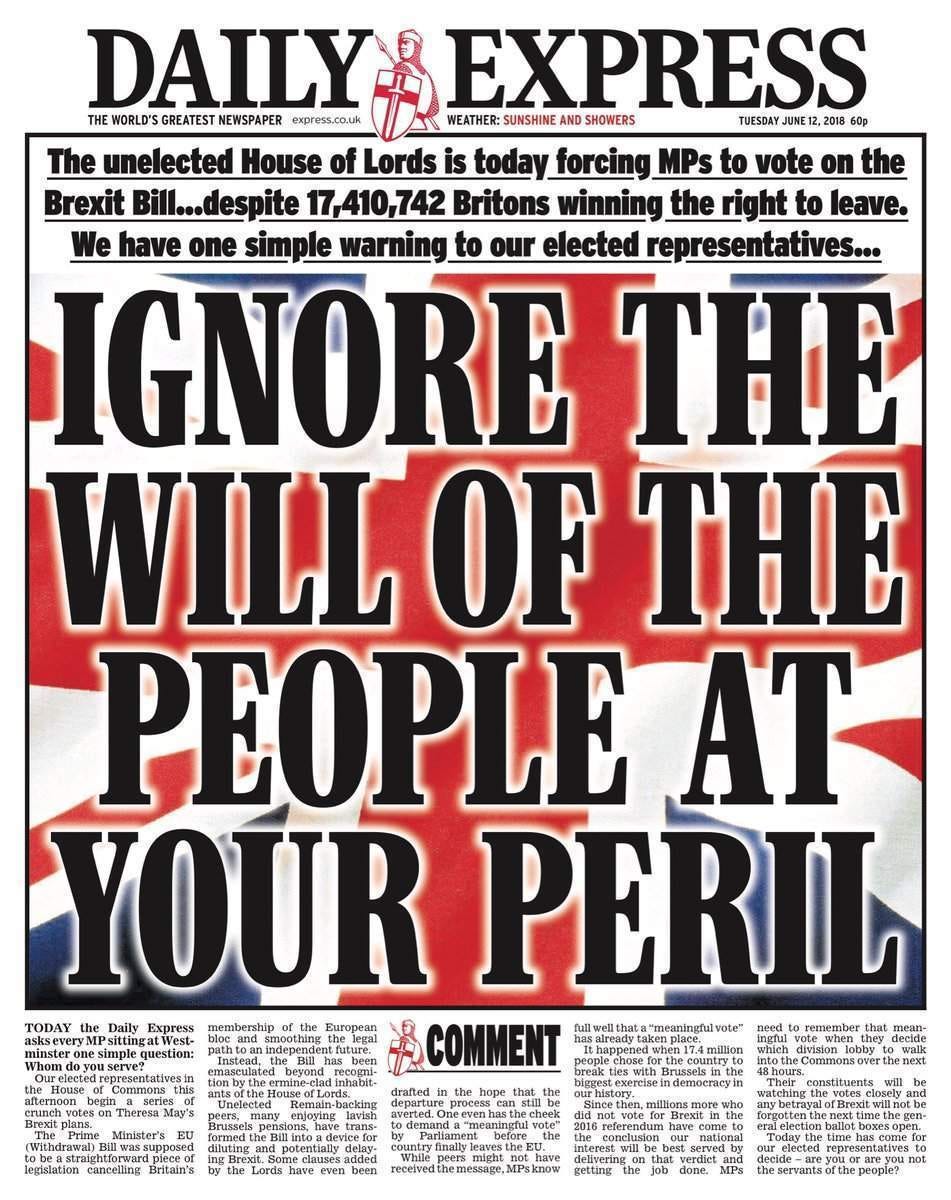

To generate acquiescence for such autocratic manoeuvres, the executive stokes partisan tensions and evokes an “Us vs. Them” rhetoric, claiming to speak on behalf of the opaquely-defined “real people”. The latter is often deployed to justify attacking the other institutions of state, and lay blame on the equally opaque “elites” (a darling buzzword of the right-wing UK media), often the legislature and judiciary, who stand in the way of the “will of the people”.

Pippa Norris has argued that these processes, while correct, focuses solely on “supply-side” factors and ignores “demand-side” factors, in particular the role of the electorate, and of institutional factors. While elections to do not make a democracy, they remain an expression of the electorate, and Norris and others have argued that there are sections of the electorate who want more authoritarian rule. Indeed, there is evidence for this from both the US and the UK, with political scientists describing a concept termed “collective narcissism”, a form of in-group bias which champions a sense of national importance and identification, that their nation is deserving of respect and is not given its due by others, and a rejection of perceived out-groups. Thus, slogans like “Make America Great Again” during the 2016 presidential race, or “Take Back Control” during the Brexit Leave campaign, appeal to collective narcissism.

But the analysis of Norris and others is a distinctly liberal, arrogant slant which barely conceals the “old White male” stereotype voter. It ignores what economist Mark Blyth and political scientist Eric Lonergan documented brilliantly in their book, Angrynomics, that while people turning to populist parties with authoritarian impulses is an expression of anger, this anger is justified. While concepts like collective narcissism may explain some of the electoral impulse toward autocratic parties, it is disingenuous to point to the election of authoritarian populists as solely a reflection of want. There are fundamental basics required for citizens to participate in a functioning democracy: education, healthcare, adequate housing, food security, financial security, and safety. When citizens have these requirements underfunded, eroded, and removed, which has been the modus operandi for the Right for 30yrs, the resulting anger is justified. The anger of huge swathes of the electorate now also reflects over a decade of being battered by austerity, facing declining life expectancies, a demolished healthcare system, a failing education system, declining real wages, and increasing cost of living. And then, to add pure insult to neoliberal injury, to be told: your lot is your fault, your responsibility.

Binyamin Applebaum has highlighted that the erosion of democracy is not independent of economics: they are related. For parties like the Tories or the Republicans, free market evangelism is the bedrock of their political identity, with socio-economic views shaped around that core gospel. But left unchecked, markets produce inequitable outcomes, which are then exploited by these same parties to foster anger and resentment among the electorate. Faced with either restricting markets or preserving stability and democratic function, the Right sacrifices democracy. And a proportion of the electorate are willing to go along with these sacrifices because for 30yrs they have repeatedly been fed a lie: that a free market equates to personal freedom.

This is the greatest false equivalence fallacy any political party ever sold to an electorate, with the effect of subordinating true individual freedoms, i.e., political freedoms, to economic freedoms. When the justified anger and discontent of those whom this system abuses and discards in society rises, the Right is there, waiting to capitalise to electoral victory with a perfectly crafted, battle-tested rhetoric. The Right reaps what the Right sows. Meanwhile, the Left is shouting at statues. This is not being glib: the evidence from Brexit, both 2016 and 2020 elections, and indeed the recent Virginia gubernatorial elections, reinforces the futility of unpopular slogans when they do not reflect public opinion. The righteous arrogance of the Left makes them tone deaf to this fact. The Right are good at mobilising the anger they have created to further their own ends; the Left are good at making those people who are justifiably angry feel like morally inferior pieces of shit. It is abundantly clear which is more effective for actually winning elections.

However, of the “demand-side” forces, institutional factors may be particularly relevant. Countries with majoritarian institutions are reliant on a stable spectrum between political Left and Right, and a commitment to the democratic process. In such conditions, like in the UK in the post-World War 2 period, administrations may change hands over and over and while the country may experience instability, economically or even socially, democratic function remains stable. However, political scientist Arend Lijphart argued that countries with majoritarian institutions were vulnerable if the society was deeply divided along socio-cultural lines. In such a circumstance, majoritarian systems become unstable as the institutions become targets for party power-grabs. As Norris has pointed out, countries at most risk of democratic backsliding are those with societies and political parties divided along liberal-conservative lines over cultural values (the so-called “culture wars”), and in which the democratic institutions of state cannot withstand the instability created by the divisions.

Let’s distill this into some common characteristics of democratic backsliding, accounting for the various perspectives of different commentators:

A democratically elected executive begins eroding confidence in other institutions of state, and undermines the electoral process;

The executive seeks to dismantle horizontal checks on its exercise of power from the legislature and judiciary;

The executive seeks to dismantle vertical checks on its exercise of power from other political challengers;

The executive seeks to dismantle political organisation, protest, and dissent;

The party plays to populism, fostering an “Us vs. Them” environment, and using this hostile climate to facilitate the curtailment of civil rights and individual liberties;

The party blames externalities (“the elites”, “immigrants”) for socio-economic hardships in the population (which hardships are primarily the result of Right-wing economic policies in the first instance);

The executive avoids transparency and openness;

The existing systems and institutions of state may provide channels to leverage control of institutions and consolidate power;

The party, and with a complicit media, indulge in “culture wars” as the perfect smoke-screen to keep the Left tied down debating absurdities, outside of politics.

Of the major Western countries, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) report places the US in democratic backsliding, joining Brazil, India, Poland, Hungary, Serbia, among others. The UK is not on that list, yet.

Autocratic Impulses in the British Conservative Party

So let's talk about the UK. The ruling Conservative Party has held power since 2010, but it is over the course of the Brexit debacle that the authoritarian, far-right impulses within the Tories have been released. Brexit provided the perfect scenario to stoke “Us vs. Them” fear-mongering and foster the narrative the the Tories spoke for “the real people”. This rhetoric was deployed to begin attacking institutions of state, in particular the independent judiciary. After a completely uncontroversial and constitutionally correct legal decision, the Supreme Court was labeled by the right-wing Daily Mail as the “enemies of the people”. The Court had not, in fact, “defied” voters at all, but had correctly stated basic separation of powers, that the government would need the approval of Parliament to invoke Article 50 and trigger withdrawal from the European Union.

Brexit also provided the first glimpse that the majoritarian system in the UK could, as Lijphart predicted, be vulnerable to divisions in society. Brexit was a 51.9% to 48.1% vote, hardly an overwhelming mandate from 17,410,742 Leave votes vs. 16,141,241 Remain votes. Yet the majoritarianism that emerged from this vote generated an ends-by-all-means approach to the outcome of the referendum, and in a majoritarian electoral system the Tories demolished all challenges, eviscerated Labour, and secured an overwhelming majority in the 2019 general election.

2020 is where the autocratic Tory leopard revealed its spots. In blatant disregard of the importance of openness and transparency from the executive branch to a functioning democracy, we discovered that the Cabinet Office had established a unit known as the ‘Clearing House’, which vetted Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, and blacklisted journalists from making FOI requests. We learned that only 41% of FOI requests to government were granted in 2020. We saw contempt for separation of powers and the rule of law, when a Court order for the government to comply with a FOI request resulted in the government ignoring the order, and never releasing the information.

We saw further contempt for the separation of powers when Boris Johnson prorogued parliament, suspending it for 5-weeks without justification. When the Supreme Court also ruled that this was unconstitutional, the executive again mounted attacks on the judiciary and framed it as the Supreme Court interfering with the timelines for Brexit (it was not decided in relation to Brexit, but in relation to whether the decision to prorogue Parliament had reasonable cause).

We've seen how safeguards against corruption have been swept aside, as the government awarded lucrative contracts for Covid-19 related tenders on a ‘mates first’ basis, often to firms with no relevant experience, and often to companies with which the ministers themselves were connected. Estimates put the value of these contracts up around £22-billion.

And now the quartet of bills before Parliament threatens electoral integrity, civil rights and liberties, barriers to potential political activism and competition, and threats to judicial oversight of executive power. One of these bills has already passed, the Nationality and Borders Bill. This Bill puts up to 6-million British citizens at risk of the government revoking their citizenship without notice. While we were busy passing memes about No.10 Christmas parties, the Tories were busy passing legislation that provides the executive with the means to curtail individual rights and liberties. This provides a coercive power to government to wield over citizens who happen to not be of 100% prime Anglo-Saxon stock.

The Judicial Review and Courts Bill also looms large, grounded in the government establishing the ‘Constitution, Democracy and Rights Commission’ with a view to limiting judicial review. To those of you unfamiliar with the term ‘judicial review’, and why it is an integral aspect of a functioning democracy, judicial review provides a means by which the judiciary can ensure that the government acts within the boundaries of the law, as enacted by the legislature (remember, separation of powers). Importantly, judicial review provides a right of access to the Courts for citizens, and private citizens may seek judicial review of government decisions. Under judicial review, a number of remedies are open to the Court to award a successful complainant. The Judicial Review and Courts Bill primarily targets those remedies, seeking to limit the ability of the Courts to make what are known as ‘quashing orders’, where a decision of the government or a public body is quashed by the Court. The Judicial Review and Courts Bill would allow the government to delay a quashing order becoming effective, and could prevent quashing orders applying where a complainant has already been affected by an unlawful decision (e.g., “tough luck”).

The Judicial Review and Courts Bill also bears some relationship to the now-passed Nationality and Borders Bill, as provisions in the Judicial Review and Courts Bill seek to prevent individuals from challenging, by way of judicial review, decisions in relation to asylum and immigration status. A situation could occur, therefore, where an individual is stripped of their citizenship without any notice to them under the Borders Bill, deported from the UK, and is left with no means of challenging the decision in a judicial review.

What about electoral integrity? The Conservative Party have set their crosshairs on independent electoral oversight in the Elections Bill. Compulsory voting ID has drawn most of the attention here, but when implemented properly, i.e., where the state provides the ID for individuals as occurred in Northern Ireland, this does not appear to be too much of a worry. The real worry is in the provisions for government encroachment into the independent Electoral Commission, which would be brought under the control of government ministers. This is beyond the pale of acceptable democratic norms. The proposals under this Bill include setting the parameters within which the Commission is to operate, and provides ministers with the power to remove organisations listed as political bodies, for example trade unions or activist groups. In effect, these provisions provide the ability for the executive to ban and silence organisations that it does not agree with. It would prevent smaller political groups obtaining support from larger political parties, and the emergence of new organisations or parties, essentially seeking to choke off vertical challenges to executive power.

And finally, the coup de grace, to ensure that whatever ire you feel toward the government never sees the light of day, or if it does you'll see 51-weeks to up to a decade in a prison cell: the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. A bill which defines a “protest-related offence” as anything an individual did in the past five years which could have been an activity causing “serious disruption”, itself defined in the broadest of terms. The police can enforce restrictions on where individuals can go, who they can meet, and the Bill introduces “suspicions-less” stop-and-search provisions, meaning the fundamental principle of reasonable cause is thrown out the window. People of colour in the UK know what this means for a police force with as much of a racist element as their US counterparts, only more inclined to use tasers than guns. The right to restrict and control protest, to restrict and control movement of individuals, and to stop-and-search with no reasonable suspision, are major encroachments into the fundamental rights of assembly, of organisational rights and freedom of association. In a functioning democracy and open society, these rights need to be free of fear of surveillance, interference, and retribution, or they are not rights of the public at all.

So you have to ask yourself, on the basis of what need are such laws required? Does the executive not have more pressing concerns, like a pandemic, hungry children, underfunded schools, a crumbling healthcare system, declining life expectancy, and Victorian levels of poverty? What purpose could any of these measures really serve?

The answer is that there is a difference between holding office and holding power. In a functioning democracy, a party holds office for a period of time, and, in the truly Popperian sense of why democracies are the least-worst system, may be removed through the ballot box without recourse to bullets. There is a broad consensus that holding office is a privilege, to govern on behalf of the citizens of the country, and to put good governance and the integrity of the office over the wielding of power. That consensus, upon which the integrity of the UK's majoritarian system was predicated, is gone. The Conservative Party set it on fire in the post-Brexit clusterfuck, and awoke to find that there was no functioning, viable opposition.

Since the 1980's, resumed with vigour since 2010, the Conservative Party have unleashed the most feral, barbaric socio-economic doctrine on society, and it has come to roost. The level of anger and despair in English society is palpable. And when the already desperate state of inequality blows over in public, the party will have the ability to crush dissent, silence protest, deport anyone fitting the criteria, and stick two-fingers up at the judiciary. To cement authoritarian power, the Tory party is moving to choke off both horizontal limits on their power by the legislature and judiciary, and vertical challenges from other parties and political organisations. And the conduct of the Tory party during Covid-19 gives us an inidication as to why it wants power rather than responsibly holding office: because when with concentrated power comes the ability to concentrate wealth and resources. Having the firmest grip on power will allow the Tories and their cadres to skim the cream off society and leave the rest scrapping for drops of milk. This is political subjugation for the economic gain of the minority. Democracy is being sacrificed at the alter of privatisation and backhand contracts.

The problem, as political scientist Yascha Mounk has argued, isn't just that certain democracies and their institutions are weak, it's that authoritarian regimes are strong. And the prevailing institutions, both national and international, have proven ineffectual at stemming backsliding. The remaining hope is, of course, the possibility of electoral defeat for the ruling party. But that requires votes, and obtaining those votes will require liberals to pull their head out of their gender-neutral assess and start communicating to people who have justified anger at their lot in society, without sneering at them as antiquated bigots. This is the endgame for the Left abandoning the working class. And since there is little chance of the Left fostering a unifying, class-based analysis over its current predilection for atomising society into component identity parts, because this arrogance is also its blinding ignorance, the more likely outcome is Conservative Party rule for the better part of a generation. Democracy functions on the basis of viable options that offer a legitimate alternative to the electorate. Unfortunately for the UK, that opposition is nowhere in sight.