How Can We Reimagine a Better Future?

British politics is crippled by its pathological view of class.

In 1834, the British parliament enacted the Poor Law, which placed the worldview of society deeply embedded in the psyche of the British ruling class on a statutory footing: that of the “undeserving poor”. The unwritten assumption on the other shoe, of course, was that those born into generational wealth were deserving of all that came way their way by virtue of birthright.

This view of society is a major pathology in British society and politics, permeating through her institutions, metastasising since the Victorian era. During very brief periods, all now confined to history books, certain interventions have been effective in achieving remission, if only for a brief intermission before the malignancy would return with interest.

Whether it is at its most malignant now is certainly a proposition with which millions of families throughout Britain would no doubt agree, because “the Victorians in poverty had it way worse than you"“ is scant consolation today, in a country where UNICEF are required to intervene to ensure children eat. With the Conservative Party's views on regulation, they'll probably have kids back up chimneys if the nippers will do it for less than minimum wage.

What makes Britain’s classism more brutal than other countries, the U.S. excepted, is that it goes beyond social division; it has always been rooted in the assumption of “deserving”, providing a justification for the ruling class to inflict vicious policies without conscience. And when the apparatus of State in the expansion of Empire was built upon an assumption that the upper classes constituted a breed of Anglo-Saxon Übermensch, it should hardly be surprising that the Tory relics of that age who currently hold seats in Westminster have embraced a toxic combination of pseudo-imperialism and classist cruelty.

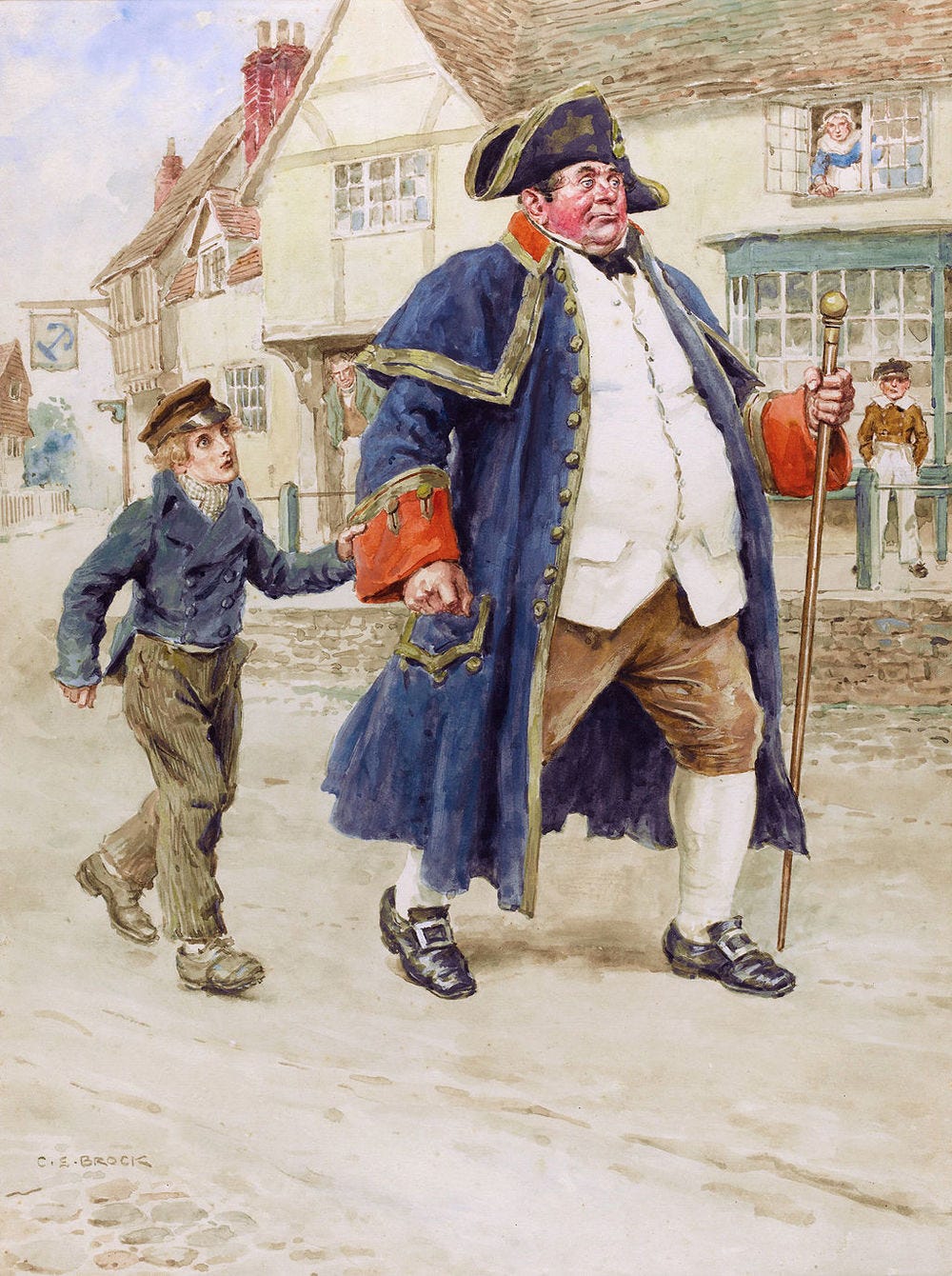

In a 2014 paper by Oxford's Matthew Lakin on the “New New Right” (NNR), the designation for the 2010 generation of Tories and their ideology - in particular, Elizabeth Truss, Priti Patel, Dominic Raab, Kwasi Kwarteng, and Chris Skidmore, as co-authors of ‘Britannia Unchained’ - Lakin stated that the NNR “want to move British society forward to the past.” And the past is bleak. There is a reason why terms like ‘Victorian’ or ‘Dickensian’ are deployed as euphemisms for poverty.

Before the First World War, poverty created such levels of malnutrition in Britain that between 40-60% of recruits during the Boer Wars were turned down as physically unfit for service. In fact, the origins of concern for the public health in the early 20th Century had little to do with a moral duty of care to society, and had more of a eugenic origin; the Anglo-Saxon Übermensch destined to rule the world could hardly be in such a state of physical degeneration if the Empire was to be maintained.

During the interwar years, the so-called “hunger marches” stepped up in earnest; men and women from working class towns would march to London to protest unemployment and poverty before parliament. The Jarrow Crusade is one such example that went down in lore, as 200 men who had recently been rendered unemployed after the closure of the Jarrow’s shipyard, the main employer to the town, marched to London from Tyneside to present a petition to parliament. The House of Commons barely debated their petition.

The 1920’s and 1930’s were periods of mass unemployment and poverty; the latter decade was also the period where Britain first dabbled with the policy of austerity. The economist Mark Blyth of Harvard, who has exposed the failure of austerity as an economic policy, argues that austerity was a major economic catalyst toward the Second World War through the hopelessness and anger it generated in European countries through the 1930’s following the 1929 Wall Street Crash. To quote Blyth:

“It took Keynes' General Theory, combined with the repeated failures of austerity to salvage slumping economies during the 1930s, to kill austerity as a respectable idea. Why, then, did it come back with such force more than 60 years later?”

Why it has come back in the UK is because it is the policy option that comes most naturally to the NNR, the embrace of neo-Thatcherite classist cruelty meshed with Victorian ideals of the “underserving poor”. To quote Lakin on the NNR:

“The NNR supports the ‘austerity programme’ of the Osborne Treasury not only in order to maintain market confidence, cut public expenditure, bring down the deficit and ensure Britain ‘lives within its means’, but to restore the conditions where neoliberal ideas can thrive. Austerity is decontested as a ‘virtuous necessity’".

In a 2017 paper by Simon Glaze & Ben Richardson of the University of Warwick, the authors highlighted several quotes from Conservative Party ideologues which lay this all bare. Let’s start with former Prime Minister and Old Etonian David Cameron:

“Of course, circumstances – where you are born, your neighbourhood, your school, and the choices your parents make – have a huge impact. But social problems are often the consequence of the choices that people make.”

One wonders whether Cameron considered that the mere accident of his birth and schooling is the only reason he became Prime Minister? Because it certainly wasn't competence. But I digress, let’s go to former Conservative Party MP Edwina Currie for her learned opinion that people in poverty":

“never learn to manage and the moment they’ve got a bit of spare cash they’re off getting another tattoo.”

Or to Michael Gove, then Education Secretary, positing that if people in poverty lacked money for food or school uniforms, then it was:

“the result of decisions that they have taken which mean they are not best able to manage their finances.”

Or this erudite statement from Baroness Jenkin of Kennington:

“Poor people don’t know how to cook.”

One presumes the Baroness cooks for herself daily.

These views have been amplified and reinforced throughout the middle-class Right-wing media, like The Spectator (the Daily Mail for public schoolboys). Rod Liddle mused in 2014:

“Why are there so many fat people in pictures of food banks? If you’re going to take advantage of a food bank, at least have the good grace to look a bit peckish and skeletal.”

It would diminish this line of thinking to describe it as merely a political ideology. It is a pathology. One which is not unique to the post-2010 Tory party, but an embedded aspect of the British national psyche.

In his examination of the NNR, Lakin highlights an instructive sentence from Britannia Unchained:

“the last thirty years of public debate in Britain has been dominated by left-wing thinking”.

This is a laughable proposition given the Tories have been in power for all but 12yrs since 1980, New Labour had its neoliberal inclinations economically, and brought the country to war illegally in lockstep with the U.S. Right-wing.

But this is actually a crucial point to understand the policy choices of the current Tory party: the modern ilk of reprobate Tory hardliners believe that the Thatcherite revolution failed. And they are the torchbearers, here to see it home in full, inflicting despair on a population while they privatise anything in sight and cream off the proceeds.

The lie at the core of Thatcherite economics, and of austerity as a policy, is that a country can cut its way to prosperity. But when this assumption is made in a society with a ruling class historically hardwired to view the working class and people in poverty as feckless and undeserving, then it should never be surprising when the policies devised by millionaires and people from generational wealth deliberately target those cuts at the very people in society who have already taken a battering at the brunt of the unprincipled policy of austerity since 2010. This is punching down, as only Etonians and City bankers know how.

The issue is that this concept of “underserving” extends far beyond poverty. In fact, sometimes the term ‘poverty’ itself is unhelpful in that it can conceptualise the issue as purely one of the income of a given individual or family. But the Tory assault on human dignity in the society they lord over extends to anyone with children, a single parent, anyone with mental health problems, disabilities, or a Fitzpatrick skin phototype of IV or over.

But this is also Britain under the Conservative Party in 2022; unprincipled, unscrupulous, corrupt, lacking any discernible ethics or moral compass. And crucially, lacking any legitimate alternative or opposition. It is a grim forecast. Sunak’s entire recent mini-budget was yet another example that post-1980 Right-wing economic thinking is devoid of imagination, intelligence, evidence, or ethics.

One brief period of optimism was born as the Second World War raged. In 1942, Sir William Beveridge published his report entitled ‘Social Insurance and Allied Services’, which simply became known as the ‘Beveridge Report’. The report was an imagination of the future, of what post-war Britain could look like with a commitment to the welfare of society that had been neglected in the pre-war years. Beveridge identified five “Great Evils” - Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness - that afflicted the welfare of society.

Three major assumptions underpinned Beveridge’s strategy to eradicate these issues from society. The first was children’s welfare, because the “foundations of a healthy life must be laid in childhood”, and that “every living child should receive the best care that can be given to it.” The second was a policy of “comprehensive health and rehabilitation services”, from which the most enduring legacy of the Beveridge Report was born; the National Health Service. The third was the maintenance of employment, which recognised the need for a “national minimum”, a safety net of income support “sufficient for subsistence”, a minimum threshold below which the State would allow no one to fall.

The merits of the report, and what exactly came to be implemented in the post-war period, would be an entire article in itself. What is more to the point of the present essay is how clearly Beveridge, at a time when the outcome of the Second World War was far from determined, saw the link between the scourges of physical want and the other “Great Evils”, and democracy. To quote:

“Freedom from want cannot be forced on a democracy or given to a democracy. It must be won by them. Winning it needs courage and faith and a sense of national unity: courage to face facts and difficulties and overcome them; faith in our future and in the ideals of fair-play and freedom for which century after century our forefathers were prepared to die; a sense of national unity overriding the interests of any class or section.”

This latter sentence is telling, because what the report was envisaging was a concept of social citizenship, a society of reciprocal obligations and contributions independent of the vested interests of a few. The latest plunge of swathes of the population into poverty by Britain’s ruling class comes at a time when our current political spectrum is repugnant to addressing the inequalities of today; the Right is the source of the policies which exacerbate poverty and pillage the environment, while the Left is obsessed with atomising and dividing society along hyper-individualistic lines. The current political spectrum couldn’t be farther from a concept of social citizenship underpinning policy, the basis of which is collectivism and a sense of unity.

Indeed, Tory policy - whether in relation to a pandemic or poverty - is purely one of the narrow self-interest of its class. At a time when democracy itself is in political retreat across numerous countries in the West, the UK included, history reminds us that the relationship between democracy and the welfare of society has always been precarious. And when the lot of much of society reaches a critical mass of despair, reactionary forces, in many guises, have been inevitable. How do we reimagine a new future with a politics so devoid of imagination, evidence, integrity, or ethics?

Beveridge saw that the task of reimagining a future started with a conceptual commitment:

“It can be carried through only by a concentrated determination of the British democracy to free itself once for all of the scandal of physical want for which there is no economic or moral justification.”

There was no economic or moral justification in 1942 just as there are no such justifications in 2022. Yet reimagining a just society requires accepting the premise that the “Great Evils” Beveridge identified are wrong in the first instance. A ruling party that merges the worst of British upper class callousness with a revisionist pseudo-imperialism and venomous neo-Thatcherite economics, is incapable of understanding, let alone accepting, that premise. The Britain of the future is the Bleak House of epochs past.