I was recently referred to a couple of thoughtful essays (‘The Great Forgetting’ by Ruth Gaskovski, and ‘A Pilgrim's Creed’ by Peco), both of which, in different ways, explore how our ability to think, to learn, and to hold memory, are being eroded by our dependence on tech. As we are stripped of our “cognitive liberty” by the insidious screens to which we are perpetually glued, so we become “cognitive migrants”, lost from ourselves and deprived of the attention and intention required to find meaning.

Learning and memory require certain attributes to be present; concentration, repetition, intellectual and emotional engagement, which stand in contrast to the distracted process of rapid information acquisition that having Google at our fingertips provides. In reading both of these essays, I found my thoughts continually coming back to one particular casualty in this war for our minds: books.

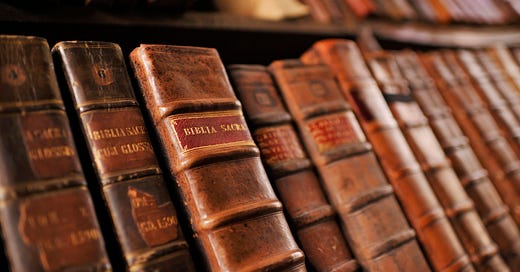

Throughout history, we have assumed guardianship of the words and meanings and messages contained within books, conscious of the sacred role of the manuscript in the preservation of humanity. Books are our bridge from one age to the next; wisdom and learning, turmoils and triumphs, ideas and beliefs, the full catastrophe of the human condition sealed in its time and place and delivered down the winds of history. It is knowledge of the power and richness in such an inheritance that has spurred people to extraordinary lengths, braving danger and death, conspiring and concealing, to preserve books. And it is this same knowledge that, when the thin veil of civilisation slips off humanity once again, makes despots and ideologues burn pyres of books.

Books are defiant. We have never possessed a more potent defence against the human need for control, subjugation, and power. Books are revolutionary, in the very meaning of the word. Literacy was, historically, a skill to be controlled by ruling political and clerical elites, knowing that literacy bestowed intellectual freedom; a dangerous concept for any unfree social order. Books have defied dogmas and tyrants from the Catholic Church to the Soviet Union. The Reformation was as much about literacy as it was about God, for God was only to be found in the reading of the Word; He could not be found without literacy. The ideas and concepts of every leap of humanity, from The Enlightenment to feminism, have been revolutions of books.

A book is an intensely personal object. You are in direct commune with the author, even if they are long dead. Those words on the page are more than type; they are syntactical capture of a moment of original thought in another mind, in another time, in another place. Even if the precise point being conveyed is not original, as often may be for non-fiction, the particular grammatical structure and form of expression, is unique. Each sentence creates a temporal bond between author and reader that transcends distance, compressing years - perhaps centuries - between the moment of conception in thought and writing, and the moment of reception in reading and interpretation.

A book is a living entity; the organic compounds that form the paper, ink, and adhesives that comprise a book breathe vitality into what would otherwise be inert matter. A book will have a life course of its own, from the crisp sheen and slightly synthetic scents of the pages of a new book, the volatile organic compounds break down over time to form the worn, woody wafts of nostalgia that greet us from between the bindings of an old book. They will outlive us, these breathing embodiments of knowledge and thought. The reminiscence waiting on the pages is living memory, and the act of reading a book invokes memory in us by stimulating the senses; touch and feel, sight and smell.

This nostalgia invited by the scents of old books and bookshops has a name: vellichor. Vellichor is a reflective state, inviting the introspection that only secondhand bookshops can gift us; wonder at the mystery of where these books came from, who has read them, and what messages have they carried across the years. This temporal characteristic of books takes on a spatial dimension, their volumes occupying shelves and stacks with their unique times bound between their covers. To bask in vellichor is to experience the Romantic Sublime, a transcendent emotion in awe of this temporal and spatial wonder, beyond empirical measure.

Interiority is the bond that ties us to books. The meaning and essence of a book is found within its covers, which enriches our interior world, transposing us to different places, people, events, and worlds. And as we undergo our “cognitive migration” away from books, we depart from our interior world, and arrive on the hostile shores of the online life, where everything is external. Where no interiority exists; where there is no Self that is separate. Where there is no Self. Where standing in our place is an algorithmic avatar comprised of clicks, likes, and datapoints. And where there are no books; where in their place is words on a screen or in a recording, stripped of all vitality.

Through this bond of interiority, we share a similar fate to books: disembodied by the Machiavellian envelopment of our screens. Removed from the realm of the physical and material into the metaphysical and immaterial. Disembodiment reduces books to an incorporeal avatar, mirroring our own technological disembodiment; hollow online existences stripped of any true essence of being. The despots and tyrants of history saw danger in books and responded by banning and burning. While some trifling analogies can be found today, the Orwellian projections are wide of the mark; the despots of tomorrow won’t have to control books, because no one will possess any, nor read for them to pose any danger.

Wonderful essay! Now I know why I wished before that these 3amThoughts might come as book some day 🙏🏼