It's Not Fascism

The overuse of the term 'fascism' to today's social and political landscape runs the risk of misusing the past the misdiagnose the present.

In 2016, the word "surreal" just beat out "fascism" as the most used word of the year, according to Merriam-Webster. The gratuitous use of the term is not confined to any source; redtop and broadsheet, Left wing and Right wing, the recent trend in brandishing any opposing individual, group, or party as 'fascist', transcends historic political fault lines.

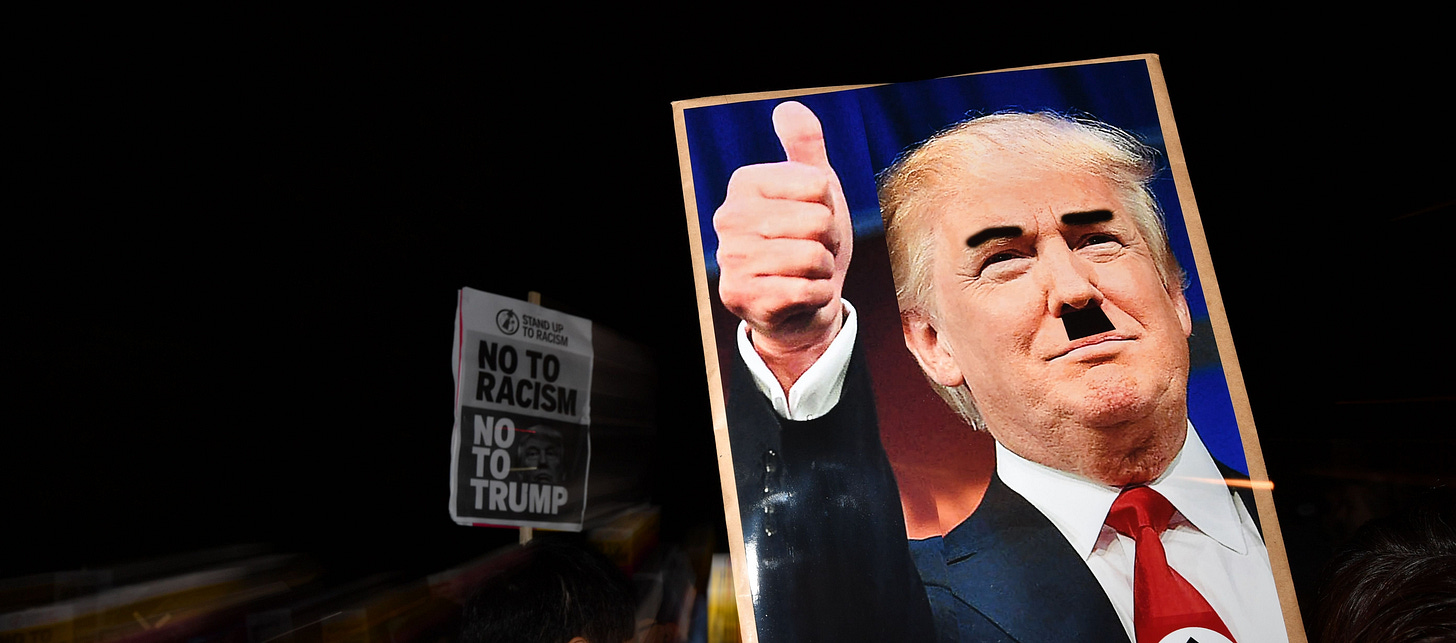

It has become the most common comparison and analogy to current modern leaders, from Viktor Orbán in Hungary to Donald Trump in the US. A 2016 article in The Atlantic even listed out range of terms for Trump: proto-fascist, neo-fascist, fascistic, fascist-esque, fascist-y. The click-bait sensationalism of the word in an attention economy may make it appealing for journalists to deploy, irrespective of the veracity of the context of its application.

It's not just that the context in which it is applied is often intellectually lazy and dishonest. It is also, more often than not, ahistorical. The factors which sowed the seeds for the rise of this political philosophy in the 1920's to 1930's were unique to the circumstance of their time. While there has been an expansion of support for Right-wing parties across Europe and in the US since the 1980's, labelled in the media and published literature under various terms from 'far-Right populism' or 'authoritarianism', comparisons to 1930's fascism should be a cautious exercise, given that in most instances the respective contexts are not analogous. In this regard, the comparisons are, more often than not, over-extrapolated. And this carries the real risk of misdiagnosing the present for what it is, with the unique global and national currents of today combined with an entirely incomparable communications landscape.

Characteristics of Fascism

Griffin & Feldman described three common characteristics of fascism, irrespective of the form of fascism:

Anti-conservatism

A myth of ethnic/national renewal

A conception of a nation in crisis

A defining feature of this political ideology is the exaltation of nation and race above the individual, where the State operated as the source of spiritual renewal and bound nation and race together. This subsuming of the individual into the State was born out of what Griffin termed a 'palingenetic myth', a belief in the total rebirth of the nation, and a constant dynamic renewal that is eternal in its revolution. Thus defined, true fascism is inherently anti-conservative, where conservatism is defined by the maintenance of a traditional status quo, small State, and individual liberties. The conception of a nation in crisis reflects the revolutionary ultra-nationalism that characterises fascism, which emanated from the post-First World War landscape of political struggles in volatile emerging European nation states, defined by a flimsy unification (Italy) or weak, fledgling democracy (Germany and Spain).

Those defining features of fascism go so far as to exclude nominally fascist leaders like Franco and the Spanish Nationalists from being accurately characterised as fascist. Franco merged the Falangists, the authoritarian conservatives often dubbed as fascist, with monarchists and traditional conservatives. In Griffin's scholarship, only Italian Fascism and German National Socialism exhibit all the characteristics of fascism, the binding of racial ultra-nationalism in a mass movement with the State as both paternal and maternal source of spiritual renewal, the roots of an oak tree that would stand resistant to moral degeneracy and threats to the purity of the nation, whose branches would undergo constant revival and grow eternal.

These characteristics may have some capacity for contrast and comparison with today's various Right-wing movements and, to use the media's favourite term, "strongmen", but primarily at a superficial level. However, before considering some of the applications it is important to provide some operational definitions for the modern Right, as often various terms are used interchangeably, reducing diagnostic precision.

Operational Definitions for the Modern Far-Right

The problem with the lazy application of the term 'fascism' to anything that is "not us", is the risk of misdiagnosis of the present. There is a taxonomic and operational definition issue within the academic literature of modern Right-wing movements, and different terms are often used interchangeable, reducing the capacity for precision in understanding trends, antecedents, and potential drivers of these movements, that may differ between countries. Three main terms warrant consideration: 'populism', 'radical', and 'authoritarian', given they may be used to define 'Populist Radical Right', 'Right-wing Populism', or 'Authoritarian Right', but each of these labels are not necessarily analogous and interchangeable.

The term 'populism' is often currently applied as a blanket label for Right-wing political parties, particularly in the media and liberal commentary. This misapplies the concept of 'populism' to authoritarian and nationalist parties, when in reality populism is not confined to any part of the political spectrum, left, right, or centre. Mudde defined populism as a "thin ideology" that plays on a divide between an 'us' and a 'them', in particular the concept of the 'real people' vs. the unaccountable, corrupt 'elites'. De Cleen and Speed have argued that populism goes beyond a mere thin ideology, and encompasses the bringing together of different demands and groups through constructing a vertical distinction between a large powerless group ['the people'] and a small power-wielding group ['the elite'], whose power is illegitimate, irrespective of democratic norms, because it does not derive from the ‘the people’.

Therefore, populism is less of a political ideology associated with a particular location on the political spectrum, and more the mobilisation of this vertical distinction between 'people' and some oppressive force, which depends on the context in which it is applied. For the Right, this tends to be the dichotomising of the 'people' against a perceived unaccountable and unelected technocratic, decision-making elite, a rhetoric deftly deployed by Nigel Farage in the Brexit referendum. For the Left, the large powerless group is marginalised identities and the power-wielding oppressor is the cis-het White male, whose power ('power' in the Foucauldian sense of relations between groups) is considered illegitimate because they do not represent the marginalised identities. For Right-wing populism, all legitimacy is derived, not necessarily from the ballot box or from the authority of, for example, an independent judiciary, but derived from The People; for Left-wing populism, all legitimacy is derived from having a particular identity, or 'intersection' thereof. Thus, 'populism' in isolation has no real meaning, and cannot be fully understood without contextualising how the simplified concept of 'the people' vs. 'the elite' is being mobilised, on what issues, and for what purpose.

The term 'radical' is also an abused label, although while 'populist' tends to be labelled by the Left on the Right, the application of the label 'radical' appears to more commonly go in the opposite direction. Nonetheless, radical in the context of the modern Right is an important operational definition, because it provides the distinction between Left and Right-wing populism, namely the nativist and exclusionary nationalism of the Right. The authoritarianism of the modern Right primarily manifests in themes of 'law and order', and an open rhetoric of 'preserving traditional values'. Radicalism and authoritarianism on the modern Right are often intertwined, as concepts like law and order and the preserving of the nation for 'the people' mesh with stances on immigration and diversity.

These definitions provide more nuanced scope for identifying trends and characteristics within modern Right-wing parties, which may have a blend of populism, nativism and radicalism, and authoritarianism. A better descriptor for far-Right parties may be that these parties are radical and authoritarian, but mobilise populism tactically to meet specific needs, rather than being defined first and foremost as 'populist', which is common in the media.

These movements have their own characteristics, and have emerged in response to recent global, regional, and national forces, that are unique to their time. The liberal media generally draws analogies with the rise of Hitler but still talks about the who/what and not the how, i.e., focuses on superficial character comparisons between individuals ['Trump as Hitler'] or the use of rhetoric. It never focuses on why people where willing to allow those things happen and what they were angry about, and whether within the anger there was any legitimacy which could be addressed to alleviate grievances before they manifest in nefarious outlets. Continuing to make these analytical blunders runs the risk of once again misdiagnosing the entire problem, and allowing issues in society to ferment.

Inaccurate Comparisons to Fascism

Much of the commentary conflates Hitler's Germany and National Socialism as 'fascism', and while they may be synonymous, the origins of the word are Italian and lie with Mussolini and his 1919 formation of the Fasces of Combat forces, which seized power in 1922. Many commentators also draw comparisons between the economic fallout of globalisation, recessions, and austerity today with the economic hardships in Germany prior to the rise of National Socialism, yet ignore that Mussolini's rise to power came long before the Great Depression. The rapidity with which democracies crumbled with the rise of fascism in Europe reflects the myriad turmoils of the time, and economic hardship was central to growing support for National Socialism, but it was not the defining feature. Today, economic hardships may be the central theme underpinning the rise of the radical, authoritarian Right. But there is one major difference: while today's democracies seem incapable of entertaining anything other than the feral market fundamentalism which created the issues in the first place, National Socialism provided a combination of private enterprise and state intervention. There is little comparison between the economic ideologies of fascism and modern free market orthodoxy.

The broad sweeping comparisons between modern nativist nationalism and the ultra-nationalism of 1920's and 1930's fascism also ignores the fact that ultra-nationalism was not just a feature of fascism, but a feature of the political landscape in Europe generally from the late Romantic period through to the Second World War. A defining feature of this political ideology was the exaltation of nation and race above the individual. Perhaps the best example of this from 20th Century European fascism is the concept of Volk in Germany and the deft manner in which National Socialism mobilised this idea of an overarching identity that subsumed the individual into the nation. Volk was nothing new in the 1930's, and the Nazi's certainly did not invent it. It had its origins in the German Romantic writers, and the concept of Volk was to have a central role in the unification of Germany. Volk was not merely a collection of people, but denoted a community bound by ethical and cultural ties. While modern radical Right parties evoke a similar concept of a community bound by cultural ties, the modern Right is also more libertarian than fascist in championing the individual vs. the State, and the idea of a homogenous mass movement is more a feature of the modern liberal Left.

Fascist movements demanded conformity with authority, whereas current Right-wing movements are often highly anti-establishment. Today's so-called 'strongmen', in a ploy which does have resonance from the past, portray themselves as providing an efficiency and decisiveness that their fragmented and divided liberal democratic political orders are unable to. But to overly focus on comparisons with fascist dictators is to miss the manner in which entire political parties mobilise around efforts to alter democratic norms in favour of their own autocratic governance. This trend characterised the Republican Party in the US long before Trump became every waxy Guardian columnists favourite modern Hitler comparator. And it characterises the current Conservative Party policy in the UK, a worrying mix of dismantling government accountability to the citizenry and judiciary, combined with the draconian "this is for your own good" legislation like the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.

While both Mussolini and Hitler were appointed to positions of power, the mechanisms of both instances (appointed, respectively, by a king and a president) are not analogous to modern democracies where, if a country has either monarchy or presidential office (the US aside), they tend to be ceremonial and performative offices of State. This is a crucial distinction, because when political commentators talk of 'democratic backsliding' in modern democracies, it is still in the context of democratic institutions, i.e., Right-wing parties of varying radical and/or authoritarian tendencies are using the very mechanisms of democracy to achieve power and enact policy. There are some broadly similar factors: the undermining of democratic institutions of state, of an independent judiciary, of a publicly-funded independent media, and the reduction of matters of fact to matters of opinion. But the precise contexts in which these are occurring now bear little resemblance to the contexts in which they occurred with the rise of Italian and German fascism. Clear distinctions are required to understand the modus operandi of the authoritarian Right today, beyond attempts to compare them to early 20th Century fascism.

Fascism was also born out of street protest, often in clashes with far-Left actors, like Communist fractions. Today, social movements largely operating through street protest are of the Left and born primarily from identity politics, while the Right operates primarily through electoral channels and focuses on reactionary issues related to globalisation: job displacement, immigration, a sense of a lost national past. While an exclusionary ethnic nationalism that favours the 'real people' is certainly a characteristic of radical Right-wing politics in Europe and the US, many of the issues which the Right is speaking to - globalisation, austerity, welfare, working wages - are legitimate. That they are now coveted by Right-wing parties is a failure of the Left, but as political economists Matthew Goodwin and Roger Eatwell have argued, there is little evidence that supporters of radical Right-wing parties are anti-democratic. Rather, they want more representation, to feel like their grievances have direct channels to potential remedies. A gratuitous label of "fascists" is, at best, intellectually lazy, and at worst, incendiary.

It may also be tempting to draw comparisons between today's 'post-truth' information age, and the propaganda machinery which drove fascist regimes. But if rapid exchange of ideas and information - good, bad, ugly, or plain batshit - is what defines our current technological communications landscape, then the rise of fascism is less an accurate comparison than the rise of the printing press in Europe which catapulted the spread of the Reformation. That period resulted in similar hysteria to that which we see today on various questions, and while modern society has not descended to burning people at the stake over justification by faith alone, our communications systems did allow for the global rapid spread of Covid-19 and the propagation of myths that the virus was a hoax, vaccines a conspiracy, and related utter falsehoods that have cost people their lives. The critical difference is that while the mobilisation of propaganda, most effectively by National Socialism, served to reinforce the subsuming of the individual into the State, today's communications landscape drives increasing fragmentation of individuals into a multitude of belief-silos.

The Cost of Misdiagnosis

The problem with specious comparisons to fascism and fascist dictators is that they are often deployed as pejorative characterisation of a current personality, not any rigorous contrasting with the events of history to the events of today. There is in fact a well known fallacy for this: Reductio ad Hitlerum, where references to Hitler and the Nazis are deployed to discredit an argument. The ubiquitous use of the term 'fascism' to describe anything from a point of view someone doesn't agree with to current political movements and figures represents the twin of that fallacy: Reductio ad Fascism. It is only deployed as a conversation-ender. It can never be a departure point for meaningful dialogue. As Orwell stated in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the term 'fascism' had already been relegated in meaning to simply "something not desirable". The lazy application of the term suits the zeitgeist, in which any side of the political spectrum is only capable of representing the other in the most disparaging of terms.

Yet in all of this, it remains difficult to argue that democracy itself will disappear entirely in countries with established post-war democracy. This is another problem with the comparisons to 20th Century fascism, because the counterfactual assumption is that we currently live in fully functioning democracies at risk of backsliding. Yet is arguable that many democracies are not fully functioning in the true sense of government of the people, and for the people, at they are certainly not by the people. On the contrary, some recent insightful analyses point to a veneer of democracy, in which we have certain characteristics like candidates and open elections, but in reality exist in a "neo-feudal" model where an increasingly powerful and detached economic and technocratic elite dictate on moral issues, like climate change, and direct the trajectory of society, often independent of politics. These movements are not a movement of the masses, but a movement of a very narrow segment of society - "the clerisy" - educated, technologically advanced and savvy, wrapped up in a cloak of environmental and social justice piety. This is the new clerisy, not a mass movement where the individual is subsumed into the bosom of the State.

What emerges may look like democracy on paper, but the majority will be all but excluded from any meaningful control over their lives, which will likely fuel more reactionary, populist, and radical Right-wing pushback with increasing support for authoritarianism. While the core characteristics of early 20th Century fascism are largely incomparable to today, the one warning that we should take from history - independent of fascism - is that democracy can be eroded and collapse from within.

Whatever may emerge, the overuse of the term 'fascism' for today's social and political landscape runs the risk of misusing the past the misdiagnose the present.

Gives me a lot to think about, thank you! Always intriguing how poignantly you express such important points - imho, we must not afford "reducing diagnostic precision", there's too much at stake.