Opinion Absolutism and Impoverished Perspectives

The moral imperative of our culture is to incubate yourself within only the ideas you already believe.

I hadn’t intended to interrupt the Israel-Palestine series, but this particular thought is something that has been ticking over the back of my mind for awhile and I had some time on a flight to kill, so here it is on a page. And as a brief essay, it may provide a little respite from the monographs of the Israel-Palestine series. In fact, the central point of the present essay is also relevant for that particular series and the nature of the dialogue we’re subjected to on the topic in the media, social media, and on the streets.

I want to propose a hypothetical to you. Imagine you’re at a lecture or conference where a particular speaker is going to be delivering a keynote talk. And this hypothetical speaker, we’ll call them Speaker X is here to present on Issue Y. Issue Y is a topical and politically divisive issue, and the conversation has, as is predictable for our era, descended very quickly into Position A and Position B. Online there is no quarter given; “only a literal fascist would support Position B” cries Team A, who support Position A unequivocally and without thought or question. Team A faces off in the comments section against Team B, who retort; “you’re either Position B or you're a literal Nazi”, and support Position B unequivocally and without thought or question. Members of both Team A and Team B solely listen to, read, and reshare “content” from voices aligned unequivocally and unconditionally with Position A or Position B, respectively.

Speaker X has been a vocal supporter of Position A. Now you, Dear Reader, are one of the silently confused ones; you’re not really sure where you line up, but on balance you currently lean towards Position B. However, you’re also uncomfortable with the fact that Team B members have pressurised the organisers to revoke Speaker X’s invitation, citing “literal violence” as a very allegorical reason, tried to block Speaker X’s entrance to the conference, and some have even glued their hands to the floor in protest, which strikes you as both unnecessary and mentally unstable. At the very least, you’d like to hear what Speaker X’s reasons are for supporting Position A, and see whether you feel persuaded by any of them. Speaker X begins their presentation, and a member of Team B breaks down sobbing and demands to be taken to a “safe space” to be shielded from the harm of words and ideas, which strikes you as bizarre because you saw this person at a protest the day before screaming “Intifada revolution!”

Speaker X eventually gets going and you pay attention. You find their tone and delivery smug, condescending, and dismissive, and start to form a negative impression of their character. In fact, you find yourself really disliking them. Speaker X has three specific points to their lecture in favour of Position A. On two of those points, you’re convinced Speaker X’s case is pretty weak, relying on rhetoric and hyperbole. In fact, in thinking through Speaker X’s arguments on these points, you gain some new thoughts as to why you align more with Position B on these points. In fact, on one of these points, you find Speaker X’s rhetoric to be inflammatory and provocative. However, on their third point, you find Speaker X to be quite persuasive. Their point is logical, measured, and supported by some evidence you hadn’t previously known or considered. You’re squirming by your positive reaction. The forces of cognitive dissonance are storming your prefrontal barricades; you’ve formed a dislike to Speaker X personally, and they’ve said a couple of things that may, in the popular parlance, be deemed “problematic”. How do you reconcile agreeing with this final point in favour of Position A?

This hypothetical dilemma is why the principle of freedom of expression and speech is crucial to any healthy, functioning society. Let’s place you back in front of our hypothetical Speaker X. Recall that you dislike their tone. So what? Responding to tone is always a lower form of argument; substance is what matters, not style. Recall that you form an overall negative opinion of Speaker X’s character and disagree with 90% of what they have argued for, but they’ve landed one very valuable perspective. This is one of the critical benefits to freedom of speech, because there is no other way you probably would have exposed yourself to Speaker X’s views, and yet you’ve gained something valuable from doing so in two important ways; the two points you disagree on have helped buttress your own perspective on Position B, while you’re now able to acknowledge that Position A does have some valid arguments in favour of it. Your subjective sensibilities of Speaker X are irrelevant, if you can hold that in tension, because it is the accuracy of their ideas that matters. Yet in recent years the evaluative criteria has shifted to one which gives validity to ideas and opinions based on the most superficial, external representations of identity. But identity does not validate ideas; ideas standing up to being weighed and measured in open scrutiny does.

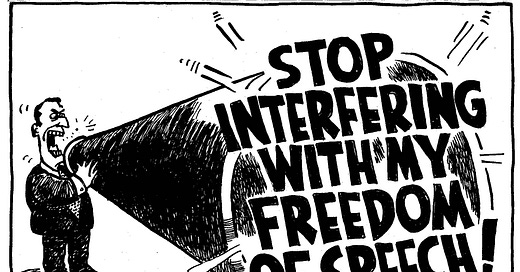

Although the debate around freedom of speech is often reduced to politicised tropes, it is important to separate the debate from the principle. The principle is a fundamental pillar upon which an open society is built, because it acts as a stress-test and filter for the marketplace of ideas. It articulates a very basic premise that everyone is entitled to express their idea or opinion, but not all ideas and opinions are equally valid. In the freedom to express that opinion is the implicit acceptance that the opinion will be held up to scrutiny, evaluated for its accuracy and value. Freedom of speech is the public wing of the scientific method, of academic freedom to articulate, pursue, and test theories and ideas. Both of these act in service of a defining characteristic of democratic, open societies: the capacity for error correction. And when these freedoms are denigrated, that capacity for course correction is eroded. At its core, freedom of expression holds that pluralities of perspectives, ideas, and opinions, in an environment that puts those ideas to the test of open scrutiny, allows the most durable and useful to emerge.

One of the defining characteristics of our polarised, fractured public square is that we have incubated a culture of absolutism in discourse. We demand that the people around us “take a stand”, “pick a side”, display the colours of Team A or Team B. Within this incubated absolutism, people are stripped of their capacity for inquiry, for curiosity; for the humility of “I’m really not sure” or “I haven’t made up my mind yet.” Stripping people of their room for inquiry and curiosity robs them of their intellectual agency. This is intentional; while the demand to “take a stand” is often couched in moralistic “right-side-of-history” rhetoric, it is nothing more than a demand for ideological conformity. Within this absolutism, humility and curiosity are bludgeoned by arrogance and righteousness, usurped by the ignorance of certitude.

The consequence of absolutism is monomania, an obsessive entrenchment on specific issues which acts to constrict our vision of a broader scope of perspective, and the wider picture. And this absolutist, reductionist culture then shapes the public square into diametrically opposed fealties. The voices that are then elevated are those that demonstrate unquestioning commitment to the cause, along with shock jocks and controversy cruisers. Nuance is denigrated, context is abhorred, outrage and contempt are celebrated as virtues. Each side, Position A and Position B, are filtered through the reducing valve and emerge as opposed ideological monocultures. In an absolutist monoculture, style and subjective moral sensitivities are celebrated over factual accuracy and theoretically soundness. Little wonder we’ve arrived at this point of impoverished perspectives and narrowed opinions.

In our hypothetical example of Speaker X, in our absolutist culture I can guarantee you that nine out of ten people around you would reject that one valuable perspective because they’ve decided Speaker X is a “literal” something or other. Their own perspective is further impoverished as a result; their intellectual faculties are withered to hearing only those voices they perceive as in 100% lock-step alignment with their own positions. When people won’t consider that someone they dislike or disagree with has anything of value whatsoever to contribute, that says more about that person than it does the figure they dislike. It says that they don’t have a sufficiently calibrated intellectual fabric to know that they can take that one single perspective from Speaker X, and nothing else, without seeing it as a moral failing. It screams of frailty in their own understanding of a given topic or issue. They are afraid of even opening to a perspective or listening to someone they perceive as in favour of Position A, because if they did happen to hear something they are inclined to agree with, they cannot reconcile it against feeling they have trespassed against Team B, against their ideological monoculture. Best to stay safe with the sloganeering and manufactured outrage.

We’ve been incubated into a culture where intellectual rigidity is considered a virtue, the virtual high-fives that come with displays of righteous indignation at anyone perceived as transgressing against the tenets of the faith. We are reduced to such rigidity because the criteria for evaluating an argument or issue has shifted entirely away from facts and evidence and weighing the balance of substance, to wholly subjectivist and relativist criteria which centre the speaker themselves as the criteria for evaluation. This is, as Jonathan Rauch has long argued, the antithesis of the Western canon of reason; a fact is only deemed so if it is true independent of the speaker.

The supplanting of that canon with postmodern relativism has created a culture where “positionality”is key, where the truth of a fact is relative to the perceived moral purity of the speaker, and where moral purity is itself defined by the virtues attributed to specific “oppressed” identities. Thus, a person’s ideas and perspectives are either uniformly affirmed or dismissed not based on the veracity of their arguments or factual robustness, but on who they are and where their politics line up. On whether they say everything someone already believe to be true anyway. There is no sense making to be found here, just whataboutisms, tautologies, and incoherence.

I would hope, with all sincerity, that you do not agree with everything you read in 3am Thoughts essays. I would also hope, at least, that on whatever you may disagree with, you would also feel that you could offer your perspective confident it would be considered, respectfully and honestly, as a stress-test of my position at the time. If it didn’t survive that test, it would be cause for me to alter that position and consider a different perspective. And I would hope, in return, that whatever you find yourself inclined to disagree on would also serve as a stress-test to your own position and, if you felt it warranted, could perhaps shift your own perspective.

And this is the whole game, this is how this whole dance works, this thing we sometimes call freedom of expression or “the West” but at its core is simply a particular epistemology of how to build a society that tolerates differences and doesn’t fall to the default human temptation to simply deal with difference by eradicating its presence.

Yessssss.

Powerful, and beautifully written .. and leaving me ‚humble‘.. I hope it is also ok to just thank you for this (much needed) reminder 🙏🏼