8th May - Victory in Europe (VE) Day - every year, is one of a handful of dates scattered throughout the calendar that give me cause to pause, and reflect. 6th June is another, the date of the Normandy landings, and Remembrance Day on 11th November. The focus of pausing on each day is, of course, remembrance itself; the colossal sacrifice of an entire generation to bring about the end of what was, in both Europe and Asia, a struggle for civilisation itself against the monstrosities of the Third Reich and Imperial Japan.

In the West, the typical narrative scope of VE Day is narrow; Western Allies, emphasising America, Britain and France, helped bring down Hitler's Germany, with a hat-tip to the Russians for taking Berlin. In reality, while America certainly deserves the lions share of credit for bringing down Imperial Japan, Soviet Russia primarily paid the butcher's bill to end the war in Europe. Yet today, it is Russia dealing death in the first land war on European soil since the cessation of hostilities 77 years ago.

77 years on, we are also sufficiently removed for the events in question to benefit from a revived, vibrant historical scholarship providing badly needed perspective on both the Second World War in Europe and the shaping of the post-war geopolitical landscape. And this VE Day, with war raging in Ukraine, is an apt time to consider some perspective.

If you have a passing interest in this period, there are two narratives you've likely internalised without much realising, a combination of dazed school history classes and the odd Second World War or Cold War movie. The first is what historian Norman Davies has long sought to dismantle, known as the “Allied Scheme of History”. The second narrative is the phoenix-from-the-flames story of Germany's rise from the post-war rubble to take its place at the centre of the great post-war European peace project, the European Union. Both narratives are so strong that they have influenced post-war geopolitics in Europe, particularly with regard to Russia.

In the context of the Second World War period, the Allied Scheme of History views Germany as the root of militarist aggression in Europe, that National Socialism can be ascribed all evils related to totalitarianism, anti-Semitism, and mass murder, and takes a benign view of Stalin's Russia as a benevolent ally that, alas, developed some friction from 1945 onwards. This likely influences you in ways you don't realise. You likely know off the top of your head the numbers of human beings murdered in concentration camps, but you've no idea how many were murdered in gulags; you likely (and rightly) view Hitler as the epitome of evil dictatorships, but you don't quite place Stalin in that category (you might have a general heuristic of 'Communism = bad'); and you likely see the Second World War in Europe as good vs. evil with the Allies vs. Germany, rather than as a cataclysmic fight to the death between two diametrically opposed totalitarian ideologies in Nazi Germany vs. Soviet Russia.

The first narrative is problematic because it attempts to gloss over historical reality: that distinguishing between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia is hairsplitting, and the only meaningful distinction was between the respective ideologies of both regimes. The Second World War started with the expansion of one evil totalitarian dictatorship and ended with another. This was acknowledged at the time: the U.S. and Britain knew who they were getting into bed with in the form of Stalin's Russia. And they knew this was required to bring down Hitler's Germany. It was also acknowledged that Soviet Russia were paying a blood sacrifice to achieve this end; the U.S. never made Russia pay a cent of the lend-lease equipment provision to Russia back, but bankrupted post-war Britain by ensuring Britain paid the full debt (which was finally paid off in 2015).

Toward the final months of the war, several Allied leaders, who saw Soviet Russia for what it was, wanted to start rolling back Russian gains in Eastern Europe, knowing what was to come. The loudest voice in this regard was U.S. General George S. Patton, who wanted to take what was left of Germany's military and put them in U.S. uniforms to turn around and fight the Russians back. (Aside: if you like Second World War conspiracy theories, one is that the car accident in which Patton was killed in 1945 was no accident at all, but a deliberate act to silence him because of his vocal views on Russia...). The Allied Scheme of History has swept under the rug the fact that many within the American and British hierarchies saw clearly that the Second World War endgame was the replacing of one totalitarian regime with another dominating the map of Europe. But the official narrative was that Russia were our benevolent allies in the great crusade against the sole evil in Europe, Nazi Germany.

And this is where the second narrative becomes relevant, because Germany's post Second World War place in Europe has been defined by it, both internally and externally: the national reckoning with the deeds of the Third Reich. This post-war reckoning may be divided into two distinct phases. The first is what historian Florian Huber termed “the pull of silence” in the immediate post-war period, from 1945 through the 1950's, a period of denial and evasion by the generation who had participated, or at least lived through, National Socialism. The second is the period of hard reckoning which began with the post-war generation who came of age in the early 1960's, demanding accountability and ownership for the horrors inflicted by their parents generation. This has defined not only Germany's view of itself since, but defined its foreign policy, most notably with Willy Brandt's concept of “Ostpolitik”, leaning eastward - particularly toward Russia - with the intent of benevolent cooperation and mutual benefit.

The first period is encapsulated by a paragraph from Huber's stomach-turning book, ‘Promise Me You'll Shoot Yourself’ about the fate of ordinary Germans in 1945 and the immediate attitudes following the war. In reference to Hannah Arendt's experiences after returning to Germany in 1949, Huber writes:

“Everywhere she looked, she saw Germans running away from reality. When she spoke to them, they totted up their suffering and compared it with that of others. When she criticised them for this, they icily deflected her remarks. When she asked about the reasons for the catastrophe, they dodged the question with vague talk of the wickedness of mankind. Arendt caught them shuffling out of responsibility with a variety of tricks: self-pity, distraction, apathy. Their refusal to confront what had happened came at the cost of genuine feeling.”

The second period, the great reckoning with the past, began in the 1960's and developed in earnest over subsequent decades. Per Huber:

“One by one, the painful taboos were overcome...The postwar code of silence gave way to an obsessive interest in the Nazi's crimes as the country came to terms with its history. Facing up to atrocities became part of German identity.”

But as Huber and other historians - Davies, James Hawes, and Neil MacGregor - have observed, this dedication to owning the past, while laudable, has also come at a cost, both nationally and for foreign policy. At the national level, the drive to view Germans only as culprits has written out from history enormous tragedy that befell ordinary Germans during the war. The sense that any sort of acknowledgment of these facts is tantamount to slipping back to the denialism of the 1950's overpowers the ability to have a more balanced assessment of the historical record. At the foreign policy level, while there is no doubt that Germany has engaged with Russia in good faith, this good faith - particularly that of Angela Merkel - has been manipulated by Putin for Russian leverage. As a result, Germany is primarily keeping the lights on the in the Kremlin and the fuel in Russian tanks in Ukraine with its gas and oil imports.

Both of these costs of the postwar reckoning stem from what James Hawes recently pinpointed about Germany, that the “nation...is, at bottom, scared of itself.”

That if Germans:

“do not insist on being the hardest-saving, most carefully consuming, most ecologically responsible, most pacifistically inclined, least nationally patriotic people in Europe, they will suddenly flip into Nazis.”

But German tanks are not rolling in Europe; German soldiers are not raping and murdering in Europe; Germany is not an autocracy invading sovereign countries in Europe. 77 years on, all of this is Russia.

And few of any generation in Germany today are beyond the post-war generations. It is time for Germany's post-war reckoning to move into another phase. There is not a single nation on earth who has undertaken this national process of reckoning with the past, of owning the sins of the fathers, with the vigour of Germany from the 1960's onwards. Japan has buried its head in the sand about its horrific campaign of murder across Asia from 1931 onwards. The U.S. still cannot muster any productive dialogue about the legacy of slavery without it descending into politicised slur campaigns. Britain still has a stiff upper lip about its colonial past. And Russia is a resurgent, revisionist, aggressive power, picking up where the Tsars and Stalin left off.

It is as if we need an army of Robin Williams' in wooly sweaters to knock on the door of every person in Germany born after 1945 and walk in saying “it's not your fault” repeatedly until the moment of catharsis. In this third phase, it should be possible to hold both the accountability for the past and the acknowledgment that, yes, ordinary Germans' also suffered, in tension, one not diminishing or denying the other. And Russia's murderous war of aggression and conquest in Ukraine should serve as the catalyst for this, because it is in the East that is the source of much of this historical suffering.

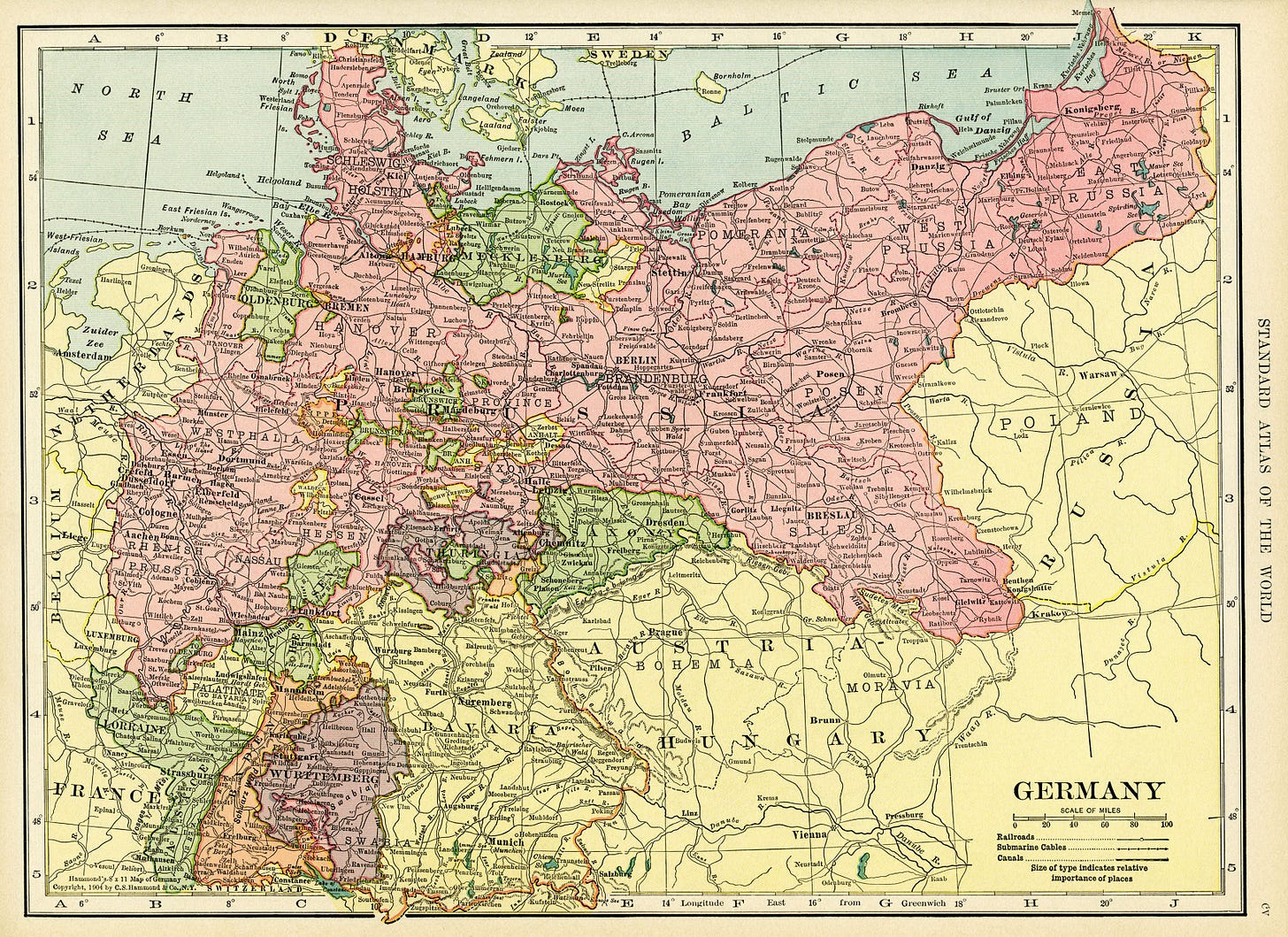

We should be able to acknowledge, as Davies has, that the Potsdam Conference that resulted in the taking of a fifth of German sovereign territory (see the extend of the eastward projection of the map in red, below) had no legal standing; that neither did the Allied Control Authority (which ran occupied postwar Germany) Law No.46 of 1947 which extinguished the State of Prussia (which despite the connotations that name holds now, the state itself consistently voted left-wing throughout the interwar period, including in the final election before the Nazis took power).

Or that of the 190,000 German civilians trapped in Königsberg when the Russians seized the city, only 50,000 were returned to Germany in 1949. Or, as MacGregor illustrates in ‘Germany: Memoirs of a Nation’, that the expulsion of 14-million Germans from the fifth of Germany's historical territory in the East seized by the Allies and Russia constitutes one of the largest single forced migrations in history (only rivalled by the aftermath of the partition of India and Pakistan). Or that an estimated 2-million German women were raped by Red Army soldiers in the apocalyptic final months of the war. Or that some of the largest mass suicides in history took place in towns throughout East Germany during those months, mothers tying themselves to their children with ropes and plunging into icy rivers rather than fall into the hands of the advancing Russian army (with most men dead or at the front, the suicides were largely women, children, and the elderly).

This all happened. And none of it excuses, explains, or diminishes the monstrosity of the crimes also committed in the name of the Third Reich. It matters that we are able to hold both in tension because for this post-war Germany, the debt is paid: we cannot change the past, but we can ask to own our histories and learn from it. Germany has made this ownership of the past a part of its national psyche. It is a model democracy, and a lynchpin of the imperfect European project.

This VE Day, in addition to paying homage to the Allies who brought about the end of the Third Reich, I'm also acknowledging that Germany will never again be the country it was between 1933 and 1945. But as I write this, I cannot say anything of a similar vein about Russia, because the Russia we see in Ukraine today eerily resembles a Russia we’ve seen before in history. And within her borders are victims as well as culprits.