What Comes Next for Iran?

The coming presidential election will cement theocratic control and perpetuate the Islamic Republic's empire-by-proxy.

One would generally expect a sense of discomfort that arises at the thought of celebrating the death of any fellow human. Yet we humans are a species prone to the production of monsters, and vulnerable to said monsters attaining power. There are thus exceptions to the general rule of discomfort at the celebration of death when the death in question occurs to an Archetype of all that is evil in humanity. And so it is with the death last month of Ebrahim Raisi, the president of the Islamic Republic of Iran; I offered no condolences, I don’t care if he was some mother’s son, I don’t care who wept for him. To do so would seem such a hollow, false pretence of humanity for someone whose inhumanity has been their political signature.

Raisi made his name as an Islamist prosecutor and jurist within the theocratic judiciary of the Islamic Republic, rising from regional prosecutor in 1980, at just 20 years of age, to Prosector of Tehran from 1989–1994, and ultimately to the head of the Iranian judiciary in 2019 where he served until his “election” as president of the Republic in 2021. As Prosector of Tehran, where he earned the nickname “the Butcher of Tehran”, Raisi headed up a “death commission” where he oversaw the arrest, detention, execution or disappearance of thousands of political dissidents. He did not leave this reputation behind him as a prosecutor; in response to a wave of protests against a substantial increase in the price of petrol in 2019, he oversaw the violent repression of the demonstrations with the usual methods; lethal use of state force, arbitrary arrest, detention, disappearances, and torture. In this respect, Raisi represented the very worst of the Islamic Republic, doing what it does best.

While Iranians let off fireworks and celebrated at the news of Raisi’s demise, one couldn’t help but feel some discomfort at the prospect of what the sudden presidential vacancy may bring. Discontent with the regime is nothing new; protest against the regime is nothing new. Waves of civil unrest have flashed in recent years; 1999 student protests at Tehran University; the 2009 Green Movement protests against the rigged “reelection” of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; 2017, 2019, 2020, and 2021 in response to economic conditions; additional 2020 protests against the shooting down of the Ukrainian Airlines flight 752 by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC); 2022 in response to Mahsa Amini’s murder. Civil unrest and protest in Iran follow a similar pattern; those outside Iran and in the West express hope and the usual platitudes of “solidarity” are uttered. The regime, however, doesn’t much bat an eyelid and simply unleashes the full apparatus of repression on hopelessly unmatched protestors. The cold, hard reality is that the Islamic Republic as a regime is “too rigid to bend and too ruthless to break.”

To understand why this is the reality, it is important to highlight the particular structure of the regime, known as “the parallel state”, a term reflecting the positioning of the state institutions between the elected government headed by the president, and the Islamist clerical theocracy headed by the “supreme leader”, i.e., an Islamist cleric, known in the West as “the Ayatollah”. In this structure, the institutions of Islamist theocracy sit “parallel” to the government, responsible for the implementation of Islamic law over society. This structure means that any hope for reform, particularly less stringent enforcement of Islamism over society, is vested entirely in the government and the office of the president. And over the past three decades, the presidency has been the aspiration for reformers and modernising political movements within Iran.

Mohammad Khatami served as president between 1997–2005, during which he sought to implement a more secular, modernising agenda for domestic social issues and to temper aggressive Islamic sectarianism and anti-Americanism in foreign policy. Mir-Hossein Mousavi ran for president in 2009 against Ahmadinejad on a similar reformist platform as Khatami (Khatami withdrew from the presidential race and endorsed Mousavi to consolidate votes in one reformist candidate); the announcement of Ahmadinejad as the winner of the election sparked the 2009 protests. Hassan Rouhani, who defeated Ahmadinejad in the 2013 election and served until 2021, was also a reformist and moderate president who sought to cool the temperature of Iran’s foreign policy and improve relations with the West.

It is in this context of reformist and moderate candidates vying for and being elected to the presidency that the election of Raisi as president in 2021 must be understood. Presidential candidates in Iran must be approved by a 12-member clerical body, known as the Guardian Council. While in the past three decades, they had allowed a slighter wider scope to reformist candidates, the Guardian Council adopted a more hardline interventionist approach for the 2021 election. The reformist presidents threatened the primacy of theocratic rule. Khatami’s presidency mobilised the conservative hardliners and clerics into action, fearing an erosion of theocratic control over Iranian society and foreign policy. With Ahmadinejad’s “reelection” in 2009, it was the Supreme Leader and the parallel state that stepped in to endorse and consolidate Ahmadinejad’s “victory”. Rouhani’s efforts at reaching a historic agreement with the U.S. on Iran’s nuclear programme, in attempts to lessen the burden of economic sanctions and improve domestic economic conditions, provided the pretext for the clerics and conservative hardliners to push to impeach him (although this didn’t come to pass). By 2020, the Guardian Council was intervening to disqualify reformist and centrist candidates from standing for parliamentary elections, resulting in a default overwhelming dominance of conservatives in government.

Raisi’s election as president in 2021 thus represented a symbolic end to three decades of reformist ambitions, concentrating theocratic power and cementing the hegemony of the parallel state. The Guardian Council disqualified any reformist candidates from standing, paving the way for Raisi’s “election”. Under Raisi, the president and government on the one hand, and the parallel state under the Supreme Leader and clerics on the other, were cemented in alignment. The concentration of domestic power within the parallel state had also been provided with an external stimulus in the form of the Trump administration’s naive foreign policy towards Iran, which rather than exploit domestic political divisions in the country, adopted a blanket strangulation approach to economic sanctions and withdrew from the 2015 nuclear agreement. The result of this approach was increased control of Iran’s financial sector by the IRGC and an emboldened and hostile Iranian foreign policy in the Middle East. Thus, Raisi’s election not only formed the coup de grâce to the reformist movement in Iranian domestic politics, it represented a shift in the Islamic Republic’s regional role from an incoherent sponsor of disparate Islamist militias to a coherent foreign policy as overt orchestrator of regional chaos.

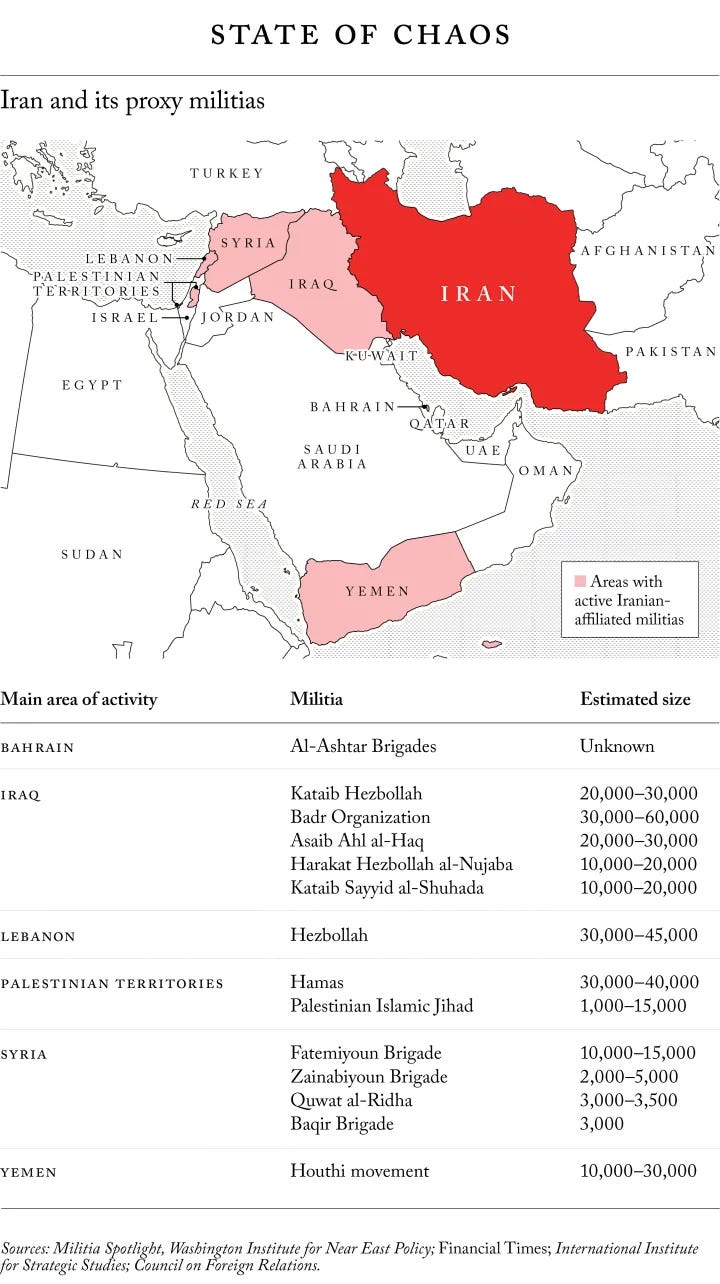

If events like the attack on the Saudi oil refinery in 2019 and attacks on American military bases in Iraq in 2020 may have seemed reactionary isolated incidents, events post-October 7th should make the coherence in Iranian foreign policy clear. Judged on their own, the actions of Hamas from Gaza, Hezbollah from Lebanon, and the Houthis from Yemen, may seem independent; judged as part of the fabric of the Islamic Republic’s “axis of resistance” and a different picture emerges, one of a coherent foreign policy designed to leverage asymmetric warfare to Iran’s advantage against its primary adversaries: Israel and the U.S. As the figure below illustrates, the empire-by-proxy extends over Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and into Yemen. Suzanne Maloney of the Brookings Institute has reported that between October 2023 and February 2024, attacks by Iran’s proxy militias have resulted in 186 U.S. military casualties in the Middle East. The scaling up of attacks by the Islamic Republic’s proxies throughout the region over the past seven months may appear opportunistic, but in fact represents a careful cultivation of empire-by-proxy that seeks to shift the balance of power in the Middle East towards Iran's brand of militarised pan-Islamism.

It is within this context that the coming election must be understood. Raisi’s death is not a setback for the regime, but another opportunity to cement the ideological alignment of government and theocracy, under which Iran’s regional foreign policy manoeuvring can continue in lockstep. Among the runners for the forthcoming election are the ultra-conservative Saeed Jalili and hardliner Mohammed Baghar Ghalibaf, a former IRGC commander and current speaker of the Iranian parliament. Of six candidates, only one reformist - Masoud Pezeshkian - has been approved to stand by the Guardian Council, and this appears to be largely for show; Pezeshkian does not appear to have a sufficient public profile to concentrate reformist votes in his candidacy, and his voice is overwhelmed by the conservative candidates. Indeed, while thousands of Iranians, particularly in the diaspora, celebrated Raisi’s death, bear in mind thousands also gathered at the Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine, a religious site in Tehran, chanting “death to America, death to Israel”, and waving the flags of Iran, Palestine, Hamas, and Hezbollah. Both the Zeitgeist among religious conservatives and the leveraging of the Guardian Council almost guarantee that in the context of low voter turnout, as disillusioned reformist voters abstain, a hardline conservative will be elected as the next president of Iran.

This election occurs at a time when, just in the past week, it has been reported that Hezbollah is now mobilising with more purpose to attack Israel from the north, while Iran has reportedly agreed to facilitate the transfer of Taliban fighters to support Hezbollah. To what extent such escalation will manifest remains to be seen. Yet the Islamic Republic does not necessarily require such escalation to exert its influence as the regional hegemon. This is the luxury of asymmetric warfare, whether in hard material conflict or rhetorical posturing; simply keeping the region mired in apprehensive instability is sufficient for the purposes of Iran’s foreign policy. Suzanne Maloney summed up this asymmetry:

“Iran now has the default advantage over the United States because it does not actually have to achieve anything material in the near term. Chaos itself will constitute a victory.”

If there is a signal in the Middle Eastern noise for a regional realignment to thwart the chaotic designs of the Islamic Republic, it lies in the response to Iran’s attack on Israel in April this year. The response laid bare the ignorance of framing the Middle East as “Israel/America/the West vs. Arabs/Iran”; Jordan mounted air defence with Israel, while the Gulf states, including the Saudis, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates, collaborated with intelligence sharing, continuing relationships with Israel on security issues that views Iran, not Israel, as the primary threat to regional stability. One school of thought is that the October 7th attack was motivated by the increasing normalisation of relations between Israel and Arab states, the Gulf states in particular, in which “the Palestinian question” was not a concern for any party, pan-Arab “solidarity” revealed for the charade it has always been. Thus, a policy priority for Middle Eastern nations to isolate an increasingly belligerent Islamic Republic would be to ensure that the process of normalising relations between Israel and, particularly, Saudi Arabia, comes to full fruition.

Nevertheless, the grand sweeping narrative scope of inter-state policy discourse always has the effect of losing focus of the people on the ground for whom these overarching conflicts and issues directly impact their daily lives. For the people of Iran, the calamity will continue to play out, and there is little doubt that what comes next is an extension of the status quo. The regime is too rigid to break from external pressure, and too ruthless to break from internal pressure. Its empire of rubble across Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Gaza, is a macabre catastrophe of human suffering. The raison d’etre of the Islamic Republic is continued, perpetual Islamist revolution, “axis of resistance”, “death to America”, and “death to Israel”. The regime has no conception of nationhood beyond its own crippling theocratic doctrines. One shudders to think of what level of suffering the Iranian people will have to endure to free themselves from the regime. Until then, chaos will indeed constitute victory for the Islamic Republic, pyrrhic as it may be.