Asymmetry and the Dilemma of Self-Determination

Part 2 of attempting to make sense of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

A potent mix of forces brought us to this point: the strategic location of the Levant and its historical coveting by peoples and empires from antiquity; the Israelite tribes dating to the Iron Age; the Arabisation of the region between the 7th-9th Centuries; the modern historical interplay of two fallen imperial powers, the Ottoman Turk’s and the British; the antecedent presence of Jews and Arabs in the Ottoman region we now refer to as Palestine; the origins of the contemporary Zionist movement stretching back into the 19th Century; the proliferation of European anti-Semitism, ongoing pogroms against Jews culminating in the Holocaust; the original United Nations (U.N.) partition plan in the final years of the British Mandate; the multiple attempts to annihilate the fledging State of Israel by surrounding Arab nation states; and the creation of occupied territories under Israeli military control over lands intended for a Palestinian state.

If you haven’t read Part 1, you’ll be best served reading Part 1 and then come back to this second part, which builds on the first. For example, if you see a reference to “the 1967 borders” or “the British Mandate”, it is assumed you’ve read Part 1. This is for the sake of the narrative flow of this second part,and will allow us to get a bit more granular on some specific aspects of the saga that provide crucial context, such as the operation of the League of Nations during the Mandate period. This second part aim sto expand on the concepts of minority rights and self-determination as understood in the Mandate period, its relevance for the origins of the state of Israel, and explore the various asymmetries that exist as realities on the ground, and how both the historic and extant realities intertwine in these asymmetries.

Given how unhinged and ugly the online conversation and the real-life reactions to recent events have become, there will also be a Part 3. The repugnant responses show that people in the West, wholly unconnected to the conflict, comfortable and safe with their luxury radical-chic beliefs, are deliberately dispensing with empathy and understanding in favour of descending into feral tribalism dressed up as “activism”. But that can wait.

Yuval Harari recently discussed the problem of two traumatised peoples who, when further traumatic events occur, become so consumed with their own grief that they are unable to hold any space for empathy or understanding for one another. This has reinforced my aim of attempting to write this series as dispassionately as possible, with intellectual honesty and epistemic humility, acknowledging that not even a full academic book on the subject could likely cover all angles to any satisfaction. The fault of any omissions are my own.

The Dilemma of Self-Determination

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, multitudes of the varied peoples of Europe and the Middle East found themselves within the imperial boundaries and rule of two Empires, the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The end of the First World War heralded not only the beginning of the end for the European and Ottoman Empires, it brought with it one of the defining characteristics of the interwar years: an ambitious international attempt to create a rules-based order for supporting the realisation of national self-determination. This concept was not new, but traced its origins back to the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which brought an end to the Thirty Years' War. The Peace of Westphalia was the first formal treaty to recognise religious tolerance as a political principle, and to formalise a process of inter-state relations in which conflicts could be settled by diplomacy and compromise.

Often dubbed the “Wilsonian order”, reflecting the impetus of then U.S. President Woodrow Wilson for the foundation of this international order, the vehicle to facilitate the process of national self-determination was the League of Nations, born out of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. With the simultaneous collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires and the Kingdom of Prussia, long-suppressed cries for national self-determination arose from each of these disintegrated empires, most notably in Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East. Poles, Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians, Ukrainians, Romanians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, Montenegrins, and into the Middle Eastern former Ottoman lands, Arabs and Persians further to the East. Within each of these regions were Jews, with Europe’s Jewish communities most concentrated in Eastern Europe (until the Holocaust) where they had settled under the cultural and religious pluralism of the former Poland-Lithuania Commonwealth from the 16th Century onwards.

The Wilsonian ideal of the Paris Peace Conference was to facilitate the expression of national self-determination, but as the array of ethnic groups listed above might suggest, there were multitudes of peoples, often with overlapping territorial claims, to attempt to cater for. This inevitably created what has been termed the “minority problem” of the Paris Peace Conference and League of Nations. While today we conceive of rights at the level of the individual, in the interwar period the unit of expression was entire ethnic groups, conceived as “minority rights”. The concept of universal, individual “human rights” emerged following the Second World War, operationalised as individual rights to freedom from persecution by the state or others in society on grounds of religion, ethnicity, sex, etc. However, in the post-imperial landscape of the aftermath of the First World War, the guarantee of minority rights was of paramount priority, as it was recognised that dissatisfied or oppressed nationalist aspirations could provide a spark that might ignite further conflict.

It was believed that the best safeguard would be, where possible, to ensure that the borders of nation-states were formed around a defined ethnic and cultural majority group, and ethnic minorities that fell within such a territory would be guaranteed legal safety through a series of “Minority Treaties” signed between newly constituted states and the principal Allied powers of the First World War, and enforced by the League of Nations. It was a highly imperfect system, but it was bold and ambitious, as a 2004 paper by historian Mark Mazower attested:

“What was unprecedented in this situation was that the monitoring and guarantee of these provisions was entrusted to a new international organization, the League of Nations, rather than to the Great Powers themselves. It was this system, for the organized international protection of minority rights - not individual human rights as we conceive them - which formed the subject of public concern and discussion in the interwar era...”

Within almost any of these contexts, nothing was straightforward, and the idea that self-determination could be neatly achieved by compiling the people of any relevant ethnic and cultural group into a clearly delineated nation-state ranged from the fanciful to the dangerous. For example, territories of the newly constituted state of Czechoslovakia, the reconstituted Poland, and France with the return of the Alsace-Lorraine regions, all contained substantial German-speaking minorities. In the case of Czechoslovakia, German speakers comprised ~23% of the new state’s population, around ~3-million in total. The League of Nations attempted to resolve such conflicts of territory and cultural or linguistic groups either by decree of lands to be awarded to a specific nation, or in certain cases by holding plebiscites where residents of a contested area could vote for which nation they wished to remain within.

However, the minority problem would always be present, and practically difficult to solve. The primary aim of the peace treaties that emerged from the Paris Peace Conference was to create nationally (i.e., culturally and linguistically) homogenous states, with minorities forming a small proportion of the population. However, the League was not always in the business of border redrawing; achieving majority status for a given ethnic group in a nation-state was often achieved through what was termed “population exchange”. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, signed between the Turkish government as the successor state to the Ottoman Empire, and the Allied powers, resulted in ~1.5million Greek Orthodox and Turkish Muslims being “exchanged” (read: forced deportations) between the two countries. The Treaty of Lausanne also held important implications for Palestine and the Middle East, as under the terms of the treaty Turkey relinquished all claims over the former Ottoman territories, and the peoples of these territories would be provided with the same opportunities for self-determination was was occurring in Europe. This included the Jews as well as the Arab majority populations of former Ottoman territories in the Middle East.

The Jews in many ways posed a unique consideration to this post-war framework of minority rights, because they clearly constituted a distinct cultural and religious group, but were dispersed as a minority throughout multiple European states. In a 2008 paper, the late historian Eric D. Weitz observed that Article 44 of the Berlin Treaty of 1878 had initially attempted to make protection of Jewish rights a matter for international cooperation between European states, but this was so flagrantly and repeatedly violated in Eastern European pogroms so as to render the intent meaningless. The League of Nations was largely ineffective in enforcing minority rights protection; ethnic violence was a constant feature of the interwar landscape of Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Thus, through the interwar period, and definitively by the end of the Holocaust, the premise of the Jews remaining as minorities under the auspices of a non-Jewish majority, and relying on protection from distant international bodies, had for obvious reasons become politically and morally untenable. Indeed, one of the core premises of having a Jewish state was that it would allow Jews to be able to enter and live without having to rely on any other government or the sufferance of a distinct majority ruling population.

This post-war Zeitgeist of minority rights and the political dynamics of realising self-determination provides crucial context to considering a common claim: that Israel is an “illegal” or “illegitimate” state. Neither of these statements are accurate. The emergence of a constituted Jewish nation-state arose from the same processes and international regulatory frameworks that defined this period of history. The Mandates of both Britain and France for the Middle East derived from Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant, with Britain having been awarded the Mandate for Palestine by the terms of the 1920 San Remo Conference. The preamble of the British Mandate stated that “the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect...the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people...”, and that “...recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country...”

That recognition is also critical context, in light of the current trend of superimposing of Americanised progressive academic jargon (“colonialist” or “indigenous”) over the conflict, which ignores the antecedent presence of the Jews in these territories, which preceded Arab conquest of the Levant and remained throughout the currency of the Ottoman Empire. And while the British, as we saw in Part 1, did little to materially assist the Arab population in the Mandate territories, it is ahistorical to view the Mandates as merely a proxy for colonialism, as many are tempted to. They operated within the frameworks of the League of Nations, albeit in a relationship best understood as supervisory, rather than controlling. Nevertheless, the distinction from outright imperialism is important, as summarised by Weitz:

“Despite the best efforts of British and French colonial officials, the mandate system never became simply a cover for imperial power; it was a key institutional expression of the civilizing mission. In fact, the Permanent Mandates Commission (PMC) established by the League functioned much like the Minorities Committees. Both entailed complex systems of international supervision. The covenant required the mandatory power to deliver annual reports to the League Council, which were to be examined by the PMC. The PMC would then “advise the Council on all matters relating to the observance of the mandates.” The PMC sent observers, convened hearings, and issued reports. The various colonial powers had to be cognizant of the reverberations of their actions in the League of Nations and in their relations with other states.”

Further, Article 22 envisaged the Mandates as a temporary administrative process on the ultimate road to self-determination of the peoples within the Mandatory territories. It is important to note that it was this very system which culminated in independent Arab states across the Middle East. There is also evidence that the Arab representatives at Paris, Emir Feisal (subsequently first king of Iraq) in particular, were willing to accept in principle the establishment of a “Jewish home” in the area of the British Mandate, so long as the entire remaining regions under Mandatory administration would become nation-states under Arab sovereignty. For example, Transjordan, which was an autonomous area within the British Mandate, eventually became the independent Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1946. The emergence of a nation-state of Israel should be properly understood as reflecting the interwar process which saw self-determination expressed in numerous states throughout Europe and the Middle East.

To take the rhetoric of “Israel is illegitimate” to its logical conclusion would be to argue that, to name just a few, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, the Baltic States, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, or Hungary, are all “illegitimate” having arose from the same frameworks of the Wilsonian order. The U.N. 1947 Partition Plan envisaged two, independent sovereign states: one Jewish, one Arab. It should also be noted that the partition plan was approved by a vote of U.N. member states, at a time when all other Arab countries formerly under Mandatory administration had achieved independence. The establishment of a Jewish state was thus a matter of international law at the time, consistent with the emphasis on constituting national self-determination as a cultural, ethnic, or religious majority.

This is where we reach an uncomfortable reality, particularly when chants of “from the river to the sea…” ring out on the streets of 2023. What entity exactly are people chanting should be free? Because there has never been a “Palestine”, just as there were no independent Arab countries up until the discharge of the League of Nations Mandates. The only time that specific name was used to denote a specific state was as a province of the Roman Empire (“Syria Palaestina”), and again during the British Mandate, in neither case by reference to any independent entity. Under the Ottoman’s, the region was divided into three administrative districts. More than anything, “Palestine” is an aspiration, one that not even other Arab states appeared keen to subscribe to; when Jordan took possession of the West Bank after the 1948 War, King Abdullah I issued a decree prohibiting the use of the word “Palestine”. Illustrative of the nebulous form of the word, the historian Zachary Foster wrote:

“That’s why many Arabs proclaimed there was no Palestine, only Syria, well into the 1930s and 1940s. They continued to believe the best chance of stopping Zionist immigration was to insist that the object of Zionist desire—Palestine—didn’t even exist… To emphasize the ironies of history, some Zionists and Arabs agreed in the 1930s and 1940s that there was no Palestine. To some Zionists, no Palestine meant the Arabs living in it would apparently be happy moving to Lebanon or Syria. To some Arabs, no Palestine meant the British might hand over the country to Arabs in Damascus, Amman, Beirut or Cairo rather than Zionists in Jerusalem. Few people used the phrase to unconsciously describe any place at all.”

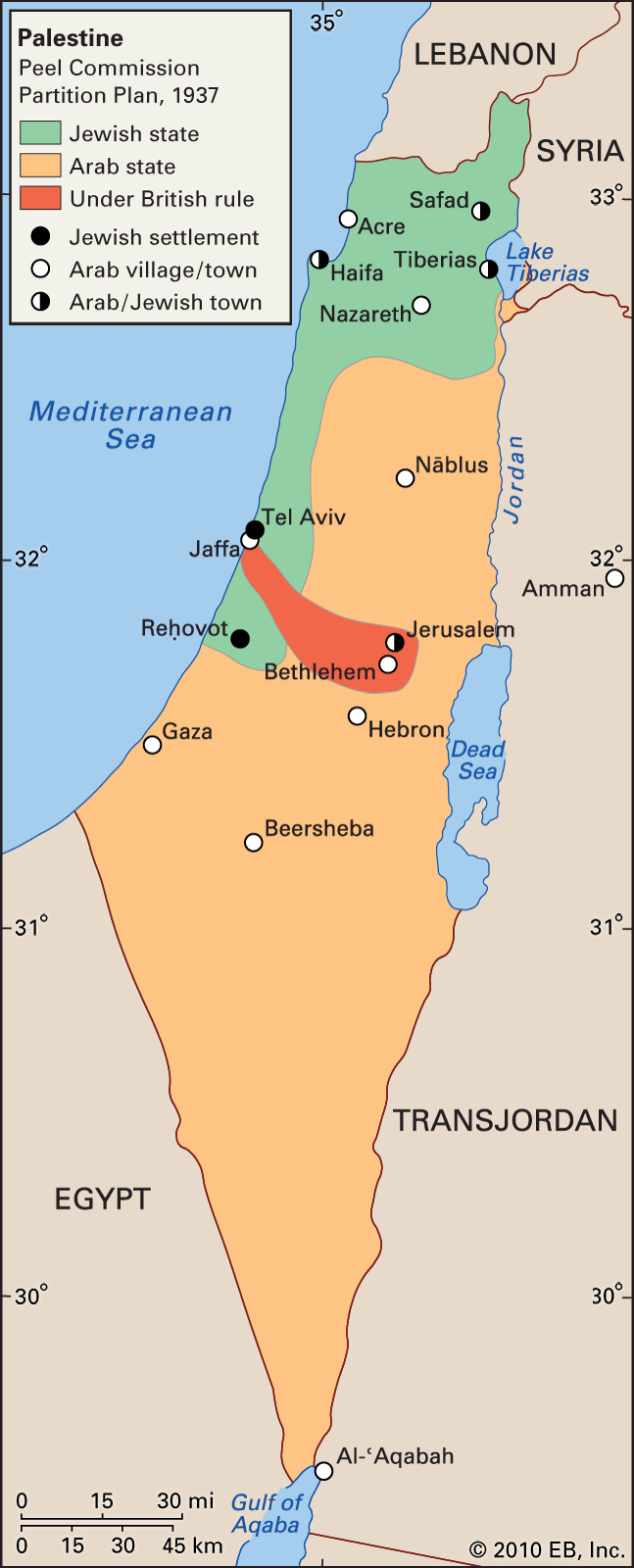

The uncomfortable reality is also extended by the fact that when the aspiration of an independent Arab state of “Palestine” was presented as a determination, the opportunity was rejected. The 1937 Peel Commission Plan proposed under the British Mandate would have provided an independent Arab Palestine of far greater territorial size than any subsequent proposal (see the map, below); this was rejected. The Arabs in Palestine could have chosen to declare independence based on the 1947 Partition Plan, which again would have yielded a more generous state in territorial terms than they are even likely to achieve at this point. They rejected the opportunity afforded by the 1947 Partition Plan. And they rejected the Camp David proposals from Ehud Barak which would have provided a contiguous Palestinian state with ~95% of the West Bank (see Part 1).

Availing of any of these opportunities would have added another Arab sovereign state to the region. And despite whatever failings of the Arab community in the Palestinian Mandate we could point to (as described in Part1), the reality is that ~80% of the former British Mandate territories were assigned to the control of independent Arab nations. This is the scenario that Emir Feisal had desired, reflected in the official records of the Paris Peace Conference:

“Palestine, for its universal character, he left on one side for the mutual consideration of all parties interested. With this exception, he asked for the independence of the Arabic areas enumerated in his memorandum.”

Ultimately, the Arabs in Palestine, and the Arab world more generally, became increasingly hostile to the establishment of a Jewish state, and have rejected the very principle of Jewish self-determination ever since, despite the fact that Arab self-determination had ultimately been achieved over the remainder of the region. In fact, the rejections of several opportunities for Arab Palestinian self-determination over the years is an expression of the rejection of Jewish self-determination; a rejection in principle of the right of the Jewish people to exist in a state of their own.

This distinction is important; Palestinian self-determination has only been expressed in terms of Israel’s non-existence. The Arab countries openly declared to the U.N. that they would go to war to prevent the Partition Plan being implemented. Israel cannot be blamed for the fact that the opportunity for an independent Arab Palestine, in which Arab’s would have been free to constitute their own Palestinian Arab nation, was not taken in 1937, 1947, or 2001. In a memorandum by a Jewish-American group published in September 1947, in which most of the proposals had already been adopted by the U.N., the authors stated in their conclusion:

“In the spirit of compromise, the Jewish Agency in February 1947 expressed its willingness to accede to a partition of Palestine and the establishment there of a viable Jewish state in an adequate area of the country. This proposal would at least bring about finality to the present impossible situation without ignoring Jewish needs and sacrificing Jewish rights altogether. A fair partition will satisfy in reasonable measure the aspirations of both the Jewish and the non-Jewish populations of Palestine.”

This was the solution before a “two-state solution” became an implacable contemporary shibboleth. It should also be noted that the surrounding independent Arab nations have never had any interest in incorporating any of the Palestinian territories into a larger Arab state; their sole interest has been the eradication of Israel. Thus, portraying Israel’s existence as “illegitimate” or “illegal” ignores not only the frameworks, supported by the community of the League of Nations followed by the U.N., which brought about Jewish self-determination, it sweeps under the rug the illegality of the surrounding independent Arab states launching three consecutive wars of annihilation against the Jewish state.

Not only does Israel have the legitimate right to exist, a self-determined Jewish state constitutes a moral imperative, confirmed by centuries of evidence that Jews should never be expected to live as a minority relying on the forebearance of another majority people for their safety and dignity. Their historical presence and religious connections to the lands in the region of Palestine has been accepted by every major commission of inquiry into the dilemma of self-determination in the region, from the Peel Commission to the submissions for the U.N. Partition Plan. And the recent explosion of anti-Semitism, from a pro-Hamas rally in Australia chanting “gas the Jews; gas the Jews”, to American college kids hunting down Jewish students, to Leftist useful idiots applying their tired “social justice” language soup to excuse, justify, or simply delight in the grotesque pogrom of October 7th, have done everything to affirm precisely why a Jewish state is a moral and practical imperative.

Asymmetry Within and Without

The theme of asymmetry permeates the territorial, military, geopolitical, and social factors related to the conflict, and thus provides a useful concept as an organising theme to think through some of its extant realities. There are several sources of asymmetry we can look to: Israel in relation to its position as an independent Jewish state; Israel in relation to the Palestinian people, and to their representatives; Israel in relation to the U.S. and wider Western world; and the Israeli political Left in relation to Right. These are not discreet considerations, and each overlap and intertwine to create the realities that currently exist on the ground.

An appropriate point of departure is the foundation of Israel, given that it is tempting to view the balance of power in the region solely through a contemporary lens in which Israel is a highly militarised power. But this itself is an endpoint of a state founded on literally little more than sand and hope and faced immediately with successive military attempts by other independent Arab states to wipe Israel off the map. Those Arab armies were backed with Soviet arms and equipment, although nevertheless characterised by incompetence and defeated by a numerically inferior force. Israel was born fighting for its life with borders entirely surrounded by hostile invading states.

It is difficult to think of any historical comparison to this asymmetry. While China flexes its muscles over taking Taiwan, this is not an expression of wanting to wipe the Taiwanese people out of existence, but expressed as reunification of one people under one country (however wrong this may be). Putin’s war in Ukraine has been expressed in exterminatory terms, but Ukraine is not engulfed by Russia geopolitically and has not had to fight multiple wars since 1991 to survive as an independent nation of Ukrainians. And insofar as a profound territorial, social, and political asymmetry exists as between Israel and Palestinian Arabs (discussed further below), the role of the surrounding Arab states in shaping the fate of their supposed brethren (again see Part 1) is always swept under the rug in favour of a specific narrative about Israel.

Israel didn’t launch war in 1948, in 1967, or in 1973, and any clear analysis of the period from 1948 demonstrates that the principal source of military aggression has been the Arab states, and since the 1980’s paramilitary violence by proxies of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The two earliest wars of aggression against Israel have played directly on the fates of the Palestinians; the 1948 War precipitated the Nakba, while the 1967 War precipitated the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. It is likely that Israel would have pursued a Nakba-esque forced expulsion at this time anyway, given the prevalence of “population exchange” and legality thereof established by Lausanne, in order to create a state with a large Jewish majority. And while Israel is primarily responsible for the day to day plight of Palestinians in these territories since 1967 (with the exception of Gaza after withdrawal in 2005 and Hamas seizing power in 2007), it is too convenient for contemporary narratives to absolve or ignore the proximate role of the Arab states in shaping the fate of Palestinian Arabs. And in no scenario have the Arab countries been helpful in proposing any territorial solutions, again reflective of a fundamental issue at the core of this conflict: that acceptance of an Israel that is entitled to exist, and exist free from threat of violence, is rejected.

Israel has been surrounded for its existence not merely by countries that desire territorial acquisition, but the eradication of the people within her borders. In the contemporary pincer, there is Hezbollah (Islamic Republic proxy) to the north, Hamas (Islamic Republic proxy) to the south, the Islamic Republic itself within striking range, and the Houthis (Islamic Republic proxy) in Yemen also within ballistic missile range. It is helpful to consider the seminal charters of the Palestinian political and paramilitary movements to emphasise this point, because the intent is clear and unambiguously expressed in writing. Both the original 1964 Palestinian National Covenant, which birthed the PLO, and its amended 1967 version, denied the right of Israel to exist (these articles were eventually nullified by Arafat and the PLO as part of the Oslo Accords). The Hamas Charter goes even further, linking Palestinian nationalism to Islamist fundamentalism, and calls explicitly not only for the elimination of Israel, but specifies a duty to kill Jews. Article Seven of the Hamas Charter declares its universality of its movement and “...encouragement of its Jihad...”, and concludes:

“The prophet, prayer and peace be upon him, said: The time will not come until Muslims will fight the Jews (and kill them); until Jews hide behind rocks and trees, which will cry: O Muslim! there is a Jew hiding behind me, come on and kill him!”

Jews in American universities are currently having to hide in libraries from Hamas’ new Western useful idiots, and while not a rock or tree as specified by the prophet, must surely be to Hamas’ satisfaction. Article Six of the Charter states that Hamas “...strives to raise the banner of Allah over every inch of Palestine.” You know, “from the river to sea” and all that. Although it is entirely correct to state that Hamas and its reign in Gaza is distinct to the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, it should also be noted that Hamas reject any other representatives of the Palestinian people as not sufficiently committed to Islam (Article 27). Hamas are, so long as they exist, irreconcilable to the prospect of Israel’s existence, and therefore to any possible independent Palestinian state that exists alongside an independent Israel. However, despite the deeply traumatic impacts that the horrors of October 7th unleashed on the Jewish psyche, there is no conceivable way that Hamas or Hezbollah could militarily defeat the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF), particularly given that the U.S. bolsters the asymmetry of military power which Israel can project. Yet sitting behind this opposition to any solution other than the eradication of Israel is the Islamic Republic of Iran, for whom maintaining a state of constant threat and instability with Hezbollah in South Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza, is part of the grand design of the Islamic Republic to destabilise the region, continue to cement their own regional hegemony, and ultimately, eliminate Israel.

It is important to note, however, that the legitimation of a state’s right to exist, as Israel has, is not a carte blanche for a state - any state - to act with impunity. In relation to each of these territorial, geopolitical, military and social factors, there is a profound asymmetry between Israel and the lives of Jews in Israel, and the Palestinians in the occupied territories. In territorial terms, the period from occupation following the 1967 War has been characterised by constant and incremental encroachments into Palestinian lands in the West Bank, using declarations of “military land” or “state land” that attempt to circumvent the illegality of seizing lands under Palestinian ownership. This has intensified in the past decade under increasingly Right-wing Israeli governments which, owing to the parliamentary system, contain small fringe far-Right parties representing settler and religious extremist interests in coalition with Likud. The intensification has been characterised by Israeli citizen settler armed violence against Palestinians in their homes, combined with blocking the ability of Palestinian farmers to graze livestock, forcing Palestinians off the land. The armed settlers act with impunity under the watchful gun barrels of the IDF, and retrospective declarations of “legality” by the Israeli courts of new Jewish settlements. That impunity extends to unlawful killing of Palestinians, a crime which is met with shoulder-shrugs and waved off.

This territorial asymmetry was exacerbated by the Oslo Accords, which divided the West Bank into three “Areas”: Areas A and B, nominally under the control of the Palestinian Authority, and Area C which is under Israeli control (the map below from the Israeli human rights group, B’Tselem, illustrates the areas. Area C is under Jewish control; blue triangles denote Jewish settlements; the brown areas are under varying degrees of Palestinian control. As Area C comprises ~60% of the West Bank, the extant reality is that the West Bank is not really within Palestinian ownership or control, and a de facto annexation has been steadily occurring as the tacit government policy of the Israeli Right.

This territorial asymmetry feeds directly into the potential for conflict resolution, given that for Israel to agree to the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state per the offer of Ehud Barak in 2000, i.e., ~95% of the West Bank to Palestine and the establishment of a contiguous Palestinian state, would require the political (and possibly military) will to remove all Jewish settlers and return them to Israel. The settler and religious nationalist response to the withdrawal of Israeli settlements from Gaza in 2005 provides a recent precedent for how this might be received. Given that, in biblical terms, the West Bank (or “Judea and Samaria”) is far more consequential to the Jewish religious extremists and settlers, any withdrawal could be a political, social, and potentially military disaster for any Israeli government.

This is not merely territorial asymmetry, but social and political. The Palestinians in the occupied territories lack political representation in the nation that dictates their lives, lack due process (Palestinians are tried in Israeli military courts in the West Bank), freedom of movement and civic rights, property rights, and the basic recognition of human dignity which forms a central pillar of the Western liberal ideal. For example, as documented by B’Tselem, Israeli policy utilises three pretexts to demolish Palestinian property: unlawful construction, military purposes, and punishment. These pretexts have, collectively, resulted in the destruction of homes of ~23,500 Palestinians in the West Bank over the past decade. The families rendered homeless by these policies have no due process for redress under Israeli law. Conversely, Jewish citizens in the West Bank are afforded all of the civic rights and benefits as they would receive in Israel. Policies of collective punishment have been routine, including mass curfews, cutting off electricity, road closures and blockades. Thus, the situation is that of military occupation in character, and one of dispossession and de facto annexation in practice.

There is a wider asymmetry in the position of Israel as the beneficiary of a U.S. carte blanche, in the form of the American veto in the U.N. security council, to act with a guarantee of impunity against any potential international interjection (over 50% of all U.S. vetoes have been applied on behalf of Israel). This includes a resolution to declare Israeli settlements established since 1967 as illegal, which they are as a matter of international law. The denial of civic and human rights to Palestinians in the occupied territories is not only confined to their status as people under military occupation; it illustrates that the post-1967 occupation is not merely for military necessity (it may once have been considered as such), but a socio-political project of “divide and conquer”.

It holds implications for the potential ultimate resolution of the territorial asymmetry, i.e, of Palestinian statehood on the 1967 lines, reaffirmed as recently as 2016 in U.N. Security Council Resolution 2334, which emphasised that the Council “will not recognise any changes to the 4 June 1967 lines, including with regard to Jerusalem, other than those agreed by the parties through negotiations.” Yet in the period between the issue of the Resolution and 2021, the number of Israeli settlers increased from 400,000 to 475,000. A 2021 press release from U.N. Special Rapporteur for the occupied territories, Michael Lynk, stated:

“Without decisive international intervention to impose accountability upon an unaccountable occupation, there is no hope that the Palestinian right to self-determination and an end to the conflict will be realized anytime in the foreseeable future.”

No decisive accountability will be forthcoming, as the U.N. and the “international community” are rendered toothless in their capacity to enforce accountability over the military occupation by virtue of unconditional U.S. support. Paradoxically, U.S. support is also required given the looming menace of the Islamic Republic in the region, and over Israel. This dual asymmetry means that the U.S. is simultaneously best positioned to directly pressure Israeli policy, and the most unwilling country to do so. To quote Dahlia Scheindlin:

“Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories was never likable, but its critics’ biggest mistake was believing that it was unsustainable.”

However, the political asymmetry is not entirely unilateral. Assume for hypothetical purposes that Israel were ready and willing to agree to a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders this minute: with whom or what are they negotiating to achieve this outcome? It most certainly isn’t Hamas, which ultimately leaves the PA, but the PA are disliked by Palestinians in the West Bank and no longer have any credible power as a representative of the Palestinian people or their interests. This power vacuum is crippling to legitimate Palestinian aspirations for statehood, leaving their representation mired incompetence and corruption on the one hand (the PA) and an Islamist death-cult on the other (Hamas). The movements of the wider Palestinian diaspora, and the international supporters of Palestinian statehood along 1967 lines, are disparate and fragmented, but more importantly, exert no material bearing on the trajectory of Israeli policies in the occupied territories. If we step back from the hypothetical to the extant reality, which is that the Israeli Right has no interest in any solution other than annexation of the West Bank, the grim reality is that despite all of the “international communities” overtures, there are no serious partners for peace to be found on either side of this divide in 2023. The political movement that holds sway in Israel is dominated by settler and religious nationalist expansionists interests, while - at least pending the outcome of this war - the Palestinians have been defined by an irrelevant PA and Islamist fundamentalist group willing death to all Jews.

This is not a promising situation overall, and brings us to a final asymmetry that is perhaps the most important for any genuine peace and Palestinian statehood: the disintegration of the Israeli Left and dominance of the Right. As we noted in Part 1, the collapse of the Clinton-era peace proposals and Ehud Barak’s offer to Arafat, following which Arafat triggered the Second Intifada, marked the start of the erosion of the Israeli Left which had operated on the premise of “land for peace”. The Labor Party that dominated Israeli government for the first two decades of the state’s existence was reduced to just four seats in the November 2022 election; the other player on the Left, Meretz, didn’t even pass the electoral threshold (~2%) to gain a seat. And despite the fact that the Right were in firm power for the pogrom of October 7th, the Right are heaping blame on the Left as the side of the political spectrum historically committed to the two-state solution, seen as coddling the Palestinians. The Israeli Left in the interim from the turn of the century has thus engaged in cognitive dissonance to separate Israeli democracy from the occupied territories. As the journalist Nathan Thrall has documented, assuming that Israel proper and the West Bank are separate regimes allows the Israeli Left to operate under an illusion (of its own making) that Israel is a democracy committed to human rights and liberal democratic values, while the problems of the occupation are something that occur beyond the state, and can be condemned at comfortable arms length. Per Thrall:

“Diplomats and well-meaning anti-occupation groups greet every new act of Israeli expansion with dire warnings that it will be a ‘fatal blow’ to the two-state solution, that ‘the window is closing’ for Palestinian statehood and that now, on the eve of this latest takeover, it is ‘five minutes to midnight’ for the prospect of peace. Countless alarms of this kind have been rung during the past two decades. Each was supposed to convince Israel, the US, Europe and the rest of the world of the need to stop or at least slow Israel’s de facto annexation. But they have had the opposite effect: demonstrating that it will always be five minutes to midnight.”

Realpolitik Endpoints

Much of our interpretation of the asymmetries inherent in this conflict relies on our assumptions, or wishful thinking, with regard to the “two-state solution”. It would be hopeful to think in such terms, indeed it remains the only viable, legitimate solution to the conflict. But you’ve entered the wrong conflict to study for signs of hope; there is none around, no discernible light. The fact that the situation on the ground is, and has been, changing faster than the “international community” can respond to further highlights that there is no real prospect, at least based on the status quo ante, of the “international community” bringing anything but its own hapless declarations and condemnations to the table.

The most important extant reality is one for which the realpolitik conclusion is, unfortunately, inevitable; that the Israeli Right, pending a political miracle, will continue to pursue de facto annexation and there is simply no two-state, or any state, solution that the Israeli Right is willing to offer. Even if Hamas ceased to exist, the Palestinians renounced all violence, and they came to the table and said, “1967 borders it is and Israel has the right to exist in peace”, the majority of the land is no longer on offer. The situation is exacerbated by the reality that Israel has small, dangerous men in power, and small men only think of how they can convey a strong arm. And there are no functioning remnants of the Zionist Left around in Israeli politics to wind the clock again and resume the hope for a legitimate peace based on the historic two-state solution.

Israel has the moral licence to respond to the worst massacre of the Jewish people in one day since the Holocaust. How it responds and questions of “proportionality”, we’ll leave to Part 4. But what appears clear is that the Netanyahu government has no discernible aims other than destroying Hamas, and even this is a fantasy objective given what we’ve learned from 20-years of America fighting non-state Islamist fundamentalism. What comes next? What does “after Hamas” in Gaza look like? Where is any functioning Palestinian leadership? Where is the road back for the Israeli Left?

So here we are; the hands of the clock are stuck at five minutes to midnight. We know this time; it is a time of monsters.

This is a terrific summary, Alan.

Everyone should read this.

Hopefully part 3 includes the USA's role and more about UN failure.