Tying the Gordian Knot: the Historical Entangling of Israel and Palestine

Part 1 of attempting to make sense of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

To most of us watching the latest act in the macabre tragedy of the Middle East unfold, the poisoned well of our information ecosystems exacerbates any capacity for reason or understanding. To much of the internet, the events of and subsequent to October 7th seem to be little more than The Current Thing, a chance to don a metaphorical jersey and rush into the frontlines of the virtual morality play. Behind that display is a perpetuating cycle of death and destruction that is hard to fathom.

As with most 3am Thoughts on contemporary geopolitics, I started writing this in response to current events, which is a futile exercise absent the historical trajectories that have brought Israel and Palestine to this point. Combining both the historical discourse and perspectives on current events was, however, becoming more like a monograph than an essay, so I’ve separated them into four parts. This first part will deal with the entangled Gordian Knot of history.

It is always helpful to write with someone in mind. That avatar is someone who is bombarded with polarising outrage on their social media feeds and sees headlines, like the recent hospital explosion, changing by the day, and would like to perhaps come to their own position without being herded to “take a stand” or “condemn”, and I’m assuming this person doesn’t need to be told that there are no scales upon which to weigh the value of dead children.

I am also conscious this is a topic for which it is almost impossible to say anything perceived as uniformly accurate or representative; if this is something deeply personal to you through ethnicity, religion, or kinship, know that I’ve sought to approach this with the principles of intellectual honesty and epistemic humility at heart. This will not, and could not, cover every nook and cranny, and may seem teleological in part by the necessity of forming an understandable historical narrative: these faults are mine. Now, with those caveats...

Two Empires, Two Peoples, and a Promised Nation: A History to 1948

The historian and journalist Tom Segev described a cemetery on the slopes of Mount Zion which was consecrated in 1840; it contains epitaphs in Arabic, Hebrew, German, Greek, and English. At this time in the first half of the 19th Century this region of Palestine was a backwater of the Ottoman Empire, of which it had formed a part since the conquest of Selim I in the early 1500’s. Prior to the rule of the Ottoman’s, the region had formed part of the Abbasid Caliphate, initially united under Islam in a period over the 8th to 9th Centuries. Before that, Palestine was a hot potato given its strategic location as the bridge of Africa into Arabia, at times under the rule of the Roman Empire, Alexander the Great, the Persian Empire, the Babylonians, and back to the Israelites in the early Iron Age.

However, by the turn of the 20th Century, and typical to the cultural infusions and communitarianism of the Ottoman Empire, Palestine was attracting a cosmopolitan diaspora from all over Europe, a majority of which were Jewish immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe, in addition to Arab immigrants from other Middle Eastern states and Persia. Jerusalem housed pockets of Germans and Americans, Russians and Italians. This diaspora existed as minorities relative to the majority population of the region, the Palestinian Arabs, comprised of both the majority Muslim Arabs in addition to Christian Arabs. And it is important to emphasise that while the Ottoman Empire may have facilitated multiculturalism, it was still an empire and Arab nationalism bubbled under the surface.

As it pertains to Palestine under the Ottomans, however, so too did the aspirations of other peoples in the region, in particular the Jews. Segev describes that many of the Jewish population present in Palestine prior to the First Aliyah, the wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine following the Russian Pogroms against Jews in 1881-1882, were predominantly ultra-Orthodox and rejected the secular principles of the early Zionists. Nevertheless, Russian anti-Semitism served to bolster the Zionist cause once again with further pogroms between 1903-1906, which precipitated the Second Aliyah in the decade up to the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

The Second Aliyah was also notable not only for the composition of the new Jewish arrivals, who were predominantly Russian, but the socio-political views they brought with them, which were socialist. This period saw the establishment of the kibbutz in 1909 based on these collectivist principles, and the establishment of the Ha-Shomer, a defence group that served as the forerunner to the Haganah, the Jewish militia established in 1920 under the British Mandate in Palestine. Their Russian origins were evident in the description of the Ha-Shomer by Hirsh Goodman, who described how they “...looked and behaved like Cossacks.”

This period saw several successes for the Jews under the auspices of the Ottomans, who permitted the establishment of Jewish agricultural towns settled with the immigration of tens of thousands of Jews. The Ottomans also allowed for the Jews to purchase land, and permitted the establishment of an independent Hebrew school system. The Ottoman Empire was the only glue holding the aspirations of the peoples of Palestine together, however, and the outbreak of war in 1914 altered the course of the Middle East, just as it altered the course of Europe. Arab nationalism was not a phenomenon localised to Palestine, and existed across the Arab world, but for the ~700,000 Arabs in Palestine before the outbreak of war, the Ottoman decision to join the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1914 would link the fate of the Empire to the outcome of the war.

The British ended up doing what they did best in the declining years of empire; over-promising, duplicity, and under-delivering. In 1915, Sir Henry MacMahon, the British High Commission in Egypt, promised Arab independence to the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein ibn Ali, in return for Arab support to defeat the Ottomans. The extent of the promise encompassed a full, unified Arab kingdom including Palestine, Syria, Iraq, and the Arab Peninsula. The Sharif duly obliged and launched the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottomans beginning in June 1916. However, the British were simultaneously negotiating with France for what became the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, which divided the post-war Middle East into five separate administrative regions or “mandates” between the British and French. Despite this, the Arabs viewed the promise of MacMahon as a promise to be kept, and acted accordingly in rising up against the Ottomans.

In 1917, two seismic events occurred one month apart to the day. On the 9th November, the Balfour Declaration was published, bearing the name of the then British Foreign Secretary, Arthur James Balfour, which provided the first official articulation of British support for the establishment of a Jewish “national home” in Palestine. Segev highlights the cautious wording of the document, which did not state that Palestine would become the national home of the Jews, but that a national home would be established in Palestine, i.e., in part of it. This undertaking was also conditional on nothing being done, in this establishment, to prejudice the civil and religious rights of the Palestinian Arabs. One month later, on the 9th December, the first British soldiers set foot in Jerusalem, after a slogging campaign that left Egypt in spring of 1917, and required three battles to take Gaza. The Turks were defeated, and Palestine passed from the hands of the Ottoman Empire into the hands of the British Empire.

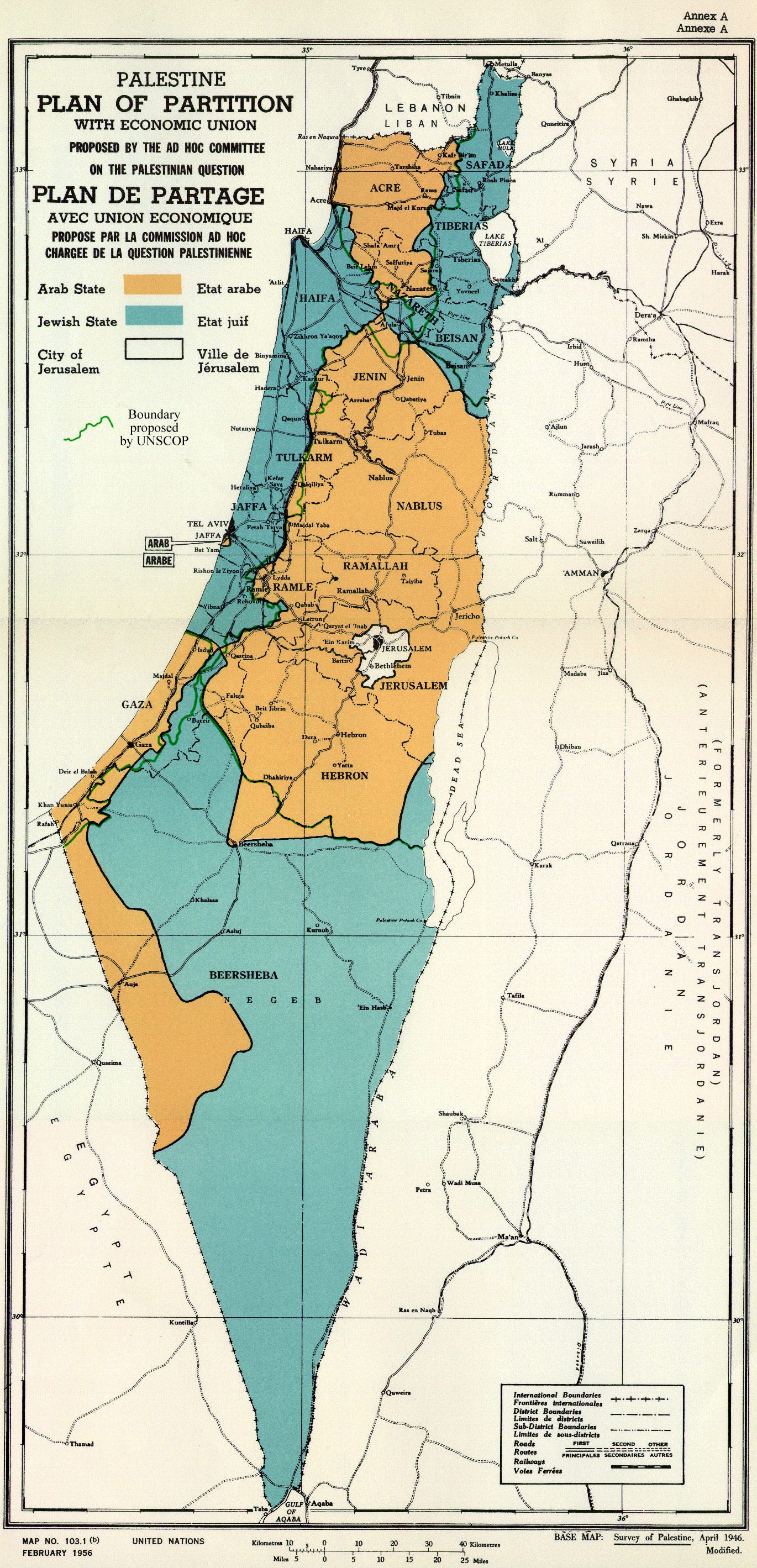

The aspirations of two national movements, the Arabs and Jews in Palestine, passed with this transition of imperial power. Typical to British imperial form, just as they were at the time in Ireland and would subsequently do in India, the British were trying to play both sides of a sectarian struggle over territory. It is important to note that Palestine denotes a region, the precise geographic delineations of which have altered over time relative to the political status of the region. There has never been, at any point in history, a formal state or unified independent polity with that name. When the British Mandate in Palestine was formally established in 1920, the primary aim of the British was keeping the French, who controlled Syria and Lebanon, from any further territorial gains in the Middle East, protecting oil sources, and guarding the Suez Canal. The Mandate formally included territory east of the Jordan River (see the map below, for illustration), known as the Emirate of Transjordan, which ultimately became the independent nation of the Hashimite Kingdom of Jordan in 1946.

Yet the lands to the west of the Jordan River would provide the British with a 20-year headache, one in which their presiding over an increasingly violent sectarian conflict earned Palestine a reputation as Britain’s “second Ireland”, with colonial administrators comparing the Jews in Palestine to Ulster’s Protestants. Segev describes how David Ben-Gurion, who would later become Israel’s first prime minister, feared this comparison would harm the Zionist movement by identifying Palestine as a “second Ireland, a land of anarchy and terror.” Yet from the late 1920s until the outbreak of the Second World War, “a land of anarchy and terror” was precisely what the British were presiding over.

Under the early years of the British Mandate, both the Arabs and Jews believed their aspirations for statehood and independence would be realised under the British. After all, both had been promised a nation. But the wind blew more in one direction, and in response to the increasing agitation of Arab nationalists, British support tilted distinctly to the Jews in Palestine. Segev summarises the Mandate period:

“The British kept their promise to the Zionists. They opened up the country to mass Jewish immigration; by 1948, the Jewish population had increased by more than tenfold. The Jews were permitted to purchase land, develop agriculture, and establish industries and banks. The British allowed them to set up hundreds of settlements, including several towns. They created a school system and an army; they had political leadership and elected institutions; and with the help of all of these they in the end defeated the Arabs, all under British sponsorship, all in the wake of that promise of 1917.”

In temporal sequence, however, this tenfold increase in the Jewish population by 1948 was a relative increase, because one of the most grotesque events in history had occurred immediately prior: the Shoah, or what we term the Holocaust. In 1933, the National Socialists came to power in Germany and commenced a state-coordinated program of dispossession that stripped the Jews in Germany of basic rights, and property, and subjected the community to constant violence. This served only as the prelude to the subsequent European-wide program of extermination which began in earnest in 1941 on the Eastern Front with death squads dealing in manual slaughter; areas of the Baltic were declared “Judenfrei” (“free of Jews”) in 1942. The concentration camps, using gas chambers and ovens, provided a more “efficient” method of extermination for the Nazis; by 1945, 6 million Jews, two-thirds of Europe’s pre-war Jewish population, had been murdered.

However, while horrified by the Holocaust, neither Britain, America, or any other Allied nation were particularly enthusiastic about taking Jewish refugees from the displaced persons camps that sprung up to house and process survivors. An infamous scene in Schindler’s List, rumoured to be based on a true encounter, summed up the post-war sentiment; a Russian calvary officer says to the gathered Auschwitz survivors: “Don’t go east, that’s for sure. They hate you there. I wouldn’t go west either, if I were you.” Over a five-year period following the Nazis coming to power, some ~175,000 Jewish refugees arrived from Europe, bolstering the total Jewish population to just under half-a-million.

In May 1939, the British had published a policy document, “the White Paper”, which committed to the establishment of a binational state in Palestine within a decade. The White Paper restricted new Jewish immigration to Palestine at 75,000 over the following 5-years, and limited the transfer of Arab property to Jewish ownership. With the war being waged, however, ways were sought to get around the immigration quotas in the British White Paper. Segev describes a total of 60 journeys by illegal immigrant ships operating from Palestine to the port of Constanta in Romania, which brought in about 20,000 immigrants without quote permits from the British. Another 40,0000 arrived under the quota system, although estimates vary as to the precise number of Jews who made it to Palestine from Europe during the war years, Segev suggests that just over the 75,000 quota had arrived by December 1944.

By the end of the war, the situation on the ground had intensified, and the British faced terrorist activities from both Jewish and Arab groups. After 19 British commissions on the competing Arab-Jewish aspirations in Palestine, the British handed over to dispute to the UN, which proposed two separate states for each people. This process culminated in the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947 that gave birth to a Jewish state; the precise delineations of the UN proposal is shown in the map, below (the land of the proposed Arab state in orange, and the Jewish state in blue).

One of the proposed states, Israel, formally declared independence on the 15th May 1948 on the basis of the UN Partition plan. The very next day, the Arab states of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq, declared war on Israel.

Drawing Lines in the Sand: A History from 1948 to 1973

The Arab states had a clear intent in 1948: drive the newly declared independent state of Israel into the sea, and out of existence. What they were not expecting, however, was to run up against a well-trained and led Jewish military and cohesive national Jewish unity. This cohesion also reflected the British influence on the balance of power in the Mandate years, as Segev writes:

“...after thirty years of ruling Palestine, the British had still not instituted compulsory school attendance...only three out of every ten Arabs went to school. The other seven, mostly in the villages, grew up illiterate. They were a lost generation. The result of this loss for the Arab community was catastrophic. A nationwide system of education would have forged national cohesion. But the war of 1948 found the Arabs rent by regional, social, and economic divisions... The Hebrew education system, by contrast, formed the Jews into a national community, prepared them for their war of independence, and led them to victory. Had Britain limited its support for Zionism to nothing other than perpetuating Arab illiteracy, His Majesty's Government could still claim to have kept the promise enshrined in the Balfour Declaration.”

The period before and over the war had seen the consolidation of what would become the Israeli Defence Forces. In ‘The Anatomy of Israel's Survival’, Hirsh Goodman notes that by 1936 the Haganah could field a force of ~10,000 men. During the war, the British had formed and trained a Jewish commando unit known as the Palmach, while after the war many of the ~30,000 Jews who had served in the British military, including Royal Air Force pilots, returned to join the ranks of a budding military force. Goodman describes the 1948 war thus:

“The Arabs initially invaded with a combined force of 23,000, commanded by four different general staffs, without a unified plan other than to cross the border, find Jews wherever they could, and push them back into the sea. They had not prepared for this war, totally underestimated the Jews, and were confident that the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians inside what the Jews called Israel would rise up with them, like an unstoppable fifth column, or fifth force. They were wrong on all counts.”

The consequences of the 1948 war became known as the Nakba (“catastrophe”) to the Palestinians, resulting in ~750,000 of the ~950,000 Palestinians in the territories of newly established Israel either fleeing the fighting or being expelled at gunpoint. The war was brought to an end by the 1949 Armistice Agreement between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria; Egypt concluded the war in control of Gaza, while the territory of the West Bank fell to Jordan. Egypt established somewhat of a precedent; operating Gaza as an “open-air prison”, imposing curfews and restricting movement of Palestinians confined to refugee camps. The Palestinians who fled to Jordan largely ended up in the West Bank, which proved to be a temporary respite. Jordan would go on to expel tens of thousands of Palestinians after the so-called “Black September” civil war between the Yasser Arafat-led Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Jordanian King Hussein's state forces. Within the tentative borders of Israel, Palestinians at the time ostensibly had the same rights as Jews, but in practice faced discrimination and were restricted in access to government.

The 1949 Armistice established “the Green Line”, which now are also referred to as the “1967 line/borders” for reasons we will presently come to. The border is illustrated in the map, below, from the Israeli human rights group, B'Tselem. The 1948 war would have far-reaching implications in terms of the Jewish national psyche, which Goodman describes as strengthening the trauma of the Holocaust; the war claimed the lives of ~1% of the Jewish population in Palestine. The effect of that war was that:

“The survival syndrome permeated every level of society, paranoia was seen as a national value, great freedoms were afforded the security organisations, generals were Israel's soccer stars, and the secret service, the silent heroes of the day. If postwar Jewish survival was forged in the ovens of Hitler, it was galvanised by the 1948 war.”

Two crucial events occurred between 1948 and 1967 that would have profound implications the trajectory of the entanglement: the 1950 Law of Return, and the expulsion of the Jews from Arab countries. The Law of Return offered Israeli citizenship to anyone who was one-eight Jewish, which was the same criteria the Nazis had used to send Jews to the gas chambers, and Jewish immigrants arrived from all over the world. Arab countries, for example Egypt in 1956, formally expelled their Jewish populations, while under threat other Middle Eastern Jews opted to leave long-established Jewish communities, such as Baghdad in Iraq. By 1958, the population of Israel reached 2 million. However, these were not homogenous Jewish populations, and their varying experiences would ultimately influence Israeli politics, in particular those first and second-generation immigrants from Arab countries. Per Goodman:

“Even in Israel there is little real understanding for the trauma faced by the Jews forced to leave Arab lands, of once-aristocratic families, Jews living like pashas and effendis...banished and absorbed by an impoverished nation fighting for its life with very little to give other than the rudimentary supplies for getting by... The Jews of Europe came decimated; the Jews from Arab lands, impoverished, confused, and bitter... It would take twenty years and two wars before their vote would determine the future course of Israel...[capitalising] on their hatred and mistrust of the Arabs who expelled them.”

The two wars in reference were the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The Six Day War began after Egyptian president Abdel Nasser dismissed the UN peacekeeping mission and mobilised forces in the Sinai Peninsula to the south of Israel, and threatened to cut off Israel’s shipping routes through the Tiran Straights. Once again, the forces of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq, combined to form an Arab alliance mobilising against Israel, but their defeat was total. The Israeli air force destroyed most of the air forces of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, by attacking their bases while their forces were grounded; the Israeli ground attack resulted in the capturing of the Sinai from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan.

This victory would define the entanglement and conflict for every year since 1967. Israel was faced with a dilemma of what to do with these newly acquired territories. Voices from the old pre-state Zionist and British Mandate period, led by Ben Gurion, saw the writing on the wall for the implication of Israel having to absorb the Palestinian Arab populations of the West Bank or elsewhere, and recommended that Israel, having made the military point again, return the territories. For others, including the consecutive prime ministers Golda Meir and Menachem Begin, the stunning victory of the Six Day War created a spirit of triumphalism and arrogance, with many - including Begin - seeking the full annexation of these territories.

The compromised solution was in fact a non-solution; maintaining these areas for strategic reasons, in particular the West Bank, but (initially) on the condition of limiting Jewish settlement beyond military requirements. However, the declaration of land in the West Bank as “closed military zones” would become an immediate strategy to deprive available land to Palestinians, with a quarter of the West Bank’s land declared as such between 1967 and 1975. The establishment of civilian settlements on what was privately owned Palestinian lands also began almost immediately after the occupation of the West Bank, and in Gaza. East Jerusalem was fully annexed immediately after the war. The “Green Line”, although technically visible on a map, was politically erased by the steps taken in the aftermath of the 1967 war.

In 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked again, in what became known as the Yom Kippur War, as the attack occurred on a Jewish holy day of October 6th bearing that name. Although initially caught off guard, Israeli forces rallied and again defeated both. For Egypt, the defeat resulted in the ultimate normalisation of diplomatic relations with Israel, and as part of the peace agreement between the nations Israel agreed to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt. Israel retained the Golan Heights and also signed an armistice with Syria the following year. However, neither Egypt nor Jordan appeared to retain interest in the now-occupied Palestinian territories of Gaza and the West Bank. Jordan formally renounced territorial claims in 1988, following the breakdown of negotiations between Israel and Jordan that would have placed the West Bank under Jordanian jurisdiction subject to conditions to guarantee Israel's safety. A formal peace was signed between Israel and Jordan in 1994.

If, in these preceding paragraphs, the Palestinians in the territories occupied after the Six Day War seem to be pawns in an inter-state geopolitical struggle, that is because this is precisely the unfortunate fate they found themselves in. The concept of agency as it relates to the Palestinians is crucial, because while they have retained a degree of agency, agency in their ultimate fate has always been constrained or deprived. The fate of the Palestinians in this period was not merely one being decided by Israel, but by the surrounding Arab states. The PLO had been founded in Cairo in 1964 as an umbrella group which contained several nationalist Palestinian factions, and would eventually be dominated by Arafat’s Fatah party. However, over subsequent years the PLO would, as an independent movement, often find itself at odds with the bilateral (vis-a-vis Israel) or regional interests of Arab states.

We can dispense with one romantic myth; that the wars which Egypt, Jordan, and Syria launched against Israel were some unified mission of Arab solidarity with the Palestinians. In the first instance, they were autonomous states seeking their own territorial gains with the overarching intention of wiping Israel off the map. More particularly, their treatment of the Palestinians as refugees is sufficient evidence to repudiate any idea of higher ideals behind these wars. The reality is that these states - Egypt and Jordan in particular - played as much a part in the dispossession and dislocation of the Palestinians in this period. As the political scientist Dahlia Scheindlin once stated:

“The last time masses of Arab citizens rallied for the Palestinians was never.”

This period had one particularly important overall outcome; those state actors of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, would in subsequent years either sign peace treaties with Israel, or at least step back from the illusion that they could defeat Israel militarily. While they could posture support, the reality is that Israel had succeeded in taming the threat of some immediate neighbours on the border.

Setting the Gordian Knot Aflame: A History from 1973 to Present

This period could be defined by some key characteristics. The first is the shift of Israeli politics to the Right; the second is the emergence of power dynamic struggles within the PLO; the third is the Palestinian “intifadas”, or uprisings, and the attempts at peace agreements over the intervening periods between intifadas. Each of these are, of course, intertwined, but if the preceding sections were describing the tying of the Gordian knot, this is where the knot was doused with petrol and set on fire.

The shift to the Right started with the seed planted by the expulsion of the Jews from the Arab states, a voting bloc ultimately mobilised by Menachem Begin and the party, Likud, in the 1977 election to topple the Labor Party which had held power continually since Israel’s foundation. This shifted the balance of electoral politics away from the socialist/Left-wing principles of the kibbutz movement that characterised the early years of the state. Begin was a firebrand who wanted the annexation of all territories, including “Judea and Samaria” (what Jewish religious nationalists call the West Bank), and who headed what the late political scientist Amos Perlmutter described in a 1982 paper in Foreign Affairs as a “brash, recalcitrant, and pugnacious government whose chief symbol is Defense Minister Ariel (Arik) Sharon...” Perlmutter described their relationship thus:

“Begin, a fanatic and firm believer in the concept of "Eretz Yisrael" (or Complete Israel), a stolid and implacable opponent of any sort of Palestinian national movement, has found the perfect instrument to carry out in vivid action what lies at the core of his rhetoric. Whereas the likes of (Ezer) Weizman and (Moshe) Dayan restrained, modified, and manipulated Begin's instincts, Sharon frees them and carries them to their logical conclusion.”

Perlmutter was writing during the First Lebanon War of 1982. The war was a disaster for Israel, worse for Lebanon, and resulted in the PLO being exiled to Tunisia. South Lebanon had become the operations base for the PLO, from where attacks against Israel were being launched. The initial Israeli response was intended to be limited in scope, however, Sharon pushed for an expansive conflict that ultimately involved Syria and warring Lebanese nationalist factions. Israel would side with Lebanese Christian militias, who massacred thousands of Palestinians and Lebanese Shia refugees in Sabra and Shatila, an event to which the IDF essentially turned a blind eye. The protests in Israel against the government following the massacre were the largest civil protests in Israeli history at the time, and eventually resulted in the dismissal of Sharon and the resignation of Begin.

The rise of the Israeli Right spearheaded by Begin and Likud, and enflamed by Sharon, provided unambiguous indications for the desires of the Right and the increasingly visible religious nationalism, which Permutter's 1982 paper presciently foretold:

“That dream is to annihilate the PLO, douse any vestiges of Palestinian nationalism, crush PLO allies and collaborators in the West Bank, tighten Israel’s grip on the West Bank and eventually force the Palestinians there into Jordan and cripple, if not end, the Palestinian nationalist movement.”

The PLO sought to reassert itself through the First Intifada, which began in December, 1987 at the behest of Arafat’s Fatah, but also a new group within the PLO founded the same year, known as Hamas. A radical Islamist-fundamentalist group, the stated aim of Hamas was, and remains, the eradication of Israel and the death of all Jews. Nevertheless, the First Intifada took the form, overall, of unarmed protests by the Palestinians, but violence erupted over the course of the four year period of unrest, largely youths throwing rocks and, in some cases, Molotov cocktails. More Palestinians were killed by PLO death squads who accused Palestinians of collaborating with Israel, than were killed in violent exchanges with the Israeli military. Conveniently, where it was subsequently shown to the PLO that the suspected collaborator had been innocent of the charge, they were just declared a “martyr”.

However, the First Intifada was also where the court of public opinion started to turn against Israel. Images of ragged kids throwing stones at the heavily-armed might of the IDF reversed the tale of David and Goliath and presented an image the state of Israel not as David, but as Goliath imposing itself on a defenceless and dispossessed Palestinian people. Footage of Israeli soldiers breaking the arms of Palestinian rock-throwing kids didn’t exactly enhance Israel’s global image, but they were merely following the lead of the then-prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, who declared that breaking Palestinian bones was precisely what they would do. Ironically, it would be the same Rabin who ultimately signed the first meaningful attempt at peace and a “two-state solution” a few years later.

The end of the First Intifada in 1993 saw tentative attempts at brokering a peace, held in Oslo, Norway, in 1993. In what became the Oslo Accords, signed under the eye of then U.S. President Bill Clinton, Israel agreed to recognise the PLO as the “representative of the Palestinian people” and allow Arafat to return from exile in Tunisia, while the PLO recognised “the right of the state of Israel to exist in peace and security”. In terms of a potential two-state solution, Oslo proposed the establishment of a Palestinian Authority (PA) to govern in the occupied territories, and an interim timeline during which issues such as the right to return for Palestinian refugees from 1948, precise borders, and Jerusalem, would be ironed out on the road to implementation of Palestinian statehood by 1999. That Palestinian state would theoretically be based on the pre-1967 or “Green Line” borders, subject to some negotiated changes, which de facto had been somewhat reestablished by the First Intifada as a security boundary for Israel.

The prospects for implementation of Oslo were, however, stymied by an increasing volatile shift in Israeli domestic politics and an intransigent Arafat who sought to consolidate his own position within the PA while playing the demographic long-game. Barely after the ink was dry on the Accords, Arafat declared that “the womb of the Palestinian woman” would be the greatest weapon against Israel. But the demographics of Israel had also shifted, and the ascendant religious nationalist movement would express its dismay at the prospect of giving up land for a Palestinian state in the 1995 assassination of the prime minister who signed the Oslo Accords, Yitzhak Rabin, by a Jewish Orthodox fanatic. Goodman describes the stock from which Amir emerged:

“The second- and third-generation settlers, the youngsters, knew nothing of the Green Line, could not tell you where the 1967 boundaries were, and had been brought up and education in a bubble that let little of the outside world creep in, believed that Rabin was giving away their promised birthright, Eretz Yisrael, God's land. When he assassinated Rabin, Amir had enough rabbis backing him to secure a place in heaven had he been killed carrying out his mission.”

Oslo accelerated the process of drawing out the religious nationalist settlers, particularly in the West Bank, into the fore of Israeli politics. This shift in the power dynamic also held implications for the Israeli Left, which operated on the principle of “land for peace”, and placed them squarely at odds with the religious nationalist movements on the Right. Yet the Right itself would also inflame the religious nationalists and settlers through Benjamin Netanyahu's first government, elected in 1996; Netanyahu agreed to withdraw the IDF from Hebron, considered one of the holiest cities for religious Jews, but firmly on Palestinian land in the West Bank. Now, it was also the Right that appeared to be compromising, which pushed the religious nationalist and settler movements further to the Right again. The ripple effects of this shift would culminate in the November 2022 election that brought Netanyahu back to power for the third time, albeit with the most Right-wing and religiously fundamentalist government in Israeli history, and in any contemporary democracy.

Ehud Barak succeeded Netanyahu as prime minister after his first term, and as Netanyahu split the Right, Barak precipitated the fragmentation of the Israeli Left. It is important to note that as an electoral system, Israeli democracy is about as stable as Italy’s, which is to say not at all. Governments have four-year terms of office; most never make it past three. Just 2% of the electorate can return a seat in the Knesset (the Israeli parliament), and beyond the large parties like Likud and Labor, the electoral landscape is dominated by a multiplicity of small parties representing narrow interests, often extreme in the case of the religious and settler Right-wing. Governments are formed with coalitions based on horse-traded promises, before disintegrating over competing interests on core issues, with territory, security, and religion, constant points of contention both within and between the Left-Right political spectrum.

Left Zionism, i.e., the movement on the Israeli Left which supported the establishment of a viable, independent Palestinian state along the “Green Line” borders, was dealt a major blow with the assassination of Rabin. However, it ran out of road under Barak in 2000 at Camp David in another attempt to revive Oslo and implement what became known as the Clinton Parameters. Both Barak and Clinton were on comparatively weaker ground; Clinton coming to the end of his years in office desperately wanting his signature on an Israeli-Palestinian peace and a Nobel Prize, and Barak with another mutinying coalition Israeli government crumbling around him desperately hoping that a deal could salvage his sinking ship. At Camp David, Barak put all his chips in; ~95% of the occupied territories to Palestine and some small land exchanges to ensure a contiguous Palestinian state, and a shared Jerusalem as the capital with Jewish areas remaining with Israel. However, Arafat, while accepting the establishment an independent Palestinian state on the “Green Line” boundaries, would not agree to legitimise Israel’s presence in the remainder of historic Palestine, and required that the 1948 refugees be allowed to return to their homes in those areas of what was now Israel. The reality is that neither Arafat nor the PLO has ever been truly committed to the recognition of Israel’s right to exist, and this reality has underpinned all the false starts and failures in the peace process.

The central principle of the Israeli Left, “land for peace”, had been on the table, and it had come to nought. In rejecting Barak’s proposal and with the so-called “Clinton Parameters”, the Israeli Left fragmented. When Ariel Sharon’s ill-advised trip to Mount Temple that same year resulted in riots, the Second Intifada erupted. But unlike the mainly unarmed First Intifada, the Second Intifada constituted a full-frontal assault against Israel and represented the Islamist-fundamentalist goals of Hamas, who deployed suicide bombers throughout Israel to schools, cafes, and busy neighbourhoods. The carnage and fear of the Second Intifada would also have lasting implications when it ended after four years; the building of the security boundary wall to separate Israel from the West Bank, the lack of trust in the remnants of the Israeli Left, an emboldening of the Right, and the cementing of the prominence of the religious nationalist movements in the political picture. The domestic political dynamics were now firmly against the Palestinians, and settlements in the West Bank continued to expand.

The prominence of the religious settler community came to the fore with the decision by Sharon as prime minister to withdraw from Gaza in 2005. This would have profound consequences. The withdrawal was total, and included the removal of all Israeli settlements in Gaza; even the dead were exhumed from the Jewish cemetery and returned to Israel. However, the sight of the IDF removing Jewish settlers sent alarm bells off in the West Bank settlers, who feared they were watching their impending fate play out. “Judea and Samaria” lies at the core of the biblical narrative of the Israeli settler and religious nationalist movement. Mass protests were organised, spearheaded by religious nationalists, to protest the withdrawal, including a human chain formed from Jerusalem to Gaza, with t-shirts being worn in the colour orange, which became the colour of the anti-withdrawal movement. The ripple effects remain in the vocal presence of settlers on the Israeli Right, which has dominated Israeli electoral politics since. By 2019, just over ~60% of Israeli children were attending religious schools, rather than secular state-run schools. Hirsh Goodman described the importance of the moment:

“The real significance lay in the fact that two of Israel's greatest warriors, Sharon and Ehud Barak, foremost strategists and acknowledged security experts, had both come to the same conclusion from two different spectrums of the political scale: it was vital for Israel's future that the territories be returned, a Palestinian entity established, with the understanding the "we" live here, and "they" live there. The mainstream Labor and Likud view overlapped; experienced heads had come to a common view. This had serious unforeseen consequences: opponents of the removal of the settlements, finding no support for their view in the center [sic], drifted to the extreme fringes, empowering radical parties that were marginal beforehand.”

The other profound consequence of Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza was for the Palestinians. With the PA weak and increasingly seen as self-serving, Hamas initially won parliamentary elections in 2006 before seizing full control of Gaza by defeating Fatah forces loyal to the PA. Their takeover had all the predictable ruthlessness of Islamist fundamentalism, throwing Fatah loyalists off buildings, executing “collaborators”, segregating schools, and implementing “morality policing”. Severed from the PA and the West Bank, Gaza subsequently became a separate entity to the Palestinian cause, with a death cult of terrorists at the helm whose stated aim is death to Jews and the obliteration of Israel. This was always going to be an irreconcilable, and untenable, reality for the ordinary people of Gaza, who are now caught between two ruling powers that will not extend basic civic and human rights to them.

Survival or Democracy?

In the interim, Israel’s domestic political landscape has become more fractured and volatile than perhaps any moment in her history. In 2022, Netanyahu clobbered together a coalition of fringe Right-wing religious nationalists and sought to implement judicial reforms that would remove the ability of the judiciary to have oversight on government, as part of a suite of increasingly authoritarian policies. Israel was convulsed with its largest ever civil society protests against the government and the proposed judicial reforms. Before the pogrom on October 7th, Israeli democracy was fighting for its life.

A common sentiment from Israeli commentators and politicians, particularly on the Left, is that Israel faces a choice between preserving a Jewish state and democracy, but it cannot do both if it holds on to the occupied territories. With the Right and the religious nationalists in the driving seat, and a fragmented ineffectual Left with little trace of Zionist Leftism evident, the chances of Israel surviving as both a Jewish state and democracy appear slim. In order to pursue and expand the former, the latter will become corrupted and implode.

Where we go from here is anyone’s guess, but the trajectory of history outlined above gives us some clues: the bloodshed, rage, and hostility of two deeply traumatised people will continue to play out like a macabre psychodrama. This conflict erodes our moral centre.

Thanks a lot, Alan, for this detailed and comprehensive (if this ‚knot‘ can ever be covered ‚comprehensively‘) essay, really highly appreciated - it is your love and ‚Herzblut‘ for detail and humility that is so much needed in approaching this topic! I‘ve actually studied politics, and the political system of Israel had been one main focus; that said, I seriously learned even more from this essay of yours! Seriously, thank you!

Thank you for describing the complex history with such great detail!