Maybe if we'd season th' immygrants a little or cook thim thurly, they'd go down betther.

Nativism with American Characteristics.

The quote in the title is attributable to “Mr Dooley”, a fictional character and protagonist of political cartoons in America from the 1890s through to the 1920s. “Mr Dooley” was an Irish immigrant from County Roscommon who dispensed his wisdom from his profession as barkeeper-philosopher, a quintessentially Irish role, written in what was intended to be a phonetic Irish dialect and accent by a first-generation Irish-American, Finley Peter Dunne. The full text of that particular sketch read:

‘Well,’ says he, ‘they’re arnychists,’ he says; ‘they don’t assymilate with th’ counthry,’ he says. ‘Maybe th’ counthry’s digestion has gone wrong fr’m too much rich food,’ says I; ‘perhaps now if we’d lave off thryin’ to digest Rockyfellar an’ thry a simple diet like Schwartzmeister, we wudden’t feel th’ effects iv our vittels,’ I says. ‘Maybe if we’d season th’ immygrants a little or cook thim thurly, they’d go down betther,’ I says.

In this sketch, Dunne satirised the virulent discourse and anti-immigration sentiment that ebbed and flowed through American social, cultural, and political life between 1860 and the late 1920s. The tribulations of that period took the Great Depression and the Second World War to quell, with the former instilling a sense of common burden and the latter providing the ultimate test to that refreshed national cohesion and sense of the nation’s self. In this respect, Mr Dooley was reflecting a shift in attitudes, a distinctly different tone to the poet Emma Lazarus, whose 1883 sonnet, ‘The New Colossus’, came to define the “Age of Confidence”, a period through the 1870s to 1890s in which belief in the power of assimilation and of the fundamental role of America as the Promised Land of the “Old World’s” poor and oppressed ran high:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Lazarus’ “tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free” had come in their millions in waves of immigration throughout the 19th Century, particularly from the 1820s onwards, precipitating a century-long ideological convulsion on the definition and meaning of “American”. Between 1840 and 1890, around 15 million immigrants arrived in America, including over four million Germans (mostly in the aftermath of the 1848 revolutions) and three million Irish (mostly during and in the wake of “An Gorta Mór” [the Great Hunger], the Irish Potato Famine of 1845–52), with additional millions from Britain and Scandinavia. The wave from 1890 until the introduction of stringent immigration policy in the 1920s saw an additional 18 million, with four million Italians and ~6-10 million from the myriad peoples of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, mostly Slavs and Jews. Overall, ~80–90% of the mass immigration waves of the 19th and early 20th Centuries were from Europe, and by 1860, most of America’s major cities had a higher proportion of foreign-born residents than at any point since.

But was washing up at Ellis Island enough for these “huddled masses” to be considered “American”, and who defined what it meant to be American?

Nativism with Yankee Blueblood Characteristics

From the 1850s onwards, and coloured by the aftermath of the Civil War, America engaged in an intense soul-searching exercise over those very questions, over the consequences of these mass waves of immigration for American social, political, cultural and economic life: over the very meaning of American identity itself. In contrast to Lazarus’s optimistic, confident expression of America beckoning Europe’s destitute masses to the beacon of liberty, however, a competing ideal of what it meant to be “American” fought against this optimistic vision, characterised as “nativism”.

As the foremost historian of that period, the late John Higham, elucidated in his definitive work, ‘Strangers in the Land’, the nativist vision reflected the dominance of the old Anglo-Saxon elites, religiously and culturally Protestant, temperate in character, politically moderate, uncompromisingly capitalist, and explicitly ethnocentric. Certain core characteristics thus defined the American nativist movement in the period 1850–1925: rabidly anti-Catholic and anti-Papist, anti-radical and anti-socialist, anti-Semitic, and anti-foreigners, with particular emphasis in the definition of “foreigners” on the Irish, Italians, and Slavs, underpinned by a belief in the popular eugenics movement which viewed White Anglo-Saxons or “Teutonic” as the “superior” race.

Higham distinguished nativism and racism, although they could be closely related. Racism was (and is) concerned with hierarchical distinctions between racial categories, at the time predicated upon notions of “civilisation”, while nativism was primarily concerned with nationalist differences, i.e., a horizontal distinction between those belonging “to the nation, from outsiders who were in it but not of it.”1 The distinction could be drawn at the time due to differing strains of nativism, specifically those nativists who believed in the capacity of assimilation, holding that America’s assimilationist ability to incorporate the “huddled masses” was her greatest strength. To these nativists, controlling the pace and character of the new immigrants was desirable rather than wholesale restriction. A more explicitly racist form of nativism, however, sought not only to exclude immigrants but to continue to enforce differences in status within American society, e.g., slavery.

Three broad strands of nativism could thus be identified across the period from 1860–1925: the eugenic nativist racism of the New England Yankee patricians and their Teutonic “pure blood” ideals; the anti-Catholic nativism of the Protestants of the East and Midwest, sceptical of Irish, Italian, and Slavic immigrants but not opposed to German and Scandinavian Protestant immigrants; and, the anti-radical nativism of the capitalist elites and business owners, which viewed the waves of immigrants as “shock troops of class warfare, European style.”2 What unified all three strands of nativism in Higham's taxonomy was nationalism:

“Here was the ideological core of nativism in every form. Whether the nativist was a workingman or a Protestant evangelist, a southern conservative or a northern reformer, he stood for a certain kind of nationalism. He believed – whether he was trembling at a Catholic menace to American liberty, fearing an invasion of pauper labor... that some influence originating abroad threatened the very life of the nation from within.”3

The nativist movement found its first political expression in the American Party, known more commonly as the “Know-Nothing” party (reflecting the requirement that members deny knowing anything of nativist organisations), which viewed the influx of German and Irish immigrants as a “foreign invasion” and advocated for immigration restrictions and naturalisation requirements. While the Know-Nothing party ultimately fragmented between its abolitionist and pro-slavery factions and did not survive the Civil War as a political party, the perceived threat of the “foreign invasion” remained acute in the post-war period and the nativist movement it represented persisted in the form of numerous open and secret nativist societies.

The salience of the “varieties of nativism” Higham identified ebbed and flowed throughout this period. Anti-Catholic sentiment was particularly acute given the demographics of the immigrants relative to the perception of the East Coast blue-blood Yankees of America as an Anglo-Saxon Protestant nation. Protestant nativists viewed Catholic immigrants as the shadowy and insidious force of “Popery” seeking to flood the nation with Catholics loyal to Rome rather than to Uncle Sam, undermining the Anglo-Saxon character of America. The acute fear of a Papist revolution brewing in their midst was heightened by the political prominence achieved by Irish immigrants through the Democratic Party, which cemented the Democrats as the primary political opposition to immigration restriction. The threat was commonly depicted in popular culture as Irish immigrants in the form of unruly ape-like caricatures. The satirist Thomas Nast, a vitriolic anti-Catholic, published the cartoon below in Harper’s Weekly in 1870, in which the “simian Paddy” is “carving up the Democratic Party” as a fanatical-looking priest looks on.4

Virulent anti-Catholicism blended seamlessly with racist nativism, the latter of which was centred around the popular concept of “Anglo-Saxon virtue” in which race and religion were combined by America’s old Protestant elites, drawing both on 19th-century Romanticist desires to find the roots of a people and their nation in the foggy mists of time (hence the emphasis on “Teutonics”) and the 19th Century eugenics movement of “scientific racism”. In this nativist construct, America’s patrician Protestants traced their racial superiority to the Anglo-Saxons of medieval Britain and imbued them with specific virtues: an innate desire for political freedoms and liberty, superior intellect and physical attributes, and a unique capacity for self-governance (that justified the imposition of such rule of those considered so incapable). In this regard, Irish Catholics and, in the later 1880s and 1890s, Slavs and Italians, were viewed as inherently unsuited to self-governance, racially inferior, and innately attracted to despotism and tyranny.

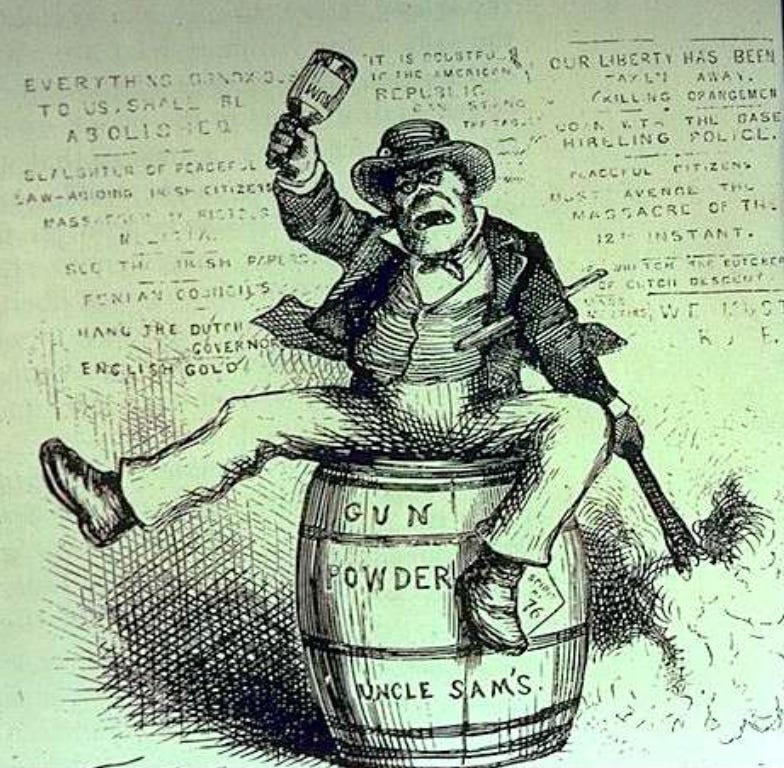

The supposed predilections of these new European immigrants for tyranny evinced the third but critical strand of nativism in its varieties, which was the fear of radical politics being imported from class-ridden and oppressed Europe. American nativists viewed Europe as the land of violent revolution and radical political ideas, heightened by the deliberate use of violence by the Irish Republican Brotherhood or “Fenian’ movement and the proliferation of the radical anarchist political movement on the Continent. Another Harper’s Weekly cartoon by Nast depicts an ape-like Fenian, drunk, sitting on gunpowder with a lit torch and a list of grievances scrolled on the wall behind; it appears to imply that the Irish ape is too drunk to notice he’ll blow himself up in the process of his drunken attempt to rectify his grievances. Anti-radicalism found a home among capitalist elites and business owners, who viewed the importation of class struggles as a threat to American businesses, which at the time held all the power against labour. Anti-radicalism thus appeared in its nativist form as a nationalist expression of “American values” and political and economic radicalism portrayed as profoundly “unAmerican”.

It must be noted, however, that while nativism remained present, it was far from a dominant force in American cultural and political life throughout this period. Not only were powerful forces mobilised against nativism at various times, but economic forces and certain ideas of America also mobilised socially and culturally against the salience of the nativists. The forces underpinning these fluctuations deserve some thought.

Fluctuations in the Salience of Nativism

The so-called “Age of Confidence” in the post-Civil War period up to the 1880s was characterised by a powerful emergent narrative of America, epitomised by the quote of Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes: “We are the Romans of the modern world, the great assimilating people.” Higham described American nationalism in this period as “complacent and cosmopolitan”, reflecting a relaxed and confident national mood that exalted the nation’s capacity for assimilating the mass waves of new European immigrants. This more optimistic version of nationalism defined the true strength of America by its assimilationist capacities, which conquered the nativist cries for a more exclusionary definition of “American” in this period.

This cosmopolitan and optimistic version of nationalism was buttressed by America’s geographic isolation and missionary sense of self as a nation of refuge, culminating in the dominant national mood that saw the new immigrants as fundamental to, rather than incompatible with, being “American”. The Age of Confidence assumed that America’s nationality and sense of nationhood were mixed; the expression of national characteristics and habits of the “Old World” homeland was not viewed as threatening to the understanding of Americanism, and the assimilation of multiple peoples into a distinctly American identity provided the nation with unique qualities. In this period, for example, sections of cities like Chicago and others in the Midwest had German language social clubs and schools. Such expressions of national identity were common, whether from Poles, Hungarians, Irish, or Italian immigrants.

Fundamental to this conception of the nation was the perception of America as a land of individual social mobility, in contrast to the hereditary class-based oppression of Europe; the Age of Confidence was underpinned by rapid economic expansion and prosperity, providing material reality to the “American Dream”. Foreign-born immigrants were not considered incompatible with nationalism because the very conception of nationalism situated foreigners as intrinsic to the nation’s sense of self. The new immigrants may have exhibited some strange tongues and stranger customs, but they were leaving the social ills of the Old World behind and forging a new path and a new life of individual liberty and mobility in the New World.

However, this “complacent and cosmopolitan” national mood in the Age of Confidence would buckle under the pressure of the combined scale of immigration and the economic crises of the 1880s. The immigrant influxes of the 1870s and early 1880s, combined with the economic depression of 1882–1885, heightened sensitivity to the apparent threat to domestic jobs posed by the new arrivals. Additionally, and importantly for the shifting salience of the three strands of nativism, from the 1880s to the 1890s, the “old immigrants” of Western and Northern Europe were gradually overtaken by the scale of arrivals of the “new immigrants” of Southern and Eastern Europe. For the ethnocentric racial strand of nativism, this was significant, as the nativists viewed the peoples of Eastern Europe as “educationally deficient, socially backwards, and bizarre in appearance”.5

The city slums and constellation of tongues could no longer be ignored, and nativists began to reclaim their voice, which the optimistic nationalism of the 1860s-1870s had drowned out. The nation’s ills began to be viewed through the prism of the new immigrants, particularly those concentrated in urban centres, who were linked to every social problem that America’s rapid economic expansion had brought, from urban squalor to labour unrest. Labour unrest provided a critical battleground in the 1880s as immigrant groups began organising and agitating for opportunity and better working conditions, squared against nativist labour organisations and the Yankee blue-blood capitalists who ran America's plutocratic, monopoly-based economy. Anti-immigration sentiment thus found widespread support among the "native" urban labouring class. Per Higham: “Nativism, as a significant force in modern America, dates from that labor [sic] upheaval.”6

The Age of Confidence in which immigration was conceived as a feature of the overall American national construct, the great assimilating colossus, thus gave way in the 1880s to the view of immigration as the problem in itself. To the resurgent nativists, it was the radical ideas in immigrant minds, the Papist religion in their hearts, and their distinctly “foreign” presence, that served to explain America’s social and economic travails. Nativist fears were exacerbated by events such as the Haymarket Square incident in 1886, in which anarchists in Chicago threw a bomb into a crowd of police during strikes for an eight-hour working day. Five German immigrants and one native American were sentenced to death, while the press descended into nativist, nationalist hysteria:

“The enemy forces are not American [but] rag-tag and bob-tail cutthroats of Beelzebub from the Rhine, the Danube and the Elbe... These people are not Americans, but the very scum and offal of Europe... a danger that threatens the destruction of our national edifice by the very erosion of its moral foundations.”

Throughout the 1880s, however, belief in the power of assimilation remained strong and nativist agitation, while finding groundswell in the economic recession of the mid-1880s, faced an uphill ideological battle regarding the role of the immigrants. Nevertheless, the nativist movement achieved some key initial milestones during this decade, in particular the 1882 passing of both the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended Chinese immigration for ten years and declared Chinese immigrants ineligible for naturalisation, and the Immigration Act of 1882, notable as the beginning of federal oversight over immigration control, which had previously been an exclusively state-level issue. However, the 1882 act was ambiguous and created uncertainty over the extent of federal authority over immigration.

At the state level, nativist sentiments found expression in attempts to legislate against “old world” expressions of national identity. In Illinois and Wisconsin, for example, where German was the language of instruction in many schools, legislation was proposed to enforce the conducting of all schooling in English. The 1880s were thus notable as a period of heightened nativist anxieties as the fear of German political anarchists, rebellious Irish Catholics and violent impassioned Italians loyal to Rome seeking to subvert America's Protestant character, and hordes of cheap Magyar and Slavic labour, converged into a heightened nationalism in the 1890s and early turn of the 20th Century. The answer, to the nativists, was simple; preserve “America for Americans”, with very specific definitions applied to the latter: White, Protestant, and Anglo-Saxon in “race”.

Thus, the political radicalism and Roman religion which comprised the dominant forces in the nativist movement through the 1870s and 1880s gave way in the 1890s to ethnocentric nativism as the fuel of the anti-immigrant fire. In the growing prominence of eugenicist theories in science, East Coast patrician intellectuals found a readily adaptable concept to apply to nativist sentiments, namely that America represented an Anglo-Saxon nation to which the peoples of Northern and Western Europe were suitable, but to which those from deeper into the Old World were inherently inferior. While this strand of nativism in the 1890s found itself confined to the intellectual blue-blood circles of the New England patrician class, their political power outweighed the reach of the ideas. Their legislative objectives included literacy tests, limiting the voting rights of unnaturalised immigrants, and federal deportation powers.

Politically, immigration restriction found a home in the Republican Party. The Democrats had attracted substantial support from foreign-born immigrants, and the Irish influx cemented the Democrats as a party that could not act as a vehicle for nativism. Legislative successes for the nativists were achieved with the passing of the Immigration Act of 1891, which provided clarity where the 1882 Act had failed by providing for exclusive federal control of immigration policy and establishing federal authority to deport immigrants who entered illegally. Steamship companies were obliged to return any passenger rejected at immigration depots. Literacy tests, while not included in the 1891 act, would become a major point of emphasis for the Anglo-Saxon ethnocentric nativists as a means of restricted immigration, particularly focused on Italians, Poles, and Hungarians.

Ironically, however, aspects of the Anglo-Saxon ethnocentric worldview would undermine the momentum of the nativist movement around the turn of the 20th Century, precipitated by America’s 1898 war with Spain in the Caribbean and the Philippines, which resulted in the U.S. acquiring the latter in the addition to Puerto Rico and Guam. The jingoistic elation which greeted this cementing of American hemispheric hegemony shifted the national mood to one of the “Great Civilising Mission” of America, superbly articulated by Higham:

“The imperialists' belief that the mighty impulse of the Anglo-Saxon race–now at the meridian of its strength–had driven America forth to conquer and redeem, expressed an exaltation transcending any fear of threat or dilution...If destiny called the Anglo-Saxon to regenerate men overseas, how could he fail to educate and discipline immigrant races at home? The newcomers, therefore, tended to figure among the lesser breeds whom the Anglo-Saxon was dedicated to uplift.”7

The early 20th Century was also characterised by increasing organisation and collaboration of the immigrants against immigration reforms. In 1907, the German-American Alliance and the Ancient Order of Hibernians came to a formal agreement to oppose all immigration restrictions. The Democratic Party, dominated by Irish Catholics which entailed a prominent role for the Catholic Church, championed the interests of fellow Southern and Eastern European Catholics. The rhetorical strategy of the immigration protectionists was, however, notable for its emphasis not on the characteristics of the immigrants themselves, but on a conception of a cosmopolitan America in which a distinctive nationality could be forged from the mixture of the huddled masses. This cleverly twisted the nativist’s portrayal of the immigrants as deficient and inferior, and positioned America as the force that would elevate and alleviate the newcomers, manipulating the concept of the “Great Civilising Mission” to the immigrants’ advantage.

Nevertheless, the resurgence of confidence in the conception of America as the great assimilating nation through the early part of the 20th Century floundered in the economic recession of 1913 and the outbreak of the First World War in Europe, which released frenzied anti-German sentiment. This posed a paradox given that German-Americans constituted the nation’s single biggest ethnic group, which found expression in a general antipathy against “hyphenated Americans”. Nativist anxieties thus shifted away from arriving immigrants per se, towards the “aliens” already in society, those born in America but harbouring allegiances to their home country and willing to subvert America from within. President Wilson’s decision to declare war on Germany and enter America into the war provided the vehicle for the expression of a new nationalism, the “100% Americanism” movement, which demanded unyielding national unity and patriotism.

The “100% Americanism” movement during the period between 1915 and 1920 was, however, a positive articulation of American identity, evidenced by the Fourth of July celebration’s temporary renaming “Americanisation Day” in 1915 under the slogan, “Many Peoples, But One Nation”. As the war progressed, the emphasis on demonstrating a commitment to being “100% American” found expression in codified processes and rituals of naturalisation for new U.S. citizens, under a slogan recognisable today: “America First”. By the early 1920s, however, the positive articulation of “100% Americanism” was superseded by a negative, defensive conception as isolationism gripped the nation. The isolationist spirit of the day found a willing accomplice in nativist doctrines of American identity, who viewed the foreign presence in the population as a threat to American stability.

Lobbying for immigration restriction and economic discrimination against foreign-born labour were resuscitated with vigour, culminating in the crowning achievement for the nativist movement: the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924. The 1921 Act introduced numerical limits on immigration for the first time, capping annual immigration from any country to 3% of people from that country already living in the U.S. at the time of the 1910 census. The 1924 Act, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, further restricted immigration annual immigration to 2% of the people from each nationality in the U.S. as recorded in the 1890 census and completely excluded Asian immigrants, Japanese in particular. The Johnson-Reed Act effectively brought to a close the era from the end of the Civil War characterised by mass immigration and nativism agitation.

Echoes in the Present Day

What allowed America to navigate the nativist challenge throughout that epoch was the strength of her economy, her democratic institutions, and her national sense of self and mission in the world. Economic prosperity dampened nativism as much as recessions aggravated nativist anxieties. Democratic institutions, including a genuinely free press active in holding power to account, strong civil society organisations, and a bipartisan Congress, curtailed nativist agitations for 60 years before the stringent immigration restrictions of the 1920s. And while differences in the conception of “America” existed throughout the period, there was an overarching sense of America’s role in the world, intimately connected to its conception as the land of liberty to which the oppressed peoples of the Old World might find a new life of social, political, and economic freedom.

In 2024, waves of Europe’s destitute “huddled masses” are no longer a primary concern for the United States; anti-immigrant rhetoric has shifted to Central and South America, but the core motifs of the 1860-1924 epoch remain. In a paper published in 2000, which would form the epilogue to the 2002 reprint of his seminal work, Higham encapsulated these motifs exquisitely:

“Now an acrid odor of the 1920s is again in the air. It rises from the vast fortunes accumulating around new technology; from a grasping individualism eroding traditional constraints on the market; from a reckless hedonism in popular culture and a resurgent religious conservatism mobilizing against it; from a profound distrust of the state, a reviving isolationism, a growing demand for immigration restriction, and a deadlock in race relations.”8

The “acrid odor of the 1920s” occurs, however, at a time when the factors that acted as counterforces against the surging nativist tides are no longer present; America’s democratic institutions are in tatters, the American economy, while currently experiencing strong growth, is a monopoly-driven plutocracy similar to the Robber Baron era, and America has experienced a profound loss of confidence in its national sense of self. For now, it appears that nativism is once again in the ascendancy.

However, if the Democrats are capable of some self-reflection (which is highly doubtful), they might find that coalitions of immigrant resistance to nativist hostility throughout the 1860-1924 era were grounded in positive and patriotic conceptions of America, not the cultural nihilism and moral narcissism that characterises the view that so many Democrats hold of America today. If Democrats spent less time making specious and ahistorical comparisons to European 20th Century fascism, they might find some salient lessons are there to be learned from their own history.

Higham J. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. Rutgers University Press: 2022.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Casey, D. 19th-Century Irish ‘Ape-Man’ Cartoons and the Aesthetic of the Grotesque. Doctoral Dissertation, Trinity College Dublin, 2015.

Higham, p.65.

Ibid., p.53.

Ibid. p.109.

Higham, J. Instead of a Sequel, or How I Lost My Subject. Reviews in American History. 2000;28(2):327-339.

Thanks a lot, Alan, for this one! Highly appreciate your history "lessons" - I wish a brilliant, detailed and astute Analysis like this essay of yours was used as exactly this, a "lesson" to learn from! However, wishful thinking, I am afraid.. I really enjoyed it nonetheless, brilliant read and food for thought 🙏🏻

Deep thoughts at 3am, read at 3.45am.