It seems that there isn’t a serious conversation for which social media is not capable of reducing to a mere caricature of itself. A vortex for the distillation of complex issues into a superficial sea of soundbites. And if anything currently epitomises this distortion of the important into the mundane, it is the conversation around mental health, for men in particular.

It is part of a culture for which being seen to take an issue seriously, to be the one appearing to “do the work” is the end in and of itself, superseding the veracity of the issue, which in this case is subsumed in a haze of empty mindfulness quotes. It speaks volumes about our culture that the rallying cry is always “raising awareness”, which can be performed from the couch just by reposting an MMA fighter's appeal to a very caricature of this issue: “see, tough guys talk about it too!”

Packaging mental health into something Instagrammable encourages elevating everyday fluctuations in mood to the level of “mental health”, while derogating the serious, dark side of this issue out of the conversation. “Self-care” becomes just another obsession with “self”, and the privileged post pretty pics of a boujee holiday wrapped up as a “mental health break”. Love, you’re in Ibiza. And because it is reduced to its lowest common denominator, everyone on social media has, apparently, “depression”. Or at least they’ve decided the label is something worth claiming in a culture where, when it comes to mental health issues, self-diagnosis is now the accepted norm. In an excoriating article critiquing the book ‘Obsessive, Intrusive, Magical Thinking’ by Marianne Eloise and the book's celebration of mental health issues under the opaque term “neurodivergence”, Freddie de Boer wrote:

“There was a time when self-diagnosis was understood to be unhealthy, and perhaps embarrassing, but this is a brave new world we’re living in now...Once enough people insist on mental illnesses as upbeat and fashionable lifestyle brands, then any of us who oppose it are guilty of the most grave sin of all, the sin of perpetuating stigma....Stigma, that cartoon monster, has never been in the top 100 of my problems in 20 years of managing a psychotic disorder, but never mind; stigma is the ox to be gored in contemporary pop culture, and so we must fixate on it to the point that we sideline the health, safety and treatment of those with mental disorders.”

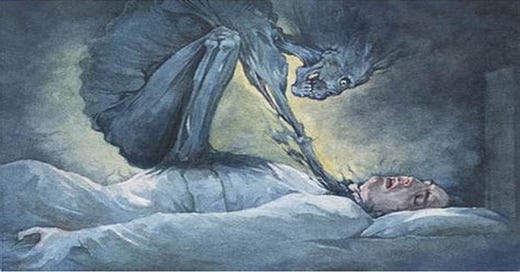

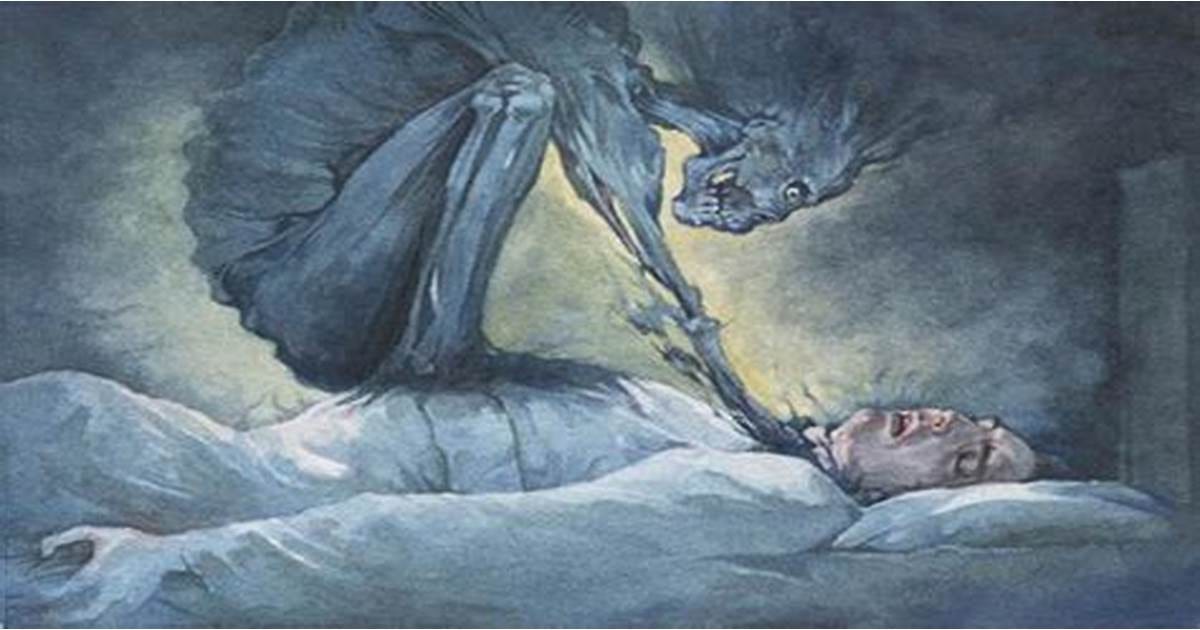

This highlights one of the bizarre dichotomies of the mental health conversation, which exists in a culture that now glorifies “neurodivergence”, but uses that umbrella to coopt real mental health issues and cognitive disorders as something to celebrate, while still expecting an urgent and consequential conversation around issues like male suicide. It is the mental health equivalent of cakeism. This isn’t a culture in which there is a stigma around mental health issues; it’s a culture where there is a stigma around being ordinary, of being just another person, and the “mental health” moniker allows us all to be special. Did you ever think for people who really struggle, Instagrammable mental health superficiality may have the opposite effect than encouraging “just talk about it”? Demons are diminished in their real power by the belittling effects of our pop culture mental health porn.

This culture tips the balance of the discourse disproportionately to the person who can't differentiate between a bad morning and “being depressed”, and sidelines those with either an actual diagnosis or more serious struggles with depression. It devalues the need for professional expertise, as if these issues are all solved over a good cry on the shoulder with the lads. Now, everyone is a psychologist with a cute quote and a sunset photograph.

And this culture is also an entitled one, one that expects any discussion on the issue to be qualified with the mental health “positionality” of whoever is talking. You’re doing it right now, waiting for me to qualify this entire essay with some labels about myself to validate any of the critiques. And that is telling in and of itself, because you feel entitled to know my struggling, without which I lack your validation. And I’m not giving you that satisfaction, because that would both make this essay about me and succumb to the game of mental health voyeurism.

Grossly oversimplified caricatures like “men just need to talk” in fact trivialise the complexity of both drivers and remedies, even assuming there is one of the latter available. But some men have done the talking, and they still want out. And that fact is what no one can admit in this conversation, because human mortality salience and terror of death activates a shift to making the conversation about the person “raising awareness”, not the person who may have exhausted all avenues and just wanted the fuck out of this world. It also makes an assumption that such a person owes it to you to exhaust all avenues. But no one owes you their presence in the world if to exist in it brings nothing but mental anguish. No one owes you their presence in the world full stop.

Ultimately, the whole conversation makes a mockery of the solemn dignity of just suffering and putting one foot in front of the other, day after day. To come back to de Boer on this very issue, in words that spoke straight to my thoughts on this issue:

“Eloise and people like her seem never to consider one of the possible ways that they could have dealt with their myriad disorders: to suffer. Only to suffer. To suffer, and to feel no pressure to make suffering an identity, to not feel compelled to wrap suffering up in an Instagram-friendly manner. To accept that there is no sense in which her pain makes her deeper or more real or more beautiful than others, that in fact the pain of mental illness reliably makes us more selfish, more self-pitying, more destructive, and more pathetic. To understand that and to accept it and to quietly go about life trying to maintain peace and dignity is, I think, the best possible path for those with mental illness to walk.”

I think that is the path I'd rather walk, to find purpose in the struggle, and meaning in silent dignity.

Social media would have us all become Marianne Dashwood, for whom the only proof of deep feeling is in its display.

Excellent essay!

"Demons are diminished in their real power by the belittling effects of our pop culture mental health porn." Yes, I really hate how very often on social media it is portrayed like mental illness would add something to you. If it does fine, but chances are very low in reality. If anything it takes away from the finer sides of being human.