Can the Islamic Republic Fall?

As it stands, the counter-revolution cannot topple the regime alone.

As the Islamic Republic’s brutal monopoly on violence runs unchecked in Iran, and death toll estimates range from 3,000 to 20,000, much of the commentariat in the West has filtered this moment through a predictable lens, reducing the discourse to a morality play judged not by reference to any discernible principle, but relative to who the actors, or perceived actors, happen to be. The fundamental principle that a government is slaughtering its people is relegated to secondary consideration.

You do not need to know anything else about the history of Iran, of the Islamic Revolution, or of the meddling of foreign powers in Iran over the past century, whether Russia in the early 20th century or the U.S. and Britain during and after the Second World War. None of these antecedents necessarily matter for this moment because, if you believe in basic human freedoms, rights, and dignity, a government of any ideological persuasion massacring its own people is exactly what it is.

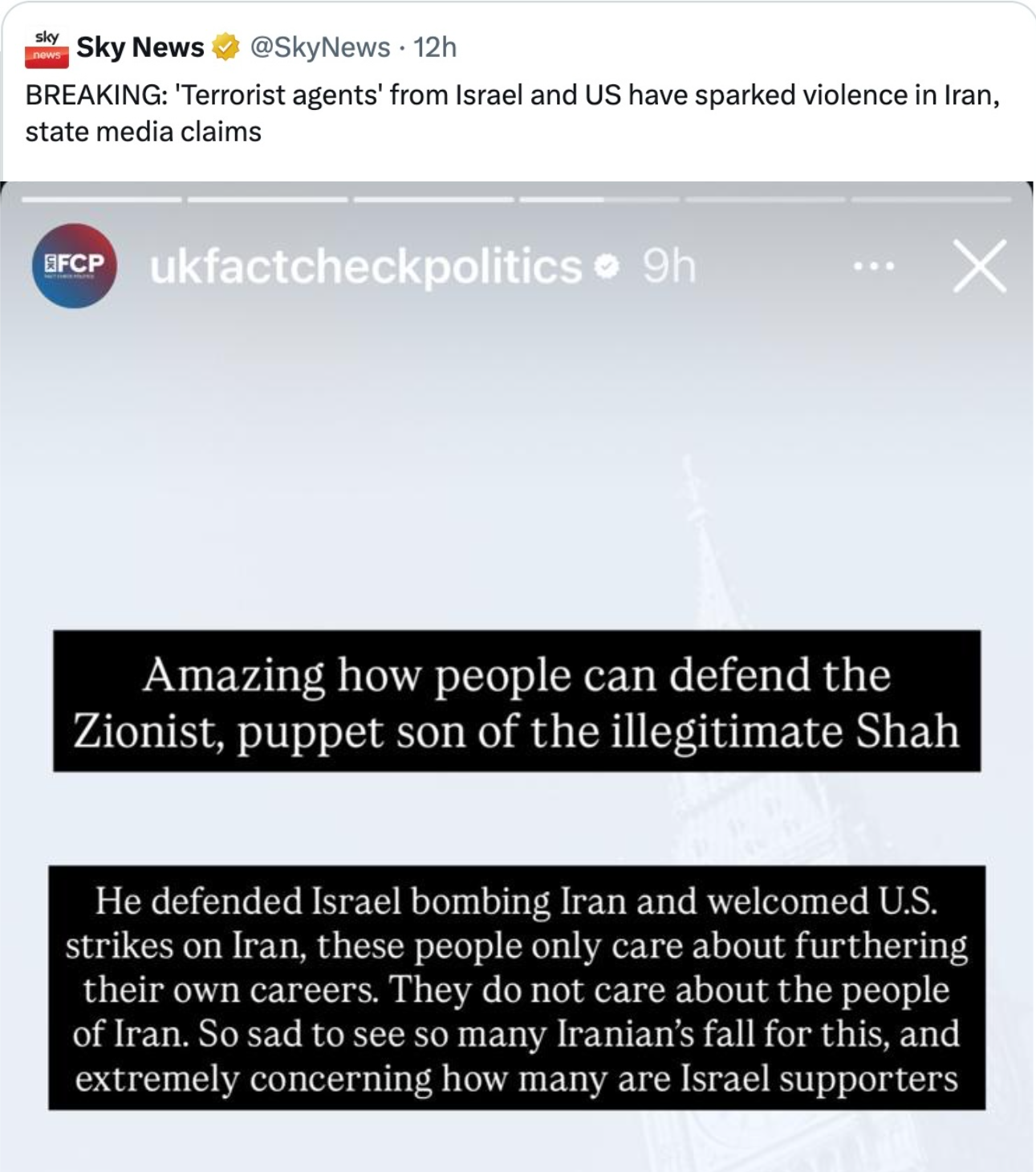

And yet the reflexive response of so much of the Western liberal information ecosystem has been to delegitimise the counter-revolution by inserting their own neuroses regarding Israel, America, and the West, into the situation. This “Just Asking Questions” fallacy strips the Iranian people of their agency in this moment, framing this counter-revolution as a result of “Zionist” or American agitation, with Sky News parroting the regime’s party line without hesitation, or, as UK “Fact Check” Politics put it (an ironic title if ever there was one), a desire to get a “Zionist puppet” in Reza Pahlavi back in power. If you needed to understand the “anti-imperialism” of idiots in action, this is it.

In fact, re-reading Leila Al-Sharma’s essay on the “anti-imperialism” of idiots while writing the previous 3am Thoughts, I was struck by how analogous the issues she described in her piece during the Syrian Civil War are to the current counter-revolution against the Islamic regime in Iran.

“Hundreds of Syrians are being killed every week in the most barbaric ways imaginable. Extremist groups and ideologies are thriving in the chaos wrought by the state… There’s no major people’s movement which stands in solidarity with the victims. They are instead slandered, their suffering is mocked or denied, and their voices either absent from discussions or questioned by people far away, who know nothing of Syria, revolution or war, and who arrogantly believe they know what is best. It is this desperate situation which causes many Syrians to welcome the US, UK and France’s action and who now see foreign intervention as their only hope, despite the risks they know it entails.”

In the past week on social media, I’ve seen the suffering and murder of Iranian people mocked and slandered, framed as Israeli propaganda or exaggerated claims by the Iranian diaspora, all tinged with the usual performative cruelty from the West's self-annointed moral avant-garde, for whom their self-styled humanitarianism is always conditional, qualified by who exactly they deem worthy of the benevolent cloak of their self-righteousness, or not. These are not moral actors; they are moral vultures feeding on the pain and suffering of other people.

Comfortable comment-section-bottom-feeders, the very people who, for two years, questioned nothing coming out of Gaza, suddenly question the voices and motives of those in Iran and in the diaspora. Perhaps more than anything, it is tragically clear how far too many people would rather see the Islamic Republic remain and, whether they say this quiet part out loud or not, see Iranians slaughtered by their government, than Israel or America have any hand in aiding the protestors in bringing down the regime. It takes a particular form of moral narcissism, a distant moral indulgence, to view the suffering and death of the Iranian people under brutal theocracy through one’s own sense of self-righteousness, irrespective of the consequences for the people in question. To quote Leila Al-Sharma:

“There are many valid reasons for opposing external military intervention in Syria, whether it be by the US, Russia, Iran or Turkey. None of these states are acting in the interests of the Syrian people, democracy or human rights. They act solely in their own interests… Yet in opposing foreign intervention, one needs to come up with an alternative to protect Syrians from slaughter. It’s morally objectionable to say the least to expect Syrians to just shut up and die to protect the higher principle of ‘anti-imperialism’.

It is this last point that I would like to work through today. I won’t pretend to have an answer to this question, either, as I’m conflicted between the obvious need for some factors to address the power imbalance between the regime and the protesters, and the realities of what overthrowing the regime entails. This question of foreign intervention has already been reduced to sloganeering and moral grandstanding, so let’s try to render a sober assessment.

The first thing to consider is the nature of the Islamic regime in Iran itself, structurally, which is relevant to whether any popular uprising could bring down the regime on its own. The second is to consider what factors historically tip the balance in favour of such popular uprisings. The third is to consider, having regard to those preceding factors, the balance lies in favour or against some intervention (not only considering the U.S. here, but anyone).

The Nature of the Regime

Let’s start with the nature of the regime, which the political scholar Mohammad Tabaar described in a 2021 paper as “too rigid to bend and too ruthless to break.” One reason for this description lies in the particular structure of the regime, known as “the parallel state”, reflecting the positioning of the state institutions between the elected government headed by the president, and the Islamist clerical theocracy headed by the “supreme leader”, i.e., an Islamist cleric. In this structure, the institutions of Islamist theocracy sit “parallel” to the government, responsible for implementing Islamic law over society. This structure means that any hope for reform, particularly less stringent enforcement of Islamism over society, is vested entirely in the government and the office of the president. Over the past three decades, the presidency has been the aspiration for reformers and modernising political movements within Iran.

The parallel state is crucial to understanding the current moment in Iran. Waves of civil unrest have flashed in recent years; 1999 student protests at Tehran University; the 2009 Green Movement protests against the rigged “reelection” of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; 2017, 2019, 2020, and 2021 in response to economic conditions; additional 2020 protests against the shooting down of the Ukrainian Airlines flight 752 by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC); 2022 in response to Mahsa Amini’s murder. While violence and repression were deployed by the regime at times, notably during the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests, the regime often dealt with these waves of protests by the president and government stepping forward with promises of reform. Such promises of reform were lapped up by a gullible Western media, eager to endorse “the reformers”. Yet true reform never came, because one lesson the clerical theocracy internalised from the fall of the Soviet Union is that reform is the slippery slope to termination.

The reason the present moment represents more than mere protest, but a fully fledged counter-revolution seeking the overthrow of the regime, is that the Iranian people have also internalised their own lesson: that reform isn’t coming. That despite the structures of the parallel state, no reformist president is coming to save the day; that the clerical theocracy is the primary institution of the regime. That the raison d’être of the Islamic Republic is continued, perpetual Islamist revolution, “axis of resistance”, “death to America”, and “death to Israel”, not “long live Iran” or any positive vision for its people. That the regime has no conception of nationhood beyond its own crippling theocratic doctrines; that the regime is willing to expend billions to export terrorism and fund its proxy militias to achieve “death to Israel”, while crippling the economy of the nation. This is why one of the main slogans of Iranian opposition movements is “Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, My Life for Iran”.

However, a regime that views internal reform as the seeds of its own destruction, while being infused with the death-soaked doctrines of Islamism, presents an entirely difficult calculus to other popular movements that have resulted in regime change, such as the 2022 “Aragalaya” movement in Sri Lanka, which forced the resignation of the ruling elite’s president and prime minister (who are brothers). For the Islamic Republic, however, whose self-conception is permanent religiously-sanctified revolution, there are absolutely zero moral limits on ensuring its own survival. It will slaughter, and is slaughtering, as many of its own people as required for the regime to survive, because to the clerics, it is God’s will. If a regime has no limits on the suffering it will inflict to survive, but the regime’s opposition does have such limits, this creates a profound asymmetry in favour of the regime. It can, and will, just keep killing, and killing, until the opposition reaches its limit and falters.

One of the challenges of the Islamist totalitarian doctrines that define the regime is that no amount of failure is enough, because failure can always be framed as merely a signal to continue on God’s path, that redemption is always on the horizon and merely requires more pain and perseverance to attain. And the Islamic Republic is simply one perpetual failure; an economic ruin, a geopolitical ruin, a humanitarian ruin. Its empire of rubble across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Gaza, and over its own people, is a macabre catastrophe of human suffering. Other than having zero moral limits on ensuring its own survival, what makes such a failed regime as the Islamic Republic endure? In their book, Revolution and Dictatorship, the political scientists Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way identified three characteristics of durable dictatorships:

A cohesive ruling elite;

A loyal and powerful coercive security apparatus;

Weak and divided opposition.

The Islamic Republic is, unfortunately, a prime example of the first two characteristics. The clerical theocracy, headed by the Ayatollah, provides a cohesive ruling elite that has never exhibited much internal disloyalty or potential for a challenge to the regime to emerge from the elite. And when certain reformist candidates were running for election in the context of recent civil unrest, the 12-member clerical body that approves parliamentary and presidential candidates, known as the Guardian Council, began to exercise more direct control, intervening to disqualify reformist and centrist candidates from standing for parliamentary elections, resulting in a default overwhelming dominance of conservatives in government. The Islamic Republic has constantly cemented the cohesion of its ruling elite, not only understood through the prism of theocratic religious revolution, but by framing the entire existence of the regime as against external enemies. The Iraq War cemented this initial cohesion between theocracy and military, and the rhetoric of the “Great Satan” (America) and “Little Satan” (Israel) has served as an ongoing source of unity for the ruling elite, framed as a constant existential struggle.

At its disposal, evident in the tragic slaughter currently taking place on the streets of Iranian towns and cities, is a powerful, repressive security apparatus loyal to the ruling elite. The IRGC and the intelligence services, their Basij paramilitaries, and the police, including the so-called “morality police”, constitute a formidable network of coercive state repression with overwhelming capacity for inflicting violence on the civilian populace at the behest of, and for the survival of, the ruling elite. The fact that there are now reports of Kataib Hezbollah and other Shia militias from Iraq being brought in to bolster the regime adds another layer to this coercive apparatus, as the regime can draw on its empire-by-proxy to ensure its survival. The integration of the coercive apparatus of the state’s military and police with the interests of the theocratic ruling elite provides the glue that makes the Islamic Republic “too ruthless to break.”

These factors become formidable when the opposition is weak and divided. Due to the increasing exercise of control over the clerical theocracy over the government, political opposition in the Islamic Republic has been managed and prevented from mobilising by the regime. Moreover, the nature of popular civil protest movements, as described earlier, has historically been based on desires for reform. That moment is over; the present uprising represents a fundamental shift in the nature and unity of Iranian opposition. This is being expressed, on the streets of Iran and the protests in Western capitals, by chanting for Reza Pahlavi, the son of the last Shah, not because people necessarily wish for a return of a ruling monarchy, but because he represents a visible, recognisable, unifying symbol of opposition to the Islamic regime. He represents the day after the fall of the Islamic Republic. Iranians of all opposition stripes are now united with one sole end in mind: the overthrow of the regime. What comes next, whether a secular parliamentary democracy or a constitutional monarchy with sovereignty vested in parliament, is a decision for the Iranian people to take when the regime is ousted.

One aspect of all of this which seems difficult for much of the Western commentariat to grasp is that Iran is not an Arab country. Yet, it is treated as if the dynamics and characteristics are interchangeable with any other Arab country in the Middle East. For starters, Iran is much more ethnically diverse than the homogenous Arab states. This is particularly important in the context of the relationship between religion and national identity. In the Arab world, Islam is totalising; it is both faith and identity, and Islam is indivisible from Arab identity. The Islamic conquests through the Middle East, North Africa, and into Spain over the 7-9th centuries represented the Arabisation and colonisation of what had previously been a diverse array of peoples and cultures. In almost all of this region, those peoples were subsumed into Arabisation. Surviving minority groups in Arab countries, such as the Kurds, Druze, or Copts, have always been subjugated to the totalising Arab-Islamic colonial project. In Persia, the attempt at Arabisation prompted a unifying of Persian and other regional ethnic groups disgruntled at the Caliphate’s rule, leading to the Iranian Intermezzo, or “Persian Renaissance”, which ended Arab rule over Iran and restored Persian control over their lands, revived the Persian language, and saw the emergence of distinct Iranian identity that retained Islam, but was not defined by it, and in which several ethnic groups other than Persians, including Azeris, Kurds, other Turkic groups, found a unifying Iranian identity.

Four important factors for the present moment emerge from this history. The first is that there is a deep sense of Iranian national identity that is entirely separate and distinct from Islam. The second is that Iranians are far less Muslim than the regime’s existence and propaganda convey, with almost as many Iranians identifying as ‘None’ or ‘Atheist’ as those identifying as Shi’ite Muslims. The third is that, despite the regime’s “death to Israel” rallying cry, most Persians possess none of the enmity towards Jews that so animates their Arab neighbours. The final factor is that in the context of regime change, Iranians have a history of fighting for parliamentary representative democracy, stretching back to the Constitutional Revolution of 1905.1 Hence, as stated earlier, this moment in Iran is in fact a counter-revolution against the Islamic Revolution; against Islam and religiosity itself, expressed as secular Iranian nationalism, pride in Iranian identity that is independent of Islam and the regime that oppresses, tortures, and kills in the name of Islam. This nationalist Iranian Revolution constitutes a counter-revolution to the Islamic Revolution. And this movement is not about “reform”; it is about regime change.

The Nature of Authoritarian Regime Change

While there is now strong opposition within Iran to the Islamic regime that goes beyond demands for mere reform, the reality of a cohesive ruling elite and control of coercive security apparatus remains a formidable challenge. Judging by much of the online discourse, it seems many in the West will only be happy if the Iranian protestors overthrow the regime with their bare hands.

In the history of how authoritarian regimes fall, except through total unconditional destruction (e.g., Germany and Japan in the Second World War), perhaps the most crucial element is the domestic military and security apparatus. A ruling elite may be present, but if a strong independent military exists that is not entirely in the pockets of the ruling regime, it may act as kingmaker, as has occurred in Pakistan in 1957, 1977, and 1999. Egypt also provides a good example of the military acting to depose a government, in which capacity it acted with Hosni Mubarak during the Arab Spring in 2011, and then just two years later, in 2013, overthrew Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood and pursued a major crackdown of the Brotherhood in Egypt.

An example of the military and security apparatus standing down, rather than directly orchestrating regime change, is the “Bulldozer Revolution” mass protests in Serbia in 2000 that led to Slobodan Milošević’s overthrow. Ordered to use force against the civilian protesters who descended on Belgrade to storm the parliament and state TV buildings, Serbian military commanders refused their orders and stood down their troops. There were also mass defections from the military and police, many joining to support the protesters. By showing that Milošević’s ruling regime no longer had the backing of the military and police, the regime lost its power to enforce its rule and collapsed. The role of the military and security apparatus is therefore the crucial operative mechanism for any successful domestic revolution, whether defecting from the ruling elite to support a civil uprising, or standing by while a popular mass uprising unfolds.

As things stand in Iran, there is no evidence of this occurring. The military and security apparatus remain on the side of the regime, slaughtering their own civilians with impunity. And for those seemingly opposed to “foreign intervention”, that is already occurring at the behest of the regime in the form of Iraqi Shia militias. There have been reports of Kurdish fighters attempting to cross into Iran, but Turkish intelligence, ever motivated by the Turks’ hatred of Kurds and support for Islamist terrorist regimes, warned the IRGC of this development. So the “foreign interference” that is now apparently a principled stand to take against among the Western activist class applies only to Israel or the U.S. How predictable. There is an urgent necessity for some counterbalancing use of force against the regime, which the protestors do not possess alone. Without any counterbalancing force, without elements of the IRGC deciding the Ayatollah has had his day, or military commanders refusing orders, the protestors simply do not have the leverage to overthrow the regime.

Is that enough of an argument for Israeli and/or American intervention?

A Helping Hand to Overthrow the Regime?

And so we circle back to Leila Al-Sharma’s moral clarity; that while there may be valid reasons to oppose foreign intervention, anyone doing so better have some cogent alternative to how people in Iran free themselves from the Islamic regime. So far, I have heard little by way of principled, reasoned objection to foreign intervention; only the psychodrama relativist irrationality of the Tankie corners of the Western Left and the Free Palestine crowd, whose pathological hate of Israel is boundless, and upon the altar of which hate they are more than comfortable with thousands of Iranians dying in the name of their “anti-colonial liberation” movement. There is certainly no objection to Iraqi militias or Turkish intervention to help the most tyrannical dictatorship outside of North Korea survive. Iran has, once again after the Mahsa Amini protests, revealed the moral incoherence of the Western activist class and the regressive ideological convictions of the Free Palestine movement.

The case for intervention is plain; without external forces to shift the power imbalance between the protestors and the regime’s security apparatus, the regime’s monopoly on violence will slaughter the protestors until the momentum of the counter-revolution is sapped and the clerical theocracy remains. However, the calculus for intervention, the how and what of any such intervention, is more complex and warrants serious thought. For starters, what aspects of the regime infrastructure should be targeted, i.e., what is the primary objective to achieve in any intervention? Secondly, what contingencies require consideration to ensure that any such intervention results in a stable post-regime Iran? This is particularly important in a nation which, although now the protestors are openly calling for Trump to intervene, is also a proud nation deeply suspicious of meddling foreign powers, even before the Islamic Republic. As such, any intervention needs to consider the potential for a “rally around the flag” moment.

In relation to the first question, given the nature of durable authoritarian regimes outlined earlier, the primary objective should be to target the regime’s senior clerical and military leadership, and IRGC military targets and infrastructure. Israel and the U.S. have already demonstrated the ability to isolate and target regime personnel; what would be required here is the same precision, only to a far greater extent than the limited targeting of, e.g., the nuclear programme. Severing the chain of command between the security apparatus and the boots on the ground might help tip enough rank-and-file troops and police towards the protestors, and persuade some mid-level commanders with a mind toward their future to similarly defect or, at least, withdraw their support from the ruling clerical elite. Ultimately, the objective is to severely damage the capacity of the IRGC to suppress the protestors and remove their monopoly on violence, and to force the clerics to realise that the game is up. Yet could such strikes result in a “rally around the flag” moment? The 12-Day War with Israel last June suggests not, as the Iranian opposition hoped it might result in the regime collapsing. The Iranian opposition in Iran and in the diaspora is openly calling for help. The questions over who should help are viewed for what they are: the luxury moralising of people who will not bear the consequences of their views. Nevertheless, the optics of any intervention will be important, and the defining images of the regime’s collapse need to be Iranian protestors swarming the Office of the Supreme Leader, not American jets over Tehran.

The second question is where there have been some understandable and thoughtful hesitations, particularly given America’s recent history of attempted regime change in Iraq and Afghanistan, or other air support military interventions by Western powers, such as Libya. However, these are not quite appropriate comparisons. In the first instance, Iraq and Afghanistan entailed full-scale American invasions and occupations to attempt to force regime change. There is no suggestion of U.S. troops deploying to Iran, and post-regime Iran is not being left to clueless Americans stepping into a power vacuum as if it were merely an administrative task, as in Iraq and Afghanistan, or creating a power vacuum and flying off, like in Libya. Neither Iraq, Afghanistan, nor Libya provide useful comparisons for a society like Iran, which has an educated population and a strong diaspora, with democracy and policy networks and think tanks all highly engaged with shaping a post-regime Iran. Rather, the biggest threat to a post-regime Iran is the current structures of the regime. In particular, the IRGC could decide the mullahs’ time is up, but move to consolidate their own power as the new ruling elite. In this scenario, Iran transitions from a clerical theocracy to a secular autocracy.

This latter threat entails perhaps an additional element in the calculus, at least for Israel; the impetus to critically incapacitate the IRGC from being able to wield such influence should the mullahs abdicate. States act out of their own self-interest, and Israel’s paramount self-interest is its security. And as the regional response to Iran’s attacks on Israel illustrated, in which Jordan, the Saudis, Bahrain, and the UAE, all assisted with either direct intervention or intelligence sharing, enough Middle Eastern states view Iran as the primary threat to regional stability. Since October 7th, the actions of Hamas from Gaza, Hezbollah from Lebanon, and the Houthis from Yemen represented a careful cultivation of empire-by-proxy that sought to shift the balance of power in the Middle East towards Iran’s brand of militarised pan-Islamism. As Hamas is now crippled in Gaza, Hezbollah defanged in Lebanon, and the Islamic Republic’s nuclear programme damaged, the present moment presents an opportunity for the regime, as the major supporter of terrorism in the region (other than Qatar), to be dealt a deathblow.

Given the scale of slaughter already unleashed by the regime on its own people, it is morally unconscionable to insist that Iranians die with no hope of ridding themselves of this 47-year nightmare of Islamist hell. Is there a form of pure revolution that would please our moral avant-garde in the West? Oh, of course…that was the Islamic Revolution itself. The Islamic regime in Iran has never been weaker. But it is clear that the regime won’t fall without some help. The Iranian opposition is calling for that help. I find it hard to justify ignoring that call. I hope any intervention is enough for the regime to fall, and for Iranians to reclaim their country and their future.

Conscious that I’m referring to several historical events in passing, I’m writing a deeper piece on the historical events that shaped Iran over the last century, to follow this. The intention will be to get away from the “CIA-overthrew-democracy = Shah-bad-man = Islamic Revolution” narrative that plagues most dialogue about Iran.

Really nuanced take on an impossible situation. Your breakdown of the parallel state makes alot of sense for why reform never worked. When I studied comparative regimes in gradschool, the three characteristics you cite were always key. The moral question is tough tho when the opposition is openly asking for help but critics expect them to overthrow a brutal theocracy barehanded.

In akharin nabarde…